By Steven Vagnini

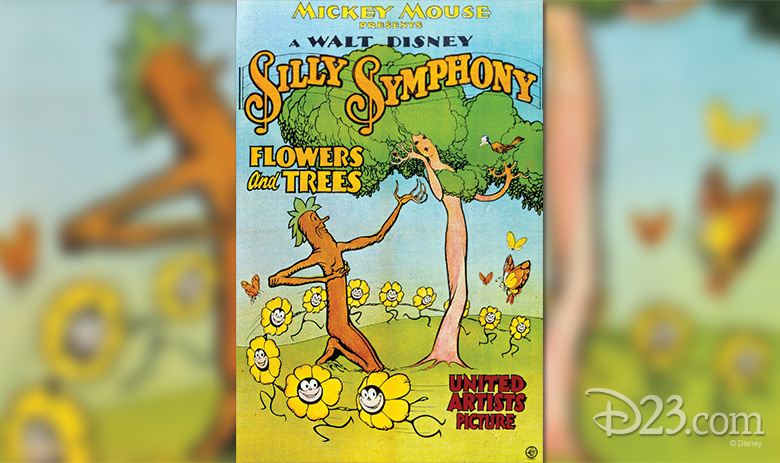

With its breathtaking introduction of color to animated films, Flowers and Trees (1932) brought a sense of renewal to the cartoon industry. Walt Disney’s Studio had done it again, pushing established boundaries in the service of creative storytelling—this time in glorious, new Technicolor. As reflected in this trade ad taken out by distributor United Artists, the short subject was enthusiastically received as a milestone in animation upon release.

Flowers and Trees was the 29th of 75 Silly Symphonies—the animated series that explored music and emotion in vibrant and unexpected ways—and is an outstanding illustration of the proving ground that the series provided. With no central character or theme to limit artists, the Symphonies presented Disney staff members the chance to experiment and open new forays in filmmaking… all in Walt’s enduring quest to elevate the cartoon medium. With trade ad in hand, D23 presents the story behind Flowers and Trees—another memorable milestone From the Office of Walt Disney.

Of Mice and Music

From the very founding of the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio in 1923, Walt Disney sought unique ways to bring his stories to life and distinguish them from other cartoons of the era. “Now they [Max and Dave Fleischer] had the clown out of the inkwell who played with the live people. So I reversed it,” Walt recounted in 1965. “I took the live person and put him into the cartoon field. I said, ‘That’s a new twist.’ And it sold.”

Walt was recounting the Alice Comedies, the groundbreaking Disney series that placed a live actress in a cartoon wonderland. Several years later, the next breakthrough in animation—the incorporation of synchronized sound—helped welcome Mickey Mouse into the hearts of audiences. And while distributors naturally wanted “more mice,” Walt insisted on producing a new cartoon series that, for the first time, relied less on humor and gags and more on mood and music: the Silly Symphonies.

Along the way, Walt took extra effort to infuse new levels of sophistication into his films (oftentimes at the frustration of his brother, Roy.) In 1930, the Studio began using a more delicate positive film stock, despite an added cost of $1,000 per short. And that year, intrigued by the idea of color, he asked Bill Cottrell to experiment by printing a Silly Symphony, Night (1930, pictured above), on blue film stock, attempting to produce a tinting effect to evoke a nighttime setting. Technology always seemed to be one step behind Walt Disney.

An Adventure in Color

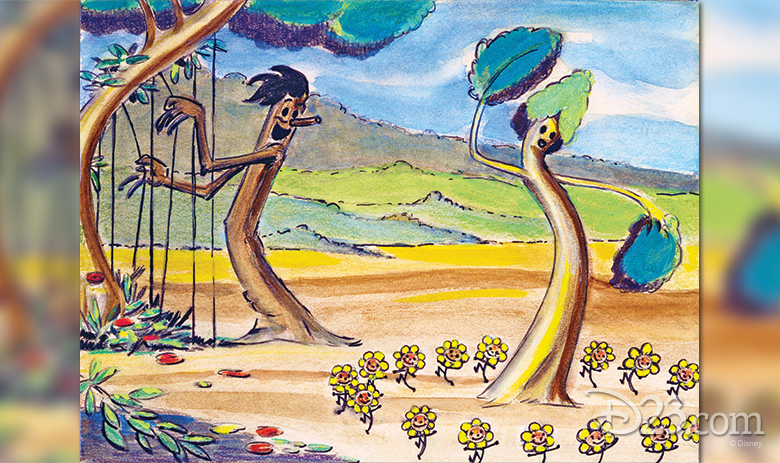

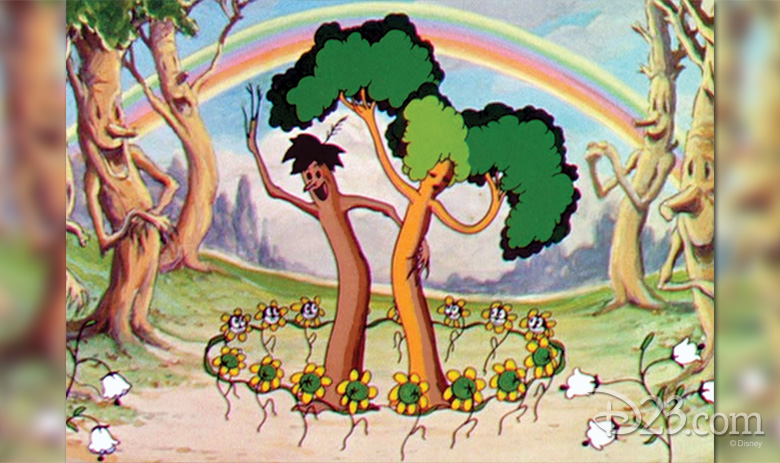

In early 1932, production was underway on a new Silly Symphony cartoon with the working title “Trees and Flowers.” The story would follow a pair of love-struck trees who find their romance threatened by the jealousy of gnarled old stump. After the villain instigates a devastating forest fire, true love wins the day and spring reawakens. With themes by classical composers like Mendelssohn and Beethoven, it would be the first Disney short to feature an all-classical musical score.

In the meantime, Walt discovered a new, three-strip color process that combined negatives of the three primary colors, allowing films to appear in full color for the first time. Recognizing the potential that color could bring to his work, Walt ignored Roy’s early opposition to the “prohibitively expensive” process and signed an agreement with Technicolor, providing the Disney Studio exclusive rights to the process in animated films for two years. He identified his new ode to nature—now titled Flowers and Trees—as the perfect story to introduce the process.

Flowers and Trees was halfway finished when Walt for asked his staff to pause production and convert the film to color. Months of work were added to the project as painters washed the gray shades off of cels and incorporated brilliant new colors. Costs mounted as background artists created all-new environments and technicians made efforts to keep colors from fading under the hot lights of a new camera stand.

Spring Comes to Summertime

The Disney Studio’s bold new risk was ready for release by the summer of 1932. After watching an early screening, Hollywood showman Sid Grauman immediately identified Flowers and Trees as a sensation and booked it at the famous Chinese Theater alongside a major film release, Strange Interlude, in July.

“It received a very wonderful hand at the finish,” Roy remarked to a United Artists executive. Grauman himself heralded Flowers and Trees as a “creation of genius that marks a new milestone in cinematic development.”

The Silly Symphonies Legacy

On November 18, 1932, Walt Disney accepted the first-ever Academy Award® for Cartoon Short Subject. (A Disney cartoon would go on to win the award for that category each subsequent year of the decade.) Flowers and Trees—as well as a special Oscar® for the creation of Mickey Mouse—also marked the first of Walt’s 32 awards from the Academy, a record that remains unmatched in Hollywood.

By this time, the Silly Symphonies had begun to rival the Mickey Mouse series in popularity and would also introduce their own lineup of original, memorable characters, including Donald Duck. But perhaps their greatest legacy is the freedom they afforded artists to explore their trade—from advancing personality animation in Three Little Pigs (1933) to creating a whole new sense of depth and dimension in The Old Mill (1937). Each step of the way, the Disney staff built the confidence and skills needed to break ground on an entirely new motion picture genre: feature animation. “Without the work I did on the Symphonies, I’d never have been prepared even to tackle Snow White,” Walt would later remark.

While the Silly Symphonies serve as bold artistic statements of their era, they continue to be appreciated as pieces of imaginative and enchanting entertainment. “You have to look at them with new eyes… and just look at these things for what they are,” suggested composer Richard Sherman during an interview for the Walt Disney Treasures series. “And they’re very thrilling. You step into another world. A sweet world, an innocent world. And a very lovely, laid-back world. The kind of world I sort of miss.”

When D23 Gold Members open their 2016 D23 Member Gift, “From the Office of Walt Disney,” they’ll discover a recreated Silly Symphonies trade ad, heralding the arrival of color to animated films and noting the success of the animated cartoon series.

This advertisement is one of 23 reproduced treasures from the Walt Disney Archives, celebrating major milestones in the life and career of Walter Elias Disney. To learn more about this first-of-its-kind collection, visit D23.com/OfficeofWaltDisney.