By Jim Fanning

A timeless trek through a lyrical forest, Bambi (1942) is Walt Disney’s masterfully crafted animated tale of a young fawn and his family and friends as he discovers the glories—and the hard truths—of life in the wilderness. Delicately rendered but with compelling scenes of great power and dramatic action, Bambi is considered by many to be the unsurpassed pinnacle of the art of animation. Supervising animators Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas wrote in their 1990 book-length account of the creation of Bambi: “Of all the great pictures Walt Disney made, this was his favorite. It is ours, too.” As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of this beautifully wrought film, let’s follow Bambi through a forest full of fun facts about this unforgettable film.

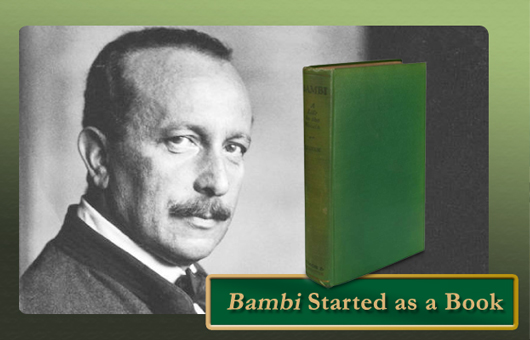

Walt’s fifth animated feature is based on the novel Bambi: A Life in the Woods by Austrian writer Felix Salten, the pen name of Siegmund Salzmann. First published in German in 1923, Bambi was first published in English in 1928 and became a best-selling selection of the Book of the Month Club. “When I read the [Salten] book,” Walt later recalled, “I got excited about the possibilities about animals, what we could do with them.” Walt turned again to the writings of Salten in 1957 when he released Perri. Based on another Salten story, this Bambi-like live-action feature used real animals to tell the fictional “true-life fantasy” of a little pine squirrel. Released just a few years later, the wacky and most un-Bambi-like comedy, The Shaggy Dog (1959), was based loosely (very loosely) on another Salten book, The Hound of Florence.

MGM filmmaker Sidney Franklin purchased the screen rights to the Bambi novel in 1933, but soon realized a live-action film with an all-animal cast would be too challenging to achieve. Believing that only the artistry of Disney animation could fully bring this gentle story to life, Franklin contacted Walt in 1935 to encourage him to make the film instead. Franklin, Walt later said, “was one of our top producer/directors in the business and a man I respected very much. He was a perfectionist. Sidney insisted that we really get the story worked out. It was Sidney who played a big part in really moving us up a step, I’d say.”

Even after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) was completed, Walt discovered that he had not yet developed the art of animation to the point where his artists could create a film as poetic and sophisticated as Bambi. “It was a change of pace for us from what we’d been doing. Snow White, Pinocchio, and the others were more the obvious cartoon-type of characters. But with Bambi, there was a need for subtlety in our animation and the need for a more lifelike type of animation. There was a certain awe and respect we had for this classic, Bambi, [so] I decided I’d have to put my artists back in school to learn something you don’t get in the formal art education. This was animal anatomy, and beyond that animal locomotion. So I put them into school and had my artists specially trained for this one picture.”

Sidney Franklin was contracted as a consultant for three-and-a-half years, but thanks to his respect for Walt, he continued to be invloved until Bambi reached the screen in 1942. Upon seeing the completed Bambi, Franklin told Walt, “It was so far beyond what I expected… I think it is really beautiful and one of your best pictures.” In 1946, Franklin released another Bambi-like pet project that was “deer” to his heart: The Yearling, the story of an Everglades boy and his friendship with a fawn. The live-action film starred Gregory Peck, Jane Wyman, and Claude Jarman Jr. as the boy, who received an honorary Academy Award® for his performance. As a tribute to the Hollywood producer who had so much faith in Bambi, Walt included a special dedication in the film’s credits: “To Sidney A. Franklin our sincere appreciation for his inspiring collaboration.”

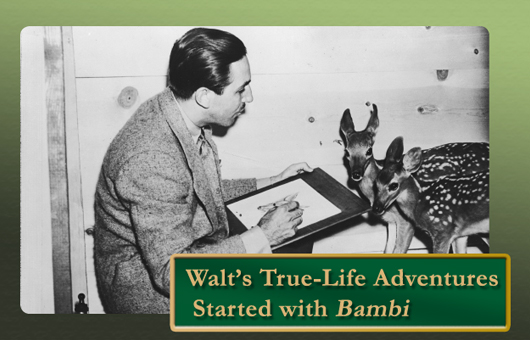

The wildlife denizens of Seal Island, Beaver Valley, and Nature’s Half Acre owe their silver screen fame to Bambi. To assist his artists in creating convincing woodland critters, Walt not only brought in live animals to the Disney Studio for the Bambi animators to study, he also assigned artist and photographer Maurice “Jake” Day in 1938 to take photos of the Maine woods throughout the seasons for reference and inspiration. Day shot approximately 500 black-and-white photos and an equal number of color slides of cloud formations, snowdrifts, tree bark patterns, and many more of nature’s wonders, as well as all kinds of animals. More photos and even motion-picture film was shot by other photographers throughout California, Oregon, and Washington. This incredible film inspired Walt to create his award-winning True-Life Adventures live-action series, for which he commissioned nature photographers to shoot as-it-happened life in the wild. These groundbreaking documentaries debuted in 1948 with Seal Island and ran through 1960, winning eight Oscars® along the way. Bambi sequence director James Algar, who joined Disney in 1934 and was one of the animators of Snow White’s animal friends, was the producer/writer of Walt’s True Life Adventures.

At the time of Bambi‘s production, the artists who would make up Walt’s top team of animators, the legendary Nine Old Men, were coming into their own, and it was to five of the nine that he entrusted Bambi. This hand-selected crew included Milt Kahl, Frank Thomas, and Eric Larson as supervising animators. “Milt and Frank and Eric can get down to these fine points,” Walt said, referring to the exquisite character animation he was championing; Walt later added Ollie Johnston to this elite supervising team. During production, the great impresario also became aware of the talents of Marc Davis. “I worked three years in story on Bambi,” said Marc, who had come to the Disney Studio as an expert animal artist. “I did the stuff of young Bambi, Thumper, and Flower…. Walt decided he wanted to see my drawings on the screen. And so I was to learn to be an animator.” Unfortunately, for all of his Bambi contributions, Marc was mistakenly credited as “Frasier Davis” in the film’s titles; Frasier was Marc’s middle name.

There are only about 950 words of dialogue in Bambi. “We were striving for fewer words,” Walt later said, “because we wanted the action and the music to carry it.” The little dialog involved was acted by a first-rate voice cast, including character actor Will Wright as Friend Owl; Will would go on to play shopkeeper Ben Weaver on the beloved 1960s TV series, The Andy Griffith Show. For the child actors who performed the voices of the young Prince and the other animal youngsters, Walt sought freshness and spontaneity; certainly Donnie Dunagan (who had played the son of Basil Rathbone in the last film of Universal’s excellent but un-Bambi-like monster-movie trilogy, Son of Frankenstein, 1939, and would go on to serve as a United States Marine) delivered as the young Prince of the Forest; and Peter Behn famously delivered an offbeat performance that convinced casting personnel and dialog directors the kid couldn’t act but inspired Thumper’s animators to create a star-making characterization. “Once we got Thumper’s voice,” said Eric Larson, “the character began to work and the animation was built around that recording. We couldn’t have animated it that way if it wasn’t on the recording.”

Interestingly, Mickey Mouse played a role in the performance of Bambi‘s young voice artists when it came time for the child cast to laugh it up. Knowing that laughter is one of the hardest expressions to create on cue, Walt invited the diminutive thespians to a special screening of some of Mickey’s funniest cartoons on the recording stage, and hidden microphones captured their spontaneous laughter. One of the child actors reportedly told Walt, “I’ll work for you anytime, Mr. Disney. This is child’s play.”

Though the characters sing many of the songs in most Disney musicals, it was decided that the forest animals in Bambi wouldn’t warble on-screen, in keeping with the naturalistic style of the animation. The emphasis in this introspective animated feature is on the orchestral underscore. “The way this picture is designed,” said Walt during development, “you’ve got to tell it with music… It will add to the picture’s greatness if you do have a marvelous musical score.” A 40-voice choir sings the film’s lyrical songs and extraordinary choral effects. The score, by Disney veterans Frank Churchill and Edward Plumb, was nominated for an Academy Award®, as was “Love is a Song” as Best Song. (Bambi received another Oscar® nod for Best Sound Recording.)

Bambi also inspired some unusual recordings over the years. In 1957, Roy E. Disney, then working as a Disney wildlife photographer on Perri, was invited to write the dialog for the Disneyland Records label’s (now Walt Disney Records) first film-based Storyteller LP, Story of Bambi. The 1966 LP, Thumper’s Great Race boasted new songs inspired by the original film composed by Disney’s prolific songwriting team of Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman, including “If You Can’t Say Something Nice” and “It’s So Nice On The Ice.”

Did the Young Prince fall down at the motion-picture box office on its first release? Hard to believe, but when Bambi was originally released, this masterwork of animated art failed to find an audience. “It was released during the war,” Walt was to later recall. “And that worked against us. During the war, people were in a different mood, and they didn’t quite go for things like Bambi. But its reissue proved that there’s something in Bambi, I think, that will last a long time.” In 1957, when Disney executive Card Walker reported that the film’s current re-release would bring in two million dollars of pure profit, Walt responded, “I think back to 1942 when we released that picture and there was a war on, and nobody cared much about the love life of a deer… It’s pretty gratifying to know that Bambi finally made it.”

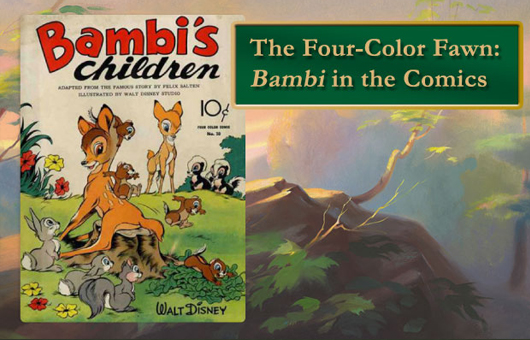

When Bambi was first projected in the nation’s movie houses seven decades ago, it was the dawn of the comic-book industry. The year 1942 saw the publication of a comic-book tie-in (Four Color #12) that was narrated by Friend Owl and drawn by Bambi animator Ken Hultgren. When the movie was re-released in 1947, however, the original 1942 comic was not reprinted; to the confusion of comic-book historians and Bambi fans ever since, an all-new multi-panel adaptation of the film was commissioned (Four Color #186, April 1948), this time exquisitely illustrated by famed comic artist Morris “Mo” Gollub. A nature-lover celebrated for his many painted comic-book covers as well as his actual stories, Gollub had also been a Bambi animator.

Long before the direct-to-video production Bambi II (2006), a sequel based on Felix Salten’s second book, Bambi’s Children, was actually in development after the release of the original film, but ultimately it was never produced. However, Bambi’s Children became a Disney comic book (Four Color #30, October 1943) drawn by Ken Hultgren and featuring the Prince’s fawns, Geno and Gurri.

In 1944, Walt Disney permitted the USDA Forest Service to use Bambi and his woodland friends in a forest-fire prevention campaign pre-dating their famous “Smokey Bear” character. Bambi was featured on a popular poster, proving that the use of an animal figure as a fire-prevention symbol would work. A fawn could not be used in the following campaigns because Bambi had been loaned for only one year, so the Forest Service needed to find an animal that would be the property of the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Campaign, leading to the creation of Smokey Bear. In 2006 and again in 2010, Walt Disney’s little deer returned to appear in new “Protect Our Forest Friends” anti-wildfire Forest Service campaigns.

Even at 70 years old, Walt’s timeless masterpiece is still being honored. In 2011, the Library of Congress added Bambi to the National Film Registry to be preserved as a cultural, artistic, and historical treasure. In its tribute announcing the film’s selection for the Registry, the Library of Congress stated, “This animated coming-of-age tale of a wide-eyed fawn’s life in the forest has enchanted generations. Its realistic characters capture human and animal qualities in the time-honored tradition of folklore and fable, which enhance the movie’s resonating, emotional power.” Seven decades after the young Prince of the Forest first stepped out into the world, Walt Disney’s Bambi still enthralls.