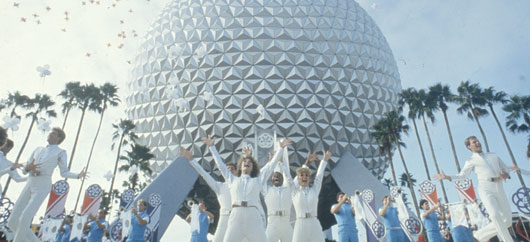

A decade on, there’s still debate about when exactly the 21st century began. For Disney fans, that pivotal moment didn’t come at the stroke of midnight in 2000, or even a year later. At the heart of Walt Disney World, under the warmth of an autumn Florida sun and amid spectacular pageantry and color, the dawn of the new millennium arrived nearly 20 years earlier than it did for the rest of the world—on October 1, 1982, when EPCOT Center made its long-awaited debut.

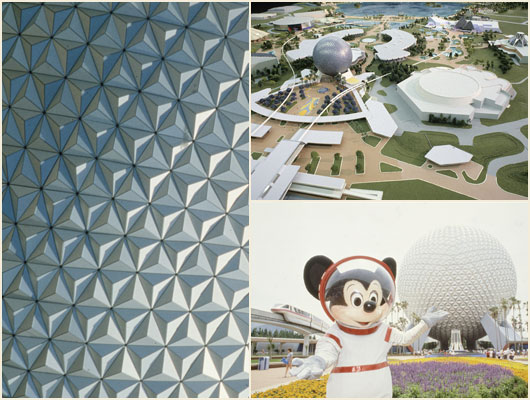

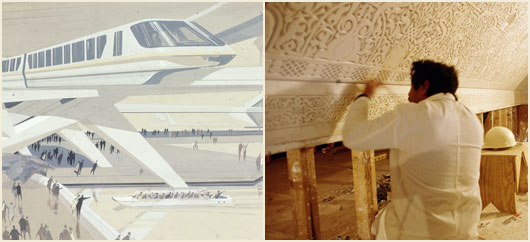

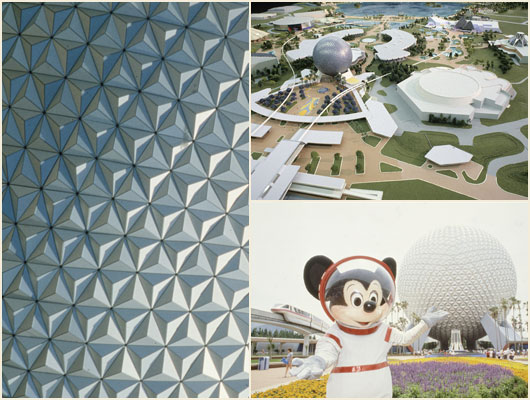

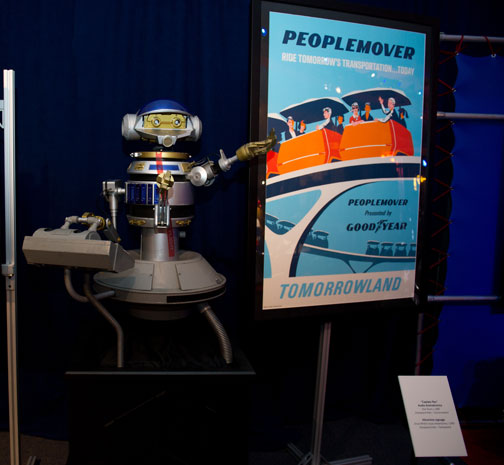

On display were fiber-optic systems, video-conferencing kiosks, computer-generated animation, an army of Audio-Animatronics® figures, and the world’s first (and, to this day, only) self-supporting geodesic sphere, a gleaming silver 18-story-high wonder. And that’s just what the public saw.

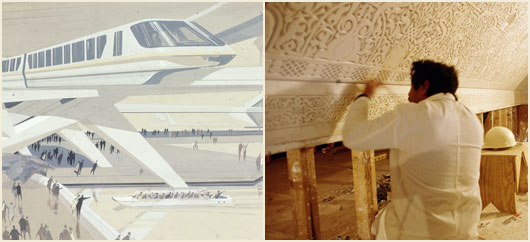

Behind the scenes, an elaborate and massive infrastructure moved everything from guests to digital data, from water to trash, in an intricate and choreographed system that combined technological innovation with Disney’s unique brand of showmanship.

“Walt was always trying to go beyond what he did before”

If EPCOT Center seemed, at the time, the pinnacle of Disney know-how, that’s because it was—the culmination of nearly two decades of thinking, dreaming, researching, and designing that began with Walt Disney himself and reached fever pitch while his Company worked with other major American companies to build exciting pavilions for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. For Pepsi-Cola’s pavilion at the World’s Fair, Disney produced it’s a small world. Ford’s Magic Skyway was designed by WED Enterprises (later renamed Walt Disney Imagineering), and General Electric teamed up with Disney for Carousel of Progress. For the state of Illinois, WED created Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.

Walt was intimately involved in planning those attractions for the World’s Fair, explains Disney Legend Marty Sklar, retired Imagineering vice-chairman and principal creative executive (and Walt’s ghostwriter). “Walt would go around to the laboratories of major companies, and anytime Walt would go there, they would trot out the newest things they were working on. Walt loved seeing these concepts, and he loved the technology.

“There were three reasons Walt got involved with the World’s Fair,” Marty says. “One, he wanted to bring those attractions to Disneyland. Two, he wanted to prove a Disneyland could work on the East Coast. And three: EPCOT.”

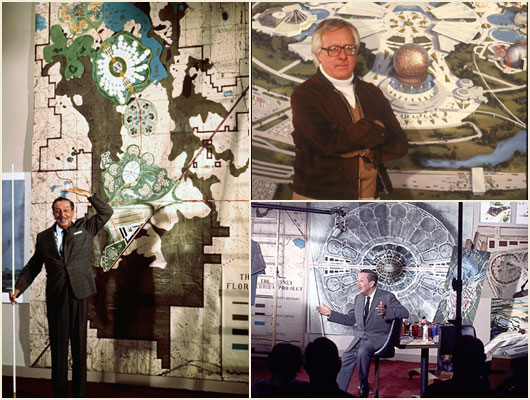

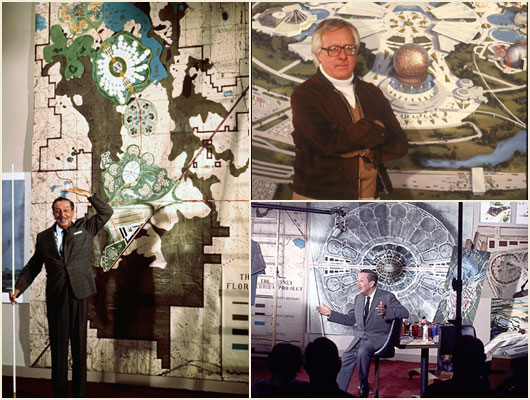

“EPCOT” rapidly became one of Walt’s favorite words—and the most prominent project for his company. It was an acronym he and the Imagineers coined from the phrase “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow” as they worked on their city of the future. Walt was eager to show it to the public, but when he took part in a November 15, 1965 press conference to announce Walt Disney World, Epcot wasn’t mentioned—though it was very much on his mind. (Editor’s note: In 1994, the name “EPCOT Center” was shortened to Epcot, which is how we’ll refer to it here.)

Back in California, plans were further along than many people, including those who worked for Walt, realized. A private conference room Walt had set up was off-limits to all but a few, and it held amazing plans. An East Coast theme park was just the beginning.

In the spring of 1966, Walt met with Marty. “He said, ‘Let me tell you what I’m thinking,'” Marty remembers. “And then he just started talking. And talking. And talking. He kept coming back to one phrase: ‘To meet the needs of people.’ That’s what Walt wanted to do. There were things in our society that frustrated him. Traffic. Education. Even collecting trash.”

“The entire underpinning [of Walt Disney World] was based on Epcot“

As Walt talked, Marty took notes, and the full scope of Walt’s ambition fell into focus. In four decades, he had moved from black-and-white silent cartoons to color feature-length animated films, then to live-action movies and theme parks. Now he was talking about building a city. It made sense, given Walt’s history, Marty says. It combined everything he had done so far—turning fantasy into reality, blending education and entertainment, creating real worlds from imaginary ones.

“Walt was always trying to go beyond what he did before,”Marty says. “Walt made it very clear that he was not interested in what we did yesterday. He wanted to know what we could do today and tomorrow.”

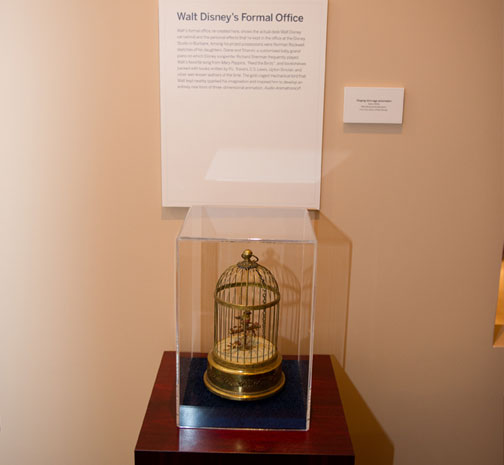

During the planning and construction of Disneyland, Walt had been introduced to the basic concepts of urban design and slowly became a self-taught expert in the field. Such seemingly dry concepts as city planning and urban decay fired his imagination. When Disney’s Chief Archivist Dave Smith catalogued Walt’s office in 1970, one of the books on a shelf behind Walt’s desk was architect Victor Gruen’s The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure.

“Walt was serious about that city,” Marty explains. “And he had a lot of work being done at the time” to explore its viability. Walt asked for Marty’s help to coalesce his thoughts so he could produce a film to explain the project, and, over the next several months, Marty wrote a script for a 24-minute film that detailed the “Florida Project.” In the film, an ebullient Walt explains the concept of Epcot—a full-scale city of the future where people would live, work, and play in comfort. An international shopping district would re-create scenes from around the world, and American industry would have a showcase for the latest technologies.

Walt shot the short film in October 1966. Eight weeks later, he was gone.

The brief-but-potent film, however, lived on. It was shown a handful of times in early 1967 to key constituencies: the Florida Legislature, invited guests (for a packed presentation in a Winter Park theater), and once on statewide television. The film proved vital in convincing both the Legislature and voters that Disney’s Florida Project should be approved, which it was. From the moment the project was given the go-ahead, Marty says, the Company’s resources were dedicated to getting Walt Disney World up and running and to regaining confidence in the absence of its founder and leader.

In October 1971, the first phase of Disney’s Florida Project—Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom—opened on time and on budget. And though it might have seemed on the surface that the Epcot idea had been abandoned, nothing was further from the truth, according to Marty. “So many of the things that Walt wanted to do, we did. We were already running a city.”

Indeed, the Reedy Creek Improvement District, a governmental body overseeing the development of the more than 40 square miles of land that make up Walt Disney World, was created during Walt’s final months with the intent of bringing Epcot to life. Its building codes and planning guidelines were initially crafted with an eye toward Walt’s plans for Epcot. “The entire underpinning [of Walt Disney World] was based on Epcot,” Marty reflects.

Without Walt, though, constructing an actual city seemed virtually impossible. “It was such a big idea,” Marty says, “not just beyond anything Disney had done, but beyond anything anyone had done.” And yet, the concepts behind Epcot were enormously compelling, in part because they represented everything that Walt had focused on in his final months.

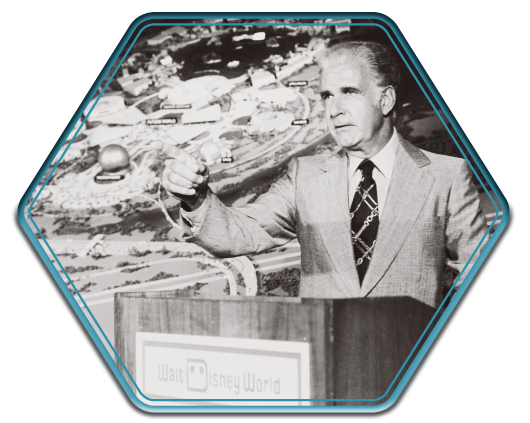

By 1974, it was clear that Walt Disney World was an unqualified success. That May, Marty’s phone rang. It was Disney’s then-president, E. Cardon “Card” Walker. Marty recalls the brief conversation vividly: “He said, ‘What are we going to do about Epcot?'”

It became one of the most vexing, fascinating, and creatively overwhelming questions that has ever faced the Imagineers.

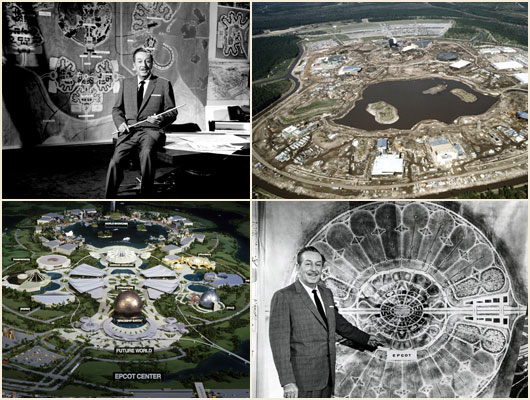

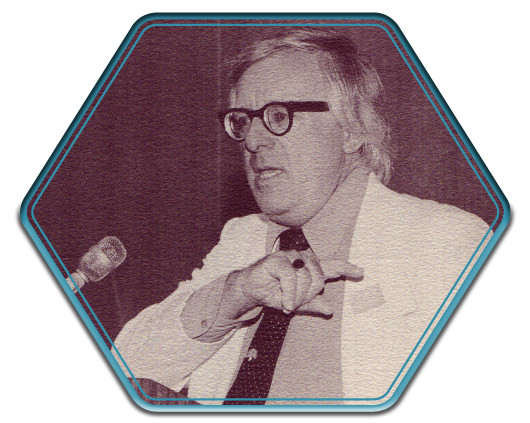

Marty tasked Imagineer Peggie Fariss with convening an unprecedented series of conferences to explore some of the most important topics of the day—among them, energy (this was shortly after the 1973 oil crisis), food production, communications, oceanography, transportation, and global affairs. Held in Florida beginning in 1975, they became known as the Epcot Forums, and one of the first people Peggie asked to participate was renowned science-fiction author Ray Bradbury. He remembers the Epcot Forums well—especially the humility with which participants approached them.

“We [as a society] didn’t know who we were,” Ray tells Disney twenty-three. “I told them that they should present the history of mankind to people. We needed to rediscover where we came from, and where we would like to be going, so I kept talking about this again and again.”

Other Epcot Forum participants included Melville Bell Grosvenor, former head of National Geographic; oceanographer Robert Ballard; researchers from the University of Arizona; and chief scientists from General Motors.

“What we found was quite interesting,” Marty says. “Almost everybody we met with said, in one way or another, that people didn’t really trust industry, they didn’t trust government—but they did trust Mickey Mouse.” The idea of blending Disney storytelling techniques with academic and scientific research was roundly endorsed.

Walt had envisioned a city where research-and-development techniques could be presented, but the problem was that nothing of the sort had ever been tried. On the other hand, the Magic Kingdom proved that a Florida theme park could work. And the 1964 World’s Fair still loomed large, as did previous Fairs, which had been used to showcase American ingenuity and global cultures.

“I had always dreamt of building a World’s Fair,” Ray says. “When I was 12 years old, I went to the [1933] World’s Fair in Chicago and fell in love with the future. If they could do that to me when I was only 12, it could happen to many other people. I went crazy; I went mad. I exploded with emotion! That fair caused me to go home and prepare myself for the future, to write about it, to change the future. Epcot could help other people do the same thing, to prepare them to explode with love and emotion, to encourage them to change the future.”

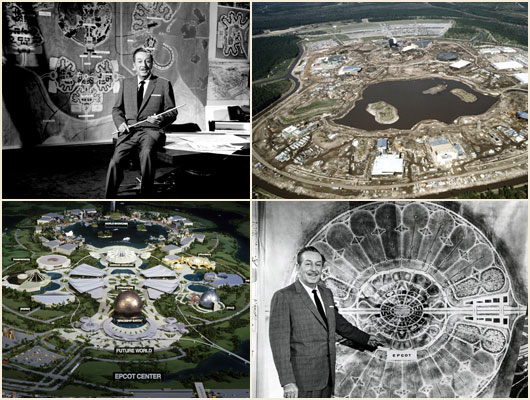

Epcot’s basic structure began as two distinct themed areas in different locations at Walt Disney World—both more serious and far-reaching in ambition, and more straightforward and simple (though futuristic) in design, than a typical theme park. And both areas drew inspiration from the World’s Fair concept that Ray and others had championed.

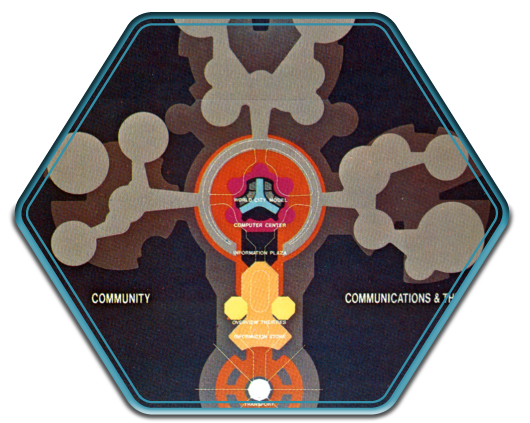

The first themed area was dubbed the Walt Disney World Showcase, and would explore the countries, people, and cultures of the world. Plans initially called for it to be built just south of where the Transportation and Ticket Center is today. The other was named the EPCOT Future World Theme Center, and was conceived as a vision of the future as seen through the eyes of American corporations. That collaboration with leaders of U.S. industry was always crucial to the Epcot concept, both as city and theme park. “Walt said there was no way any one company could do this,” Marty remembers. “It was all about ideas, about things that were happening in the world, and about Disney’s ability to communicate those ideas, to tell those stories.”

The Future World Theme Center, whose name was frequently shortened to “the EPCOT Center,” was proposed for the middle of the property. Walt had always touted the “blessing of size” as a key attribute of the Florida project. “We felt there was room for these two parks,” Marty says. “But as we tried to sell the idea [to corporate sponsors], we weren’t getting very far. One day, we had a big meeting with [top Disney executives] Card Walker and Donn Tatum. John Hench and I looked at the two models, and we just put them together.” The two legendary Imagineers had made a seemingly simple change, but it worked.

With the basic design concept for Epcot settled, Ray Bradbury found himself spearheading the development of one of the signature attractions, a concept called Spaceship Earth, which built upon his passion for telling the story of human beings. It would be the centerpiece of Future World. For Ray, its importance could not be overstated.

“They put me in charge of writing the original script for Spaceship Earth, to tell that wonderful science-fiction story inside it,” Ray says, his voice bursting with pride nearly three decades later. “And when you come out, you go into the future. You’ve been in a spaceship, a time machine, you’ve left the Earth, you’ve gone to the moon, and if that isn’t a great start, I can’t think of one!”

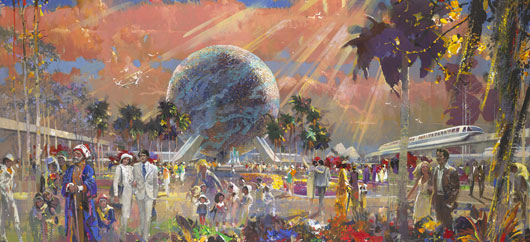

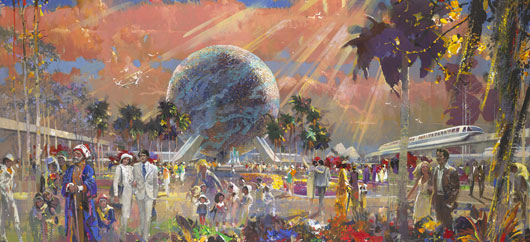

Some of the most storied names in Imagineering history—including John Hench, Dorothea Redmond, Tim Delaney, Harper Goff, and Herb Ryman—conceived remarkable images of what Epcot could be. These kinetic, evocative paintings and drawings helped cement the notion that Walt Disney World could convey more than fantasy, that a vacation could encompass exploration, discovery, and learning.

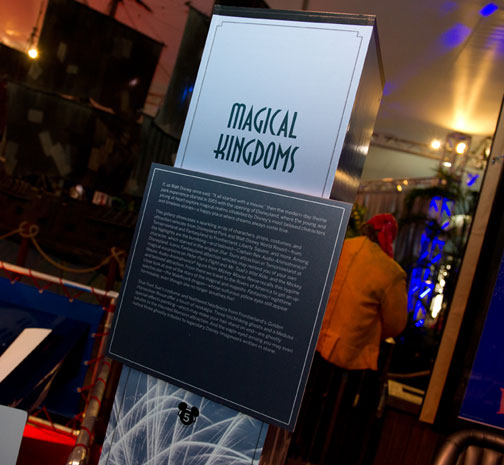

What had been two disparate concepts began feeling more and more like a uniform whole as Epcot took on the hourglass shape so familiar to today’s visitors. Future World anchored the north side, with World Showcase laid out around a large lake on the south. Conceptually, they’re radically different, but together, they contain an important underlying thread: the notion of progress, of working together to achieve a better tomorrow. One part of Epcot shows us what is possible, the other shows us who will make it happen: We will. By understanding and celebrating our differences, we can create a better future.

“The whole of Epcot teaches us how miraculous we are,” Ray says. “We are very special people. We are part of something that began millions of years ago. So, all the time, on every side, Epcot points to you and says, ‘You are individual. You are creative. I hand you the future; step into it. Believe and go forth.'”

By its placement just inside the main entrance, Spaceship Earth would serve as a beacon to guests, its location encouraging them to begin their visit with a ride through human history, communication, and innovation. From there, they would be ready to more fully appreciate the opportunities, challenges, and subjects being presented to them.

Inside Future World, Spaceship Earth would only be occasionally visible, with the huge hub of CommuniCore (now Innoventions) often obscuring its view. But from World Showcase, the geodesic sphere would almost constantly loom on the horizon, a subtle reminder that our cultural connections drive the progress of our never-ending trip aboard Spaceship Earth.

Likewise, Epcot itself was designed to be situated at the geographical heart of Walt Disney World—since it was the center of so many of the ideas contained in Walt’s final visions. By 1976, the concept of Epcot began to make perfect sense as a theme park. But it still had to be built. Not even the initial phase of Walt Disney World was as large. Indeed, Epcot was, for many years, the largest single-site construction project ever undertaken, requiring more than three years of around-the-clock labor. And it presented its share of logistical challenges.

“When we started on Spaceship Earth,” Marty explains, “they wanted to put it on the ground and do three-fourths of a sphere. A group of Imagineers went to John Hench (who had conceived of making Epcot’s visual icon a full geodesic sphere) and said, ‘We can’t do this.'” John came up with the solution: Create two hemispheres and hang the bottom from the top.

Inside The Land pavilion, the single largest attraction in Epcot’s Future World, there was a smaller problem that was no less pressing. Working in conjunction with the University of Arizona, Imagineers had designed a massive greenhouse to showcase new concepts in agriculture. But plants need to be pollinated, and pollination usually requires bees… and bees don’t typically mix well with large numbers of people. To this day, plants inside The Land are pollinated by hand, an exacting process.

Then there was the seemingly simple issue of where to place World Showcase pavilions. For a while, the United States was front and center, the transition point from Future World to World Showcase, much as the “host” pavilion had always been at a World’s Fair. But World’s Fairs are temporary. This was forever. Should America really be entitled to position itself more prominently than other countries?

Ultimately, the United States was placed at the far end of World Showcase. Guests wanting to see its presentation would have to pass by and discover other countries and cultures. Mexico and Canada, America’s neighbors to the south and north, became the entry points for guests arriving from Future World.

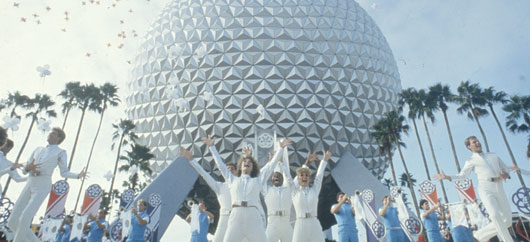

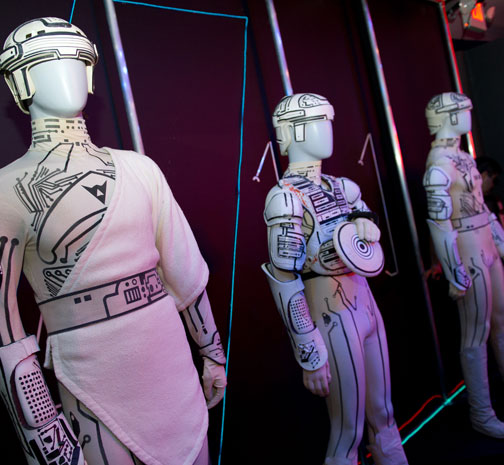

As Epcot progressed, a thousand challenges and problems needed to be addressed, each as unique as the project itself. As the kaleidoscopic, tumultuous decade of the 1980s began, construction continued on this Walt Disney dream. Advertising and public relations programs were developed to herald “The Dawn of a New Disney Era” and, perhaps most impressively, the promise that “The 21st Century Begins on October 1, 1982.”

the kind of hope and optimism that Walt himself felt so deeply”

When that day finally arrived, it felt to Ray as momentous as the actual turn of the century did years later. Perhaps more so. Doves flew past Spaceship Earth. Performers clad in futuristic white jumpsuits sang, danced, and imparted a sense of jubilation and optimism. “Through the crowd came John Hench,” Ray recollects, “and when he held me and hugged me, I thought, Oh, my god. This is the greatest thing! It is the greatest moment in my life, in my world, to be part of the birth of Epcot.”

Like the world around it, Epcot evolved in the decades that followed. Technologies that had seemed impossibly far off became familiar. Attractions were updated to reflect new developments and were sometimes changed entirely—the old giving way to the new just as Walt had promised from the start. But at its heart, the spirit that infused Epcot throughout its development, its construction, its opening, and its infancy never wavered. Epcot may seem different today, Ray says, and that’s precisely the point: “We can keep growing with it. We can change parts of it. We can even rebuild parts of it. But it will continue to influence us.”

“Epcot,” Marty concludes, “is about trying to communicate hope and optimism to people…the kind of hope and optimism that Walt himself felt so deeply.”

By D23’s John Singh with special thanks to Steven Vagnini for his research and contributions.

What’s your favorite Disney park attraction?

What’s your favorite Disney park attraction?

Unlike the Partners statue at Disneyland park, which sits on a pedestal, the Storytellers statue will be at eye level, reminding cast members and guests alike of the humble beginnings of Walt’s history-making story.

Unlike the Partners statue at Disneyland park, which sits on a pedestal, the Storytellers statue will be at eye level, reminding cast members and guests alike of the humble beginnings of Walt’s history-making story.