By Jim Fanning

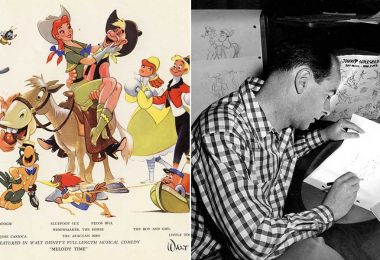

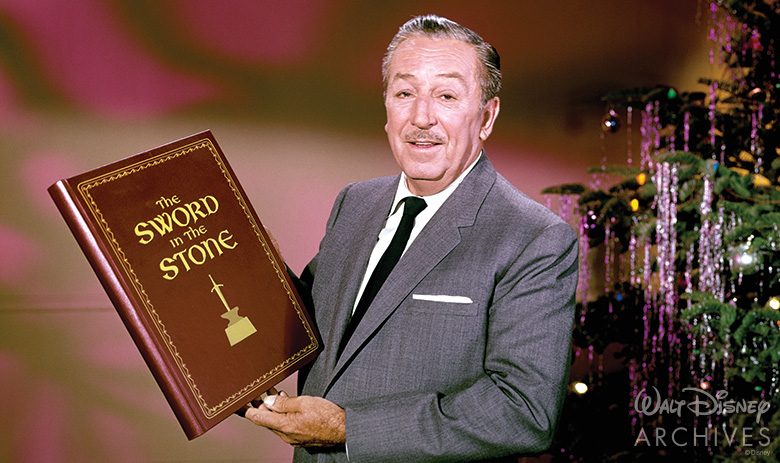

Timeless in its humor, music, and classic Disney animation, The Sword in the Stone ascended the throne in 1963 as Walt Disney’s 18th full-length animated feature. A scrawny 12-year-old boy nicknamed Wart, who is in actuality the future King Arthur, sets ancient England on its ear when the mystical but lovably muddled Merlin—“the incomparable wizard,” as Walt called him—uses wit and wisdom, as well as wizardry, to teach the boy who would be king life lessons that will ultimately lead him extract a mighty sword from an enchanted stone. A sparkling holiday gift for fans of Disney animation, The Sword in the Stone was released on Christmas Day, 1963. Let’s crown our celebration of 55 years of animated enchantment with these royally magical facts.

1. A Legend is Sung of When England Was Young

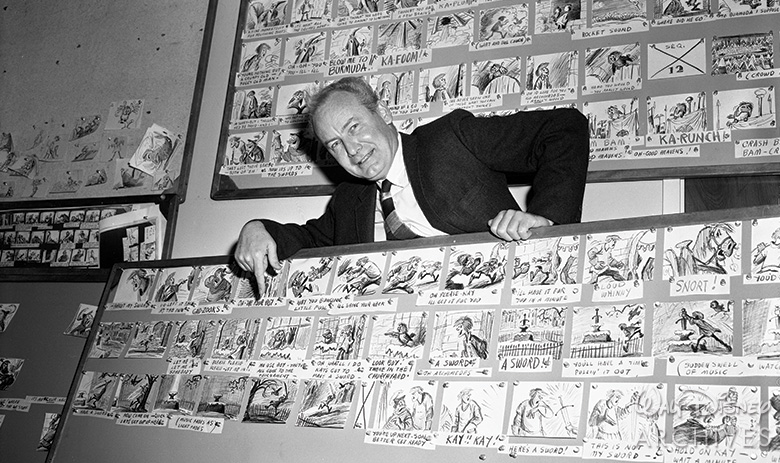

“Our story,” said Walt Disney, ”takes place at a time when England was ruled by might alone. But Merlin can see into the future—in fact, he’s been there—and he knows that a time must come when brains will triumph over brawn. So he sets out to educate the future king in his own peculiar way.” The film is based on T.H. White’s widely read novel The Once and Future King, first published in 1938. Legendary story artist Bill Peet introduced the book to Walt, who obtained the screen rights in 1939. Various attempts were made to develop the story over the years—in 1944 Walt announced that the film was soon to go into production, and story board drawings were created as early as 1949—but two decades would pass before work on the film officially began. Peet knew adapting the complex book would be a challenge. “Getting a more direct story line called for a lot of sifting and sorting,” he revealed. “Walt questioned the first version of my screenplay, pointing out that it should have had more substance. So I made an all-out effort by enlarging on the more dramatic aspects of the story.” Peet remained true to the sophisticated wit of the original, resulting in a humorously told tale contrasting the fifth century with today’s “modern muddle.”

2. Walt Was an Inspiration for Merlin

In adapting the literary work, Peet incorporated Walt Disney—his own personal “wizard”—into the character of Merlin. “Walt the wizard never knew that I patterned Merlin the magician after him when I wrote the script,” Peet later recalled. “In his book, T.H. White describes the wizard as a crusty old curmudgeon, argumentative and temperamental, playful at times, and extremely intelligent. Walt was not a curmudgeon and he had no beard, but he was a grandfather and much more of a character. In my drawings of Merlin, I even borrowed Walt’s nose.”

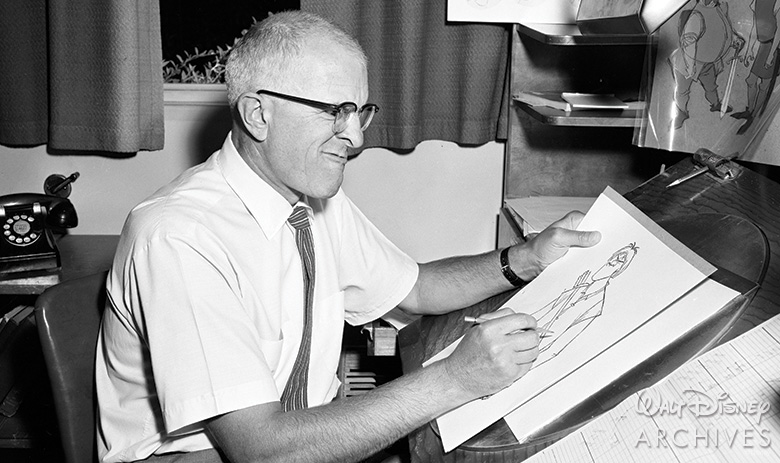

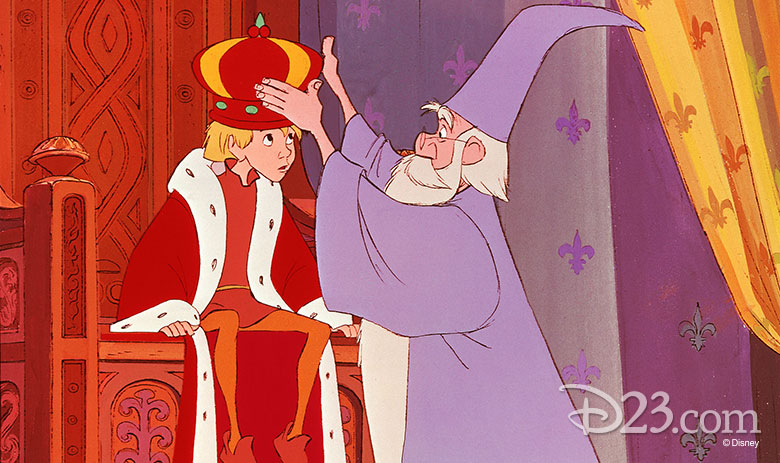

3. Milt Kahl, Master of Magic in Motion

Given the richness of the personalities, The Sword in the Stone was one of master animator Milt Kahl’s favorite projects. “I liked the characters in The Sword in the Stone very much,” said Kahl. “We made Merlin kind of a doddering magician. I thought that’s where he had his charm because he was so bumbling.” Fellow members of Disney’s elite Nine Old Men animation team Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote that Kahl’s “Sir Ector and Sir Kay were the best humans ever done at the studio, as they were done without benefit of live action or the support of reference material.” For the wacky but wicked Madam Mim, Kahl added touches and bits of business that made working on this wild, witchy character a truly enjoyable experience. When The Sword in the Stone director and fellow Nine Old Man Woolie Reitherman saw Kahl’s first rough drawings of Merlin and Mim, he remarked to the animator that they could be displayed in a museum. His response was vintage Kahl: “Aw, you’re full of it!”

4. The Voice of the Wizard

Voicing the role of absentminded Merlin was versatile performer Karl Swenson. Skilled at creating vocal characterizations from his extensive career as an actor during the golden age of radio, Swenson was also in more than 100 television show episodes, and is most well-known for his recurring role as Lars Henson on Little House on the Prairie. The actor returned to the Disney Studios to appear with Ron Howard and Vera Miles in The Wild Country (1971).

5. The Wizard, the Owl, and the Rabbit

Junius Matthews performs the crotchety voice of the educated but irritable owl Archimedes. In addition to many appearances on the Broadway stage and television, this multitalented actor performed hundreds of varied vocal roles on radio. Karl Swenson recommended Matthews to Walt, pointing out the versatile actor had provided the voice of a potato on a radio program. However, he was originally cast as the voice of Merlin, but then switched roles with Swenson and became the voice of Merlin’s owl. Following The Sword in the Stone, Walt cast Matthews as the voice of Rabbit in the Winnie The Pooh featurettes.

6. Laughing it Up with Archimedes

In animating Archimedes, supervising animator Ollie Johnston brought to life one of his all-time favorite scenes of his own animation—the scene of Archimedes convulsed with laughter when Merlin crashes his model airplane. Johnston and Frank Thomas later wrote that Junius Matthews “sustained this infectious laugh for over 20 seconds without at any time letting it feel forced or insincere. By the final scene, both the actor and the owl were completely exhausted, and Archimedes only could point feebly at Merlin and finally slide to the floor where he rolled and gasped for air. Merlin, who had bickered with Archimedes throughout the picture, could think of no way to retaliate other than to puff on his pipe and look very irritated.”

7. A Magical Menagerie

Animals play an important part in the film’s mostly human world, for as Walt explained, “With his wizard’s magic, Merlin changes the boy into a fish, then a bird, and [a squirrel]… always very small creatures so that his survival will depend on brains and not brawn.” Transforming into animals is at the center of one of Disney’s most brilliantly animated sequences. “Storyman Bill Peet gave us the wizard’s duel,” reported Thompson and Johnston, “a perfect use of animation, maintaining personalities through a surprising change in forms and exciting action.” In this fast-paced skirmish of wizardly wits, Merlin and the underhanded Mim try to outwit each other by transforming themselves into a series of unexpected animals. The animators created 15 different visual personae for the battling magicians, with each creature maintaining the personality, visual characteristics, and even color scheme of either Merlin or Mim.

8. Three Voices, One Wart

The voice of the story’s young hero was Rickie Sorensen—a talented teenager who appeared in many classic TV series of the time, including Hazel and The Danny Thomas Show. When the young actor’s voice changed over the three-year production time of the film, director Reitherman drafted his own sons Richard and Robert to complete the vocal role of Wart.

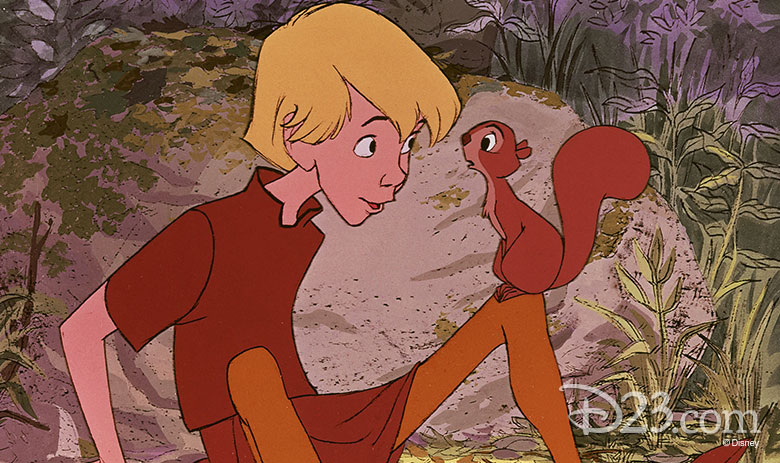

9. Boy Meets Girl Squirrel

In one of the most unusual sequences in Disney animation, Merlin changes himself and Wart into squirrels where a lovely little girl squirrel falls for Wart, unaware that in reality he’s a human. The sequence was originally to focus on the squirrels trying to avoid the hungry wolf who is seen at different points in the film. But the performance of the actress providing the chattering voice of the female squirrel changed Frank Thomas’s entire concept for the scene. Thanks to her charming vocalization, Thomas transformed the sequence into a bittersweet encounter for animator, characters, and audience. When Walt saw Frank’s animation he suggested that a Granny Squirrel be added to pursue Merlin. Thomas was so fond of the squirrel sequence, it was screened at his memorial service after he passed away in 2004.

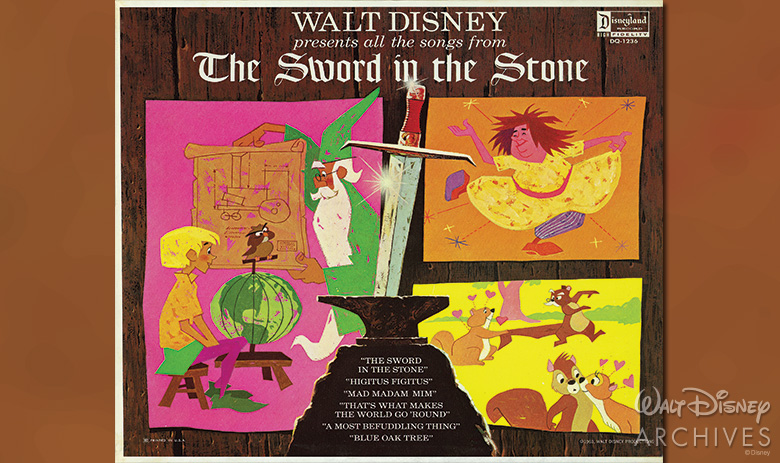

10. Sword, Sorcery, and Sherman Songs

The Sword in the Stone was the first animated feature to include songs by Disney’s newly signed songwriters, Richard and Robert Sherman. “We enjoyed it immensely,” said Robert Sherman of conjuring up six songs for the magical motion picture, “because with animated films the songs seem so much more important to the entire story line of the film.” For example, “A Most Befuddling Thing” is Merlin’s way of explaining the mysterious force of love in the squirrel sequence. “Higitus Figitus” is one of a long list of Disney songs demonstrating Walt’s love of coined words, in this case Merlin’s magic sayings. “We didn’t want to say ‘Abracadabra,’ we just wanted to do different words,” explained Richard Sherman, “and so the conversation was he’s British, and we have to have sort of a British-sounding magic, and also it’s sort of Latin, because he’s very into Latin and Greek.” The Shermans’ songs helped composer George Bruns receive a 1964 Best Score Oscar® nomination for his inspired Sword in the Stone musical score.