By Beth Deitchman

It was a little more than two years ago when composer John Debney began work on the stirring score for The Jungle Book, now captivating audiences in theaters all around the world. But that’s hardly the “Once upon a time…” in Debney’s Disney story, which begins—like so many of our favorite Disney stories—with none other than Walt Disney himself. John sat down recently with D23 and shared his memories of growing up on the Disney Studio lot, of being mentored by Disney Legends Richard M. Sherman and Buddy Baker, and of landing his dream gig—scoring the live-action re-imagining of The Jungle Book.

Chapter One—Growing Up Disney

It was during the Great Depression when 12-year-old Lou Debney began selling newspapers on a Los Angeles corner, to help his family make ends meet. That corner was none other than Prospect and Hyperion—and over the three years that Lou Debney sold papers at that corner, he developed a friendly rapport with one of his regular customers: Walt Disney. According to John Debney, “Around the time that he was probably 15 or 16, he started asking “Mr. Disney” almost daily—without bugging him too much—‘I’d really love a job someday if you have anything ever.’”

And one day in 1936, Walt, who had taken a liking to Lou, told him that they were planning to move to a bigger place on Hyperion Avenue. “Why don’t you come over and fill out the paperwork?” Walt said to Debney’s father. Before long, Lou Debney was carrying a Studio ID card—No. 177—and was working as the “clapper boy” on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. This marked the beginning of a 45-year Disney career for Lou Debney, who worked for the Studio in a variety of capacities. His credits include assistant director on a number of animated shorts, like How to Play Baseball and Goofy’s Glider, associate producer on Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, and production coordinator on the TV series Zorro.

Remembering his father, John Debney says, “He was one of those quintessential do-it guys, and I think Walt gave my dad a lot of things to do, just because he was sort of a ‘can-do’ person. And he hung around for all those years and was a pretty integral part of the Studio for many years.”

And the Studio became a part of Debney family life for many years, too. On weekends, Debney would accompany his dad to the lot, which was relatively deserted on Saturdays and Sundays, and he can remember seeing the Burbank lot from atop Lou’s shoulders. Debney also remembers frequently running into Walt during those visits. “Walt would be there many, many weekends,” he recalls, “kind of looking around and poking in the animators’ rooms when they weren’t there, seeing what they were doing, and checking their progress. We would bump into Walt often.”

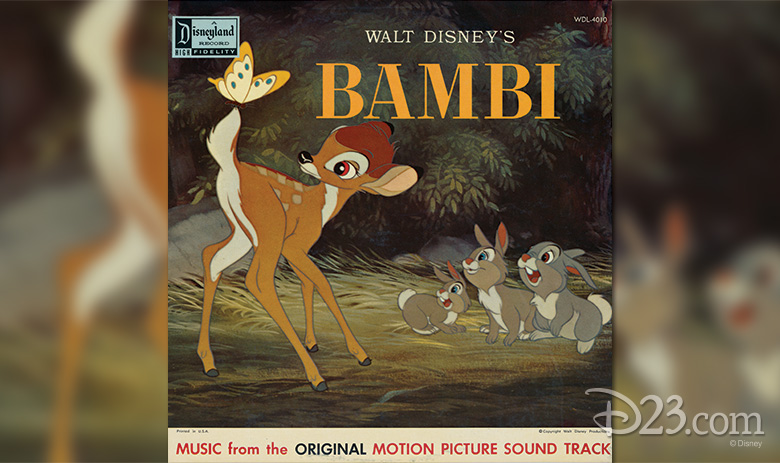

Debney’s childhood memories of Disney aren’t limited to the Studio lot. In the days before home video, employees would sometimes be given permission to bring home 16-mm prints of Disney films to screen for movie nights. Two films made a lasting impression on young John Debney and made him take notice of their music. “One was Bambi,” Debney recounts. “There isn’t a lot of dialogue in that movie. The music has to play a different role—an expanded role. It has to kind of impart upon the audience where you are and what emotion you’re trying to convey.”

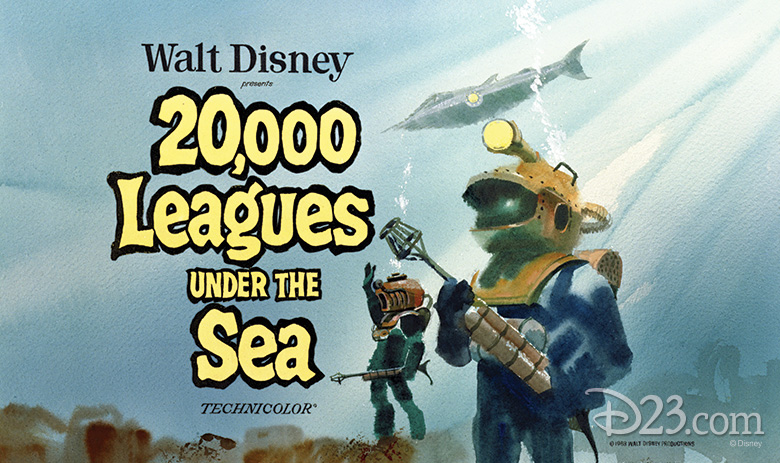

The other film that inspired Debney was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. “I remember the submarine, and how all you saw was kind of the top of it with those lights. I remember hearing the music to that section, in particular, and my pulse would start to race,” he tells D23.

Chapter Two—Taking Up the Baton

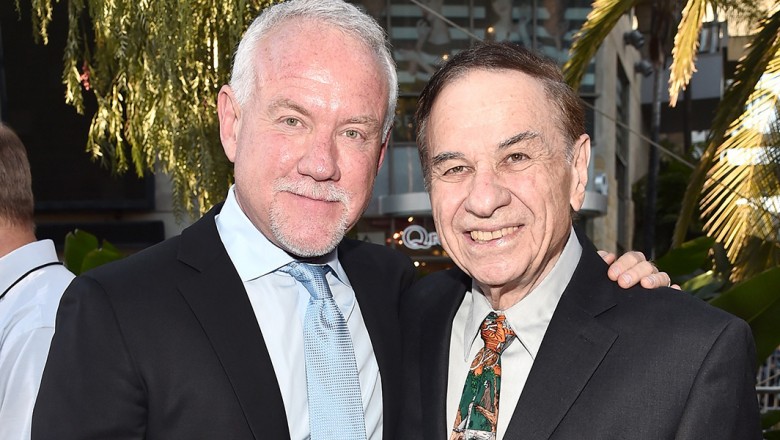

By the time John Debney was about 7 years old he’d developed an affinity for music and had started to play the guitar. Lou Debney turned to a Studio colleague—Disney Legend Richard M. Sherman—and asked if John might be able to meet with him and his brother, fellow Disney Legend Robert B. Sherman. The Sherman brothers happily invited young “Johnny” to spend the day in their office on the Disney lot. “I remember sitting in the corner of their office while they were banging out things on the piano, and just being pretty enthralled by the whole thing,” Debney remembers, his amazement from the experience still palpable. He shares that what audiences saw on screen in Saving Mr. Banks isn’t very far off from the real-life thrill of being in the Sherman brothers’ office: “They’d bang out ideas and he [Richard] and Bob would sometimes have a disagreement, but that was the beauty of the relationship. And they came up with these amazing iconic songs that we all love.”

Debney’s fascination with the combination of music and visual imagery stayed with him, and right out of college he returned to Disney and, naturally, the Studio music department. “I was the kid that made the coffee, and I would take scripts over to people’s houses, and I would do a little copying—a little of everything.” In his first year at the studio, he got to know Disney Legend Buddy Baker—known for scoring Disney films such as Toby Tyler, The Fox and the Hound, and the original three Winnie the Pooh films. “He became a mentor of mine,” Debney says. “He started to give me some assignments and some arrangements and orchestrations to do—just different things for the park mainly, because Epcot was going to be opening.”

It was a time of so much development at Disney that Debney soon became an integral part of the music department. “A lot of it was due to Buddy giving me a chance. I learned so much from him just about discipline and how to write.” Debney also had the opportunity to work with another childhood mentor, Richard Sherman, when he was asked to arrange some of the songs that the Shermans were writing for Epcot. In his time on staff at Disney, Debney would provide music for Disney TV holiday specials, and he was part of the music team when Fantasyland received a new sprinkling of pixie dust in 1983. Even now, Debney can go to Disneyland and ride on the Casey Jr. Circus Train or the Mad Tea Party and hear music he recorded. “It’s kind of a happy surprise when I go down there with my grandson and we ride Splash Mountain and I realize, ‘Oh, I did this,’” he enthuses.

Chapter Three—Writing the Book

The first time that Debney became aware of Disney’s 1967 animated film The Jungle Book was before the movie was released. The Debneys were close to another Disney family—the Reithermans—and John had accompanied his best friend, Bruce Reitherman, and his family on a long vacation. “I vaguely knew at the time that he was doing some voice for some cartoon—I just didn’t know what it was. And I remember that when we got home from our trip, he couldn’t play one day because he had to go back to the Studio to do some pick-up line. And that was The Jungle Book, and he was the voice of Mowgli—and the rest is history,” Debney explains.

At the time Debney learned that Disney was planning a live-action reimagining of The Jungle Book, he was an accomplished film composer with hit films like Hocus Pocus, Liar Liar, and The Passion of the Christ—the 2004 film which earned him an Oscar® nomination. But his connections to the 1967 film and his rich history with Disney convinced Debney that he was the natural choice to score Jon Favreau’s film. Debney and his agent, Richard Kraft, put together a very special scrapbook. “It kind of illustrated my personal history with both The Jungle Book and with Disney as a whole—through my dad, the Sherman brothers, and everything else,” Debney says. That book made its way to Favreau—with whom Debney had previously worked on Elf and Iron Man 2. “It was just one of those things that is so close to my heart that I wanted to at least let everyone know how passionate I was about it,” Debney confesses.

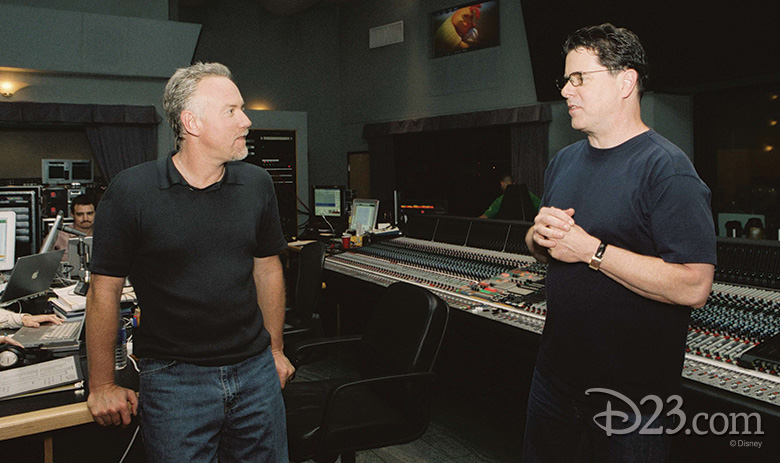

In director Jon Favreau, Debney found a fellow Disney fan—and one well versed in Disney history, as well. For The Jungle Book’s score, Debney says, “Jon wanted a classic, large-scale orchestral score that would be in that ‘Disney-esque’ wheelhouse—because there is a musical style to Disney that we know and love.” Jon also wanted very strong themes, and that was Debney’s first task: composing themes for Mowgli, the elephants, and, of course, Shere Khan. “I always kind of start with the themes,” Debney says about his creative process. “I usually sit at my keyboard and look at the movie a number of times, then start to let ideas flow.” Jon and Debney both wanted to stay true to the story’s cultural background, which created musical “splashes of color,” according to Debney, rich with world music influences along with a large orchestra and a choir. And going back to the beginning, Debney observes that Favreau frequently referenced Bambi while they were scoring the film, and that iconic film was a musical influence for both filmmaker and composer.

Debney spent almost two years bringing music to a brand-new jungle. And during those two years, there were so many moments that took Debney’s breath away, working on a film that he’d felt such passion for. “I’d say the biggest moment for me emotionally, and I think for everybody—all the musicians and the filmmakers—was towards the end. There’s a big piece of music that plays that is sort of a duet between the elephant theme and Mowgli’s theme. It’s a big, glorious, almost three-and-a-half-minute piece of music,” he details. “And gosh, I barely made it through that thing, and I looked back in the booth and I could tell Jon was getting a little misty-eyed. It was just that kind of journey.”

He adds, “By the end of our recording sessions, I think everybody felt this beautiful, almost palpable feeling of what it might have been like to have Walt in the room listening to the birth of a new score for this incredible Disney property.”

And Debney’s close friendship with Richard Sherman also came full circle thanks to The Jungle Book. Sherman contributed new lyrics for “I Wanna Be Like You,” which placed him at Debney’s side for some of the recordings. “He was like my big brother, looking over my shoulder. It was like coming home,” Debney shares. “To look over my shoulder and look through the glass and booth and to see Dick standing there, kind of nodding his head—it was amazing. It was certainly the most wondrous thing I’ve ever done in my career.”

That wonder is still palpable for Debney, even now that the film has been released and is bringing laughter, tears, and thrills to a new generation of fans enthralled by Mowgli’s tale. “Somebody asked me, how long were you on Jungle Book and I said, ‘Well, two years,” Debney tells D23. “Then I kind of caught myself and I said, ‘Well, more like 40 or 50 years, because the journey started with the original Jungle Book and all my connections to that.” “And then fade out, fade in, you know, 40 or so years later, working on the new Jungle Book… It’s been that long of a journey for me personally, and it’s pretty wonderful. I’m very, very grateful and very humbled by it all.”