Five years ago, D23: The Official Disney Fan Club set out to add more ways for Disney fans to experience the magic. And it’s been a blast bringing people of like minds together in the parks, at the Walt Disney Studios, and many other places across the country. We could have never imagined how just how many once-in-a-lifetime experiences we would share together.

We asked our staff to share their ultimate Disney fan moments over the past five years and here’s what they said. Sorry for the quality of some of the photos. Many of these photos are from our personal cameras and mobile devices!

“When I started my job with Disney I never thought I’d be a part of something like D23. After 21 issues of Disney twenty-three magazine (working on 22 and 23 now!), I think my favorite was probably Winter 2011, when the Muppets made their return to the big screen and graced our cover. I am a huge fan of Kermit and the gang, and as I was designing the cover for that issue, I got the crazy idea of making our entire cover, and each Muppet, felt. It turned out to not be entirely feasible for various reasons, but we were able to make the entire back cover and our masthead fuzzy and Kermit green. The entire printer that produces twenty-three was covered in fuzz! That issue still sits on my coffee table… one of probably 20 Kermit’s found in my office.”

—Jared Cohen-Richards, Art Director, Disney twenty-three

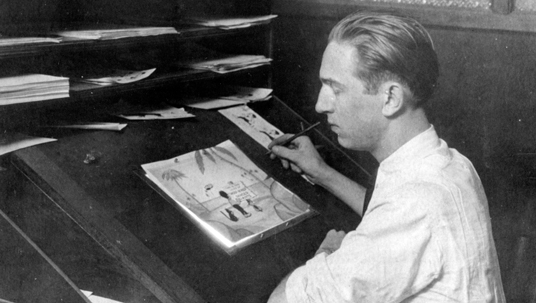

“One of the things I love doing at D23 is taking our members on our tours of the Walt Disney Studio Lot and Archives. Being a huge Disney fan myself, sharing the heritage of Disney with people who embody that same enthusiasm is incredible. We’re always looking at ways to make the tours even better, whether that be through personal anecdotes or new, fun facts we learn. I was treated to both several years ago. We had just had a member event on the lot, and several of us were walking Disney Legend Richard M. Sherman and his wife, Elizabeth, back to their car from the Studio Theatre. On the way, we passed the Shorts Building—actually two buildings that were moved over from the when the Studio was located on Hyperion Avenue in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles and then connected. As we passed, Richard turned to me, pointing up to a corner window and said, “That’s where my brother and I had our office. Walt would come there and give us notes.” Now it’s one thing to learn a fact about something by reading it in a book, but to have Richard himself point up to that window and tell me that little tale was an entirely different thing. It completely enriched my love for the legacy of our company, and it gave me a terrific story to share with D23 Members whenever I give a tour.”

—Jeffrey Epstein, Marketing and Publicity, D23

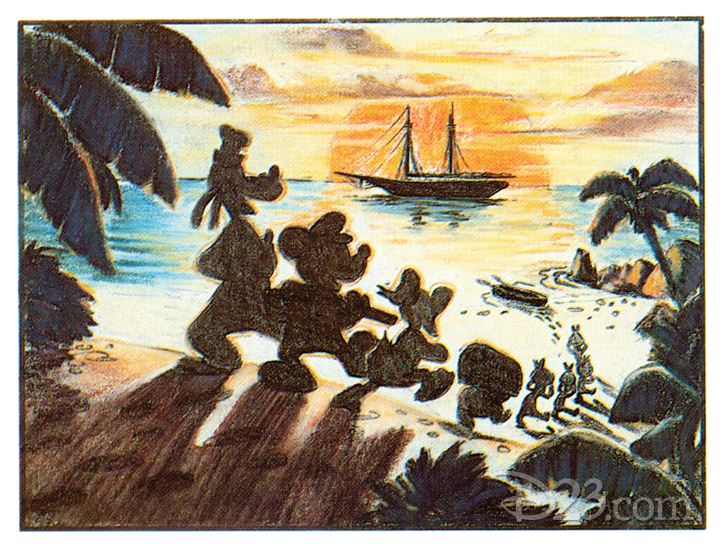

“On March 14, 2012, 100 eager D23 fans boarded a chartered bus in Kansas City, Missouri to travel back in time to a place that Walt Disney would always call his home.” D23’s Journey to Marceline celebrated the memories of Walt’s hometown with a one-of-kind tour experience that included a visit to the Walt Disney Hometown Museum, a screening at the Uptown Theatre, and a sunset reception at the Disney farm. The mayor came out to officially proclaim March 14th as D23 day in city of Marceline. This special event brought to life Marceline’s rich Disney heritage and left guests, including myself, with one unforgettable day that we’ll always cherish. ”

—Michael Buckhoff, Archivist, Walt Disney Archives

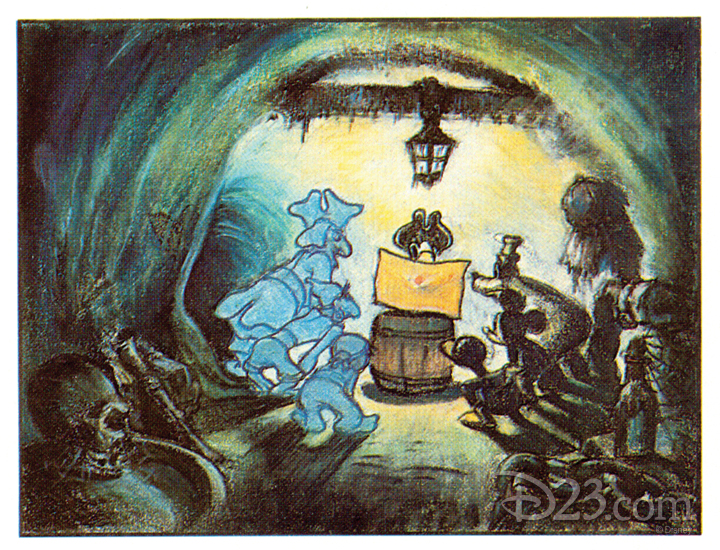

“Many D23 Members have told me that they have ‘Disney bucket lists,’ or a list of fantasy experiences they’d love to have with Disney. Ever since I was a little girl, mine has been to take a peek behind the scenes of Fantasmic! At Disneyland Park. There’s something about the storytelling and magic of the show that absolutely never gets old, and I’m quick to tell people that it’s my favorite ‘Disney thing’ of all. So when I got the opportunity to escort the old Maleficent dragon prop from the show from to its new home at Treasures of the Walt Disney Archives at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, it was a dream come true. That’s what I love most about D23, the incredible opportunity we have to bring fans up close and personal with whatever it is they love most about Disney. It’s been such a privilege to help our members check items off their Disney bucket lists, and in the process I’ve gotten to check some items off mine too!”

—Kelly Griffiths, Marketing, D23

“Visiting Marceline Missouri was an amazing experience! I was born and raised in Los Angeles so I was immediately caught up in the small town charm of Marceline, and a bit jealous of how close people there are. Add to that the fact that the town has this wonderful Walt Disney history (that they are extremely proud of) and it just all made for a great visit! This photo is some of our team that went out for the event and young ‘Walt’ and his sister ‘Ruth.’ They were great kids and in addition to their starring roles, they also acted as our tour hosts. Loved this place and hope to go back someday!”

—Toni Wehn, Special Events, D23

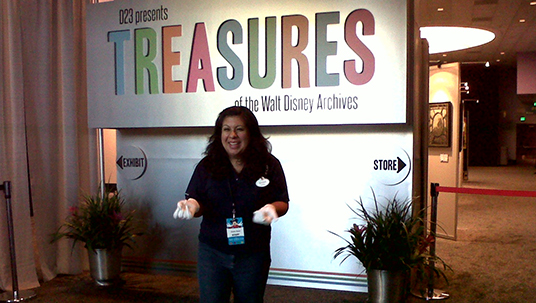

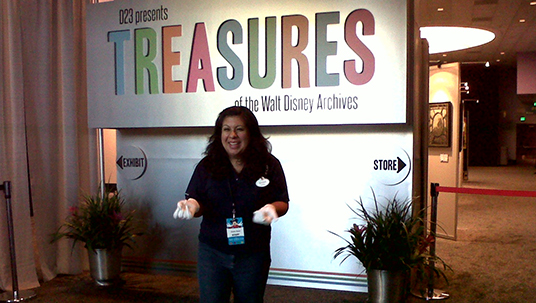

“Here is a pic of me out front of the entrance to the exhibit from D23 Expo 2011. It was my first time assisting our team with setting up an actual exhibit other than my usual ordering of supplies so it was a really big honor for me to experience it all.”

—Alesha Reyes, Administration, Walt Disney Archives

“Over the 4 years that I’ve been with D23, I have been given the opportunity to have so many fantastic adventures, doing things I never thought, as a Disney fan, Id get to do. From hearing Julie Andrews speak words that I wrote, to traveling to New York City with Billy Stanek while we did a whirlwind tour of Good Morning America, Newsies, and The Lion King, it has truly been a dream come true. But for this fanboy, my best memory of my time with D23 has to be the evening we shot the Avengers episode of Armchair Archivist. In the weeks leading up to the shoot, we were told that Marvel Studios President Kevin Feige would have only a few minutes to talk to us in between giving presentations at USC’s school of cinematic arts. So we were prepared… questions prepped, shots planned, we were ready to go. When Kevin arrived, we instantly struck up a conversation and before we knew it, we had spent 15 minutes just chatting about movies and Disney (Kevin is a Charter member of D23!), fearing we were going to run out of time to shoot the episode, we rolled camera, and what you see in the final episode is literally just two movie fans talking and looking at props. He was so gracious with his time, even coming up with an idea for a Marvel-esque post credits scene for the episode. It was truly once and a lifetime and after 16 years in the business, its a shoot that I hold at the top of my list. It wasn’t until after, that I realized, the experience I had with Kevin, is exactly what D23 is all about, bringing the fans closer to the movies, music and the wonderful world of Disney than ever before. And in that moment, I was the biggest fan of them all.”

—Josh Turchetta, Host, Armchair Archivist

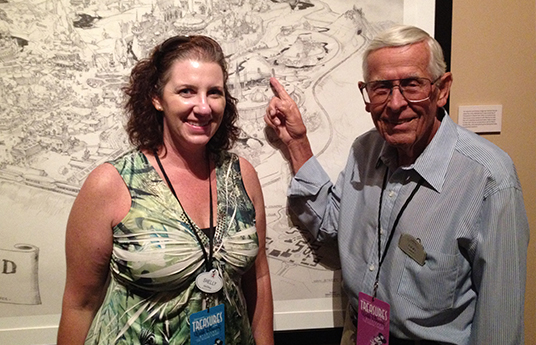

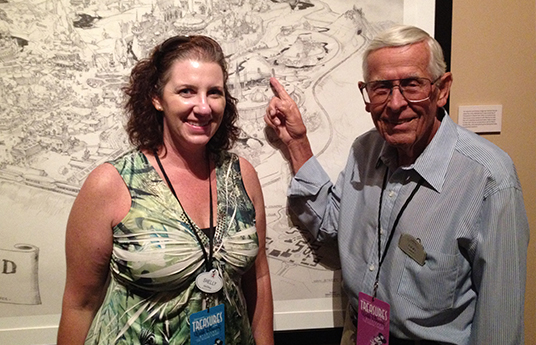

“When I see Bob Gurr, I like to remind him that before I worked in the Walt Disney Archives, I used to drive the Mark V Monorail trains at Disneyland. He likes to reply, ‘But I drove the FIRST one!’ In this photo, we are inside our Treasures of the Walt Disney Archives exhibit at the Reagan Library on opening day July, 2012, and he’s pointing out the concept for The Disneyland-Alweg Monorail System in Tomorrowland on the map. I think my experience as a 20-year cast member has now come full-circle! Thanks D23 for the fun memories I will never forget!”

—Shelly Graham, Walt Disney Archives

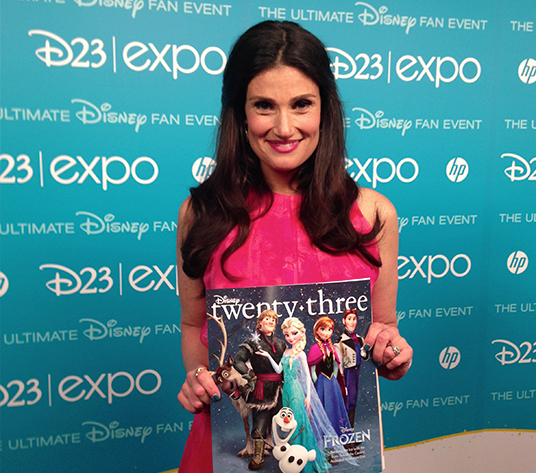

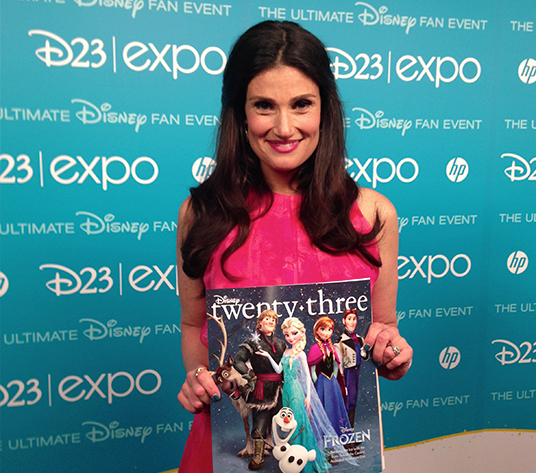

“As part of the D23 social media team, I really loved being a part of the D23 community and interacting with many of you behind the scenes. Although I had fun all year long, the D23 Expos were always a special time since we got to share some really awesome and exclusive content—I’m pretty sure most jobs don’t require hanging backstage with celebrities like Robert Downey, Jr. Jason Segel, Anika Noni Rose, and countless others! My favorite moment this past D23 Expo was meeting Idina Menzel and taking this picture for the D23 social media accounts—I had always been a huge fan of her so meeting her and seeing her perform was an unforgettable experience. Thank you for the memories, D23!”

—Patricia Sheppard, Manager, D23.com and Social Media

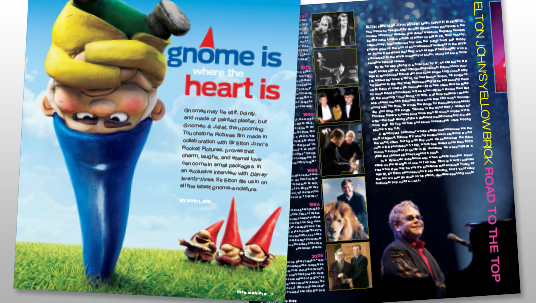

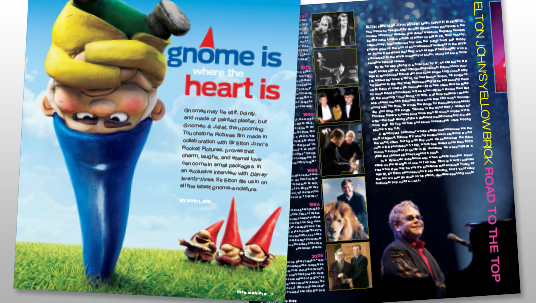

“It’s not every day you get a phone call from Sir Elton John, but I was fortunate enough to enjoy that once-in-a-lifetime moment in 2011 when I was writing the story “Gnome is Where The Heart Is” for the spring 2011 issue of Disney twenty-three. I’m dating myself, but Elton John was the first concert I ever saw, in 1974—an event that left an indelible impression on me—so when I picked up the phone for our interview and heard, ‘Hello Max, this is Elton,’ I was pretty much floored. And wondering how it could be possible that I had made the journey from Detroit and the upper deck at Olympia Stadium to Los Angeles and this unforgettable moment talking to Sir Elton.”

—Max Lark, Editor in Chief, Disney twenty-three

“Take the thrilling feelings you get on the last day of school, at a wedding, and, well, on a trip to Walt Disney World Resort, blend them together, and that’s how many of us felt on May 14 and 15, 2011, as we gathered to celebrate 40 years of Vacation Kingdom memories at Destination D: Walt Disney World 40th. During this weekend event, Disney Legends, Imagineers, entertainers, Cast Members and, most importantly, 1,200 D23 members and their Guests commemorated the fascinating development and evolution of the Florida Project with rare, behind-the-scenes glimpses. Although most of my work was done behind the curtain, helping produce and operate the show, my heart was among D23 members (and my family!) in the audience. Who can forget the musical finale uniting Richard Sherman, Dreamfinder and Figment, the Main Street Philharmonic, the Kids of the Kingdom, the Encore! Cast choir and band, and other celebrated performers from Walt Disney World past and present? What a weekend!”

—Steven Vagnini, Archivist, Walt Disney Archives

“My favorite D23 moment was at D23 Expo 2011. There was so much to help with behind-the-scenes to make the expo a great event that I didn’t really expect to see any of the great panels or performances scheduled for the weekend. I ended up being in the right place at the right time though, and was pulled up on stage to help present a painting to Dick Van Dyke. Later, I had the privilege of getting to talk with him a bit more after his performance. I grew up watching his movies and TV show, so it was very surreal (and awesome!) to meet him in person.”

—Francesca Cramer, Administration, D23

“A little bit of rain wasn’t going to dampen my mood in January 2012. I was on my way to interview to Dick Van Dyke—a renowned actor and Disney Legend that I’ve admired since I was a child. Who wouldn’t be excited? I stepped inside a voice-recording studio for the very first time—which was super cool in and of itself!—and immediately heard a very familiar voice singing a song. I quickly made my way over to the control room of the studio, and there he was—Bert himself, Dick Van Dyke! I was able to watch him voice a brand-new character for Disney Junior, and after he was finished, I met him inside the sound booth for an interview. It was one of those pinch-me moments that I’ll never forget, and one of the things that I love about my job at Disney.”

—Cynthia Momdjian, Writer, D23.com and Social Media

“Last April D23 sat down with Marty Sklar for an interview about his book Dream It! Do It!: My Half-Century Creating Disney’s Magic Kingdoms. I was privileged to be a part of the crew that was invited to his house to capture footage for D23.com, which I know many of you have seen. I normally don’t get the chance to go out on video shoots, so when I was asked to go I got really excited. Meeting Marty for the first time and hearing him speak about his storied career that April morning definitely makes it at the top of my list for favorite D23 moment.”

—Cris Bernabe-Sanchez, Graphic Designer, D23

“Books. Carpet. Decorations. Furniture. These everyday things populate our daily lives to some degree, be it at work, at home, at play, or on the go. However, it’s not everyday that one has the chance to showcase and reassemble a collection of these effects from the Burbank studio office of Walt Disney. During the Walt Disney Archives’ preparation for D23 Presents: Treasures of the Walt Disney Archives at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum, the Archives staff spent many hours resetting nearly every piece of ephemera from Walt’s Formal Office in a recreated exhibit space at the museum. This process was exceptionally rewarding, and helped the entire staff experience a further and deepened sense of respect for Walt, the man. However, for me, the most rewarding part of the entire (and lengthy) installation process was seeing our guests’ reactions when the exhibit doors opened for the gala grand opening, allowing all to experience our recreation of Walt’s Formal Office in its finished state. That one moment, watching as a mixture of delight and reverence swept across the excited audience filled with D23 Members and special guests, is something I’ll never forget.”

—Kevin Martin Kern, Collection Specialist, Walt Disney Archives

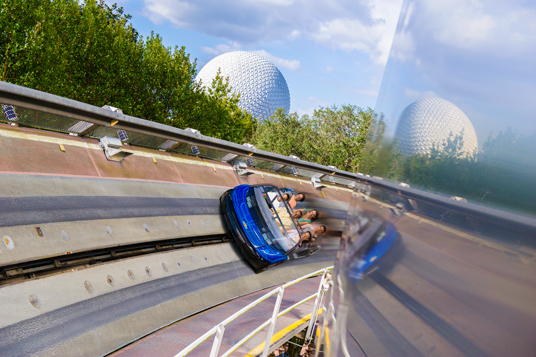

“It doesn’t get any better than spending a morning with Marty Sklar. And if you were with us at D23’s Destination D Walt Disney World 40th Anniversary event then you know exactly what I am talking about. Marty was there for two days of panels and presentations about the resort’s history. This Disney Legend worked side by side Walt Disney throughout his career, and was tasked with making Walt’s final dream—E.P.C.O.T.—a reality, which I should also admit is my favorite Disney park. While most of my time is spent behind a computer or iPhone bringing Disney fans the latest news and stories from the archives, I often get to step out of the office and experience Disney and hear from its creators firsthand, along with you. Thanks for letting me be a part of your Disney fan club.”

—Billy Stanek, Editor, D23.com and Social Media