By William Keck

“To our friend Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul, we will be forever grateful.”

This dedication in the closing credits of Beauty and the Beast pays homage to the film’s lyricist, Howard Ashman, who never lived to see the final print. Were only real life as just and compassionate as the wonderful world of Disney, where a kiss can wake a sleeping princess and an evil enchantress’ curse can be broken just as the final rose pedal falls.

For Ashman, there was no miraculous last-minute reprieve. The Oscar©-winner passed away due to complications from AIDS in March 1991 at age 40—eight months before his masterpiece was unveiled to the world.

Even so, there were miracles. That Ashman was somehow able to conjure such life-affirming lyrics while privately waging a fight to survive in an era of great fear, ignorance, and prejudice is nothing short of remarkable. Those who worked with Ashman believe his private frustrations and struggles found their way into the film’s characters—most recognizably within the Beast.

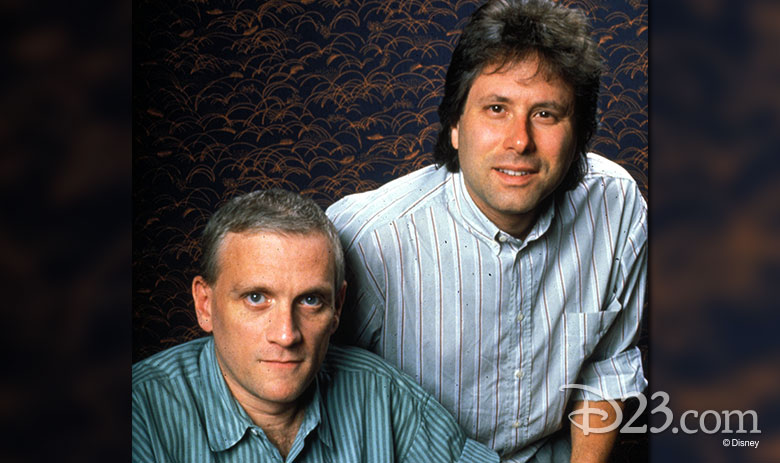

“It was Howard who really shifted the focus to make it about the Beast,” explains Tom Schumacher, former president of Walt Disney Feature Animation, now president and producer for Disney Theatrical Group. “That the Beast has made a tragic mistake [and is] looking for redemption… that was constructed by a man who at that time in the AIDS crisis knew he wasn’t going to get out.”

“A lot of that found its way into the heart of this movie,” agrees Ashman’s collaborator, composer Alan Menken. “And I think in some ways that came out in lyrics.”

After the film’s release, legendary CBS anchorman Dan Rather—in an article written for The Los Angeles Times, drew a comparison between the AIDS crisis and the cursed Beast’s knowledge that his chance to be human again was ticking away. Said Rather, “You feel the Beast’s loneliness and desperation a little more deeply. He’s just a guy trying as hard as he can to find a little meaning, a little love, a little beauty, while he’s still got a little life left.”

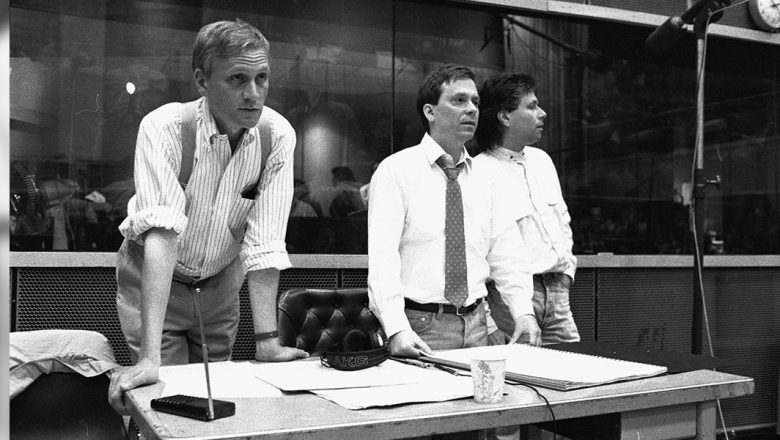

Because of Ashman’s failing health, he opted to stay put near his doctors in his hometown of Fishkill, New York—about 60 miles north of New York City, meaning the rest of the creative team had to be flown in to work on his turf. “We weren’t quite sure why we were doing it, to be really honest,” recalls the film’s producer, Don Hahn. “We thought, ‘Well maybe Howard’s just being a diva and he just won an Oscar, so let’s go out to work with him.’”

Hahn set up his team at a no-frills Residence Inn and furnished an upstairs conference room with a rented piano. “The Residence Inn there, which is nothing special, is the place where this whole movie came together,” Hahn adds. “Howard would bring donuts in and we would sit down and just spend day after day kind of slogging through the story.”

Hahn finds it both odd and endearing when die-hard Beauty fans let him know they’ve made visits to Fishkill—and that very Residence Inn. “I say, ‘You’ve got to be kidding?’ It’s like one of those kind of Disney pilgrimages for super fans to go visit.”

Ashman did manage to muster enough strength to come alive during the cast recording sessions. “He was able to be with us for [awhile] in the studio, directing us, high energy, I mean amazing energy,” recalls Paige O’Hara, who gave voice to Belle. “Howard could do anything. There were a couple scenes, I don’t think I was nailing it, you know. And at one point he said, ‘Well do it like this,’ and all of a sudden he transformed into Belle. He could do the Beast or any character.”

During O’Hara’s final recording session with Ashman, he told her to “put a little Barbra Streisand” into her playful take on “Something There”—the last song he wrote for the film. She spoke with Ashman once more by phone at Menken’s home when the composer was teaching her to sing the film’s title song. “I was getting ready to do the press tour singing “Beauty and the Beast,” because Angela (Lansbury) didn’t want to sing it; she said, ‘I’d rather Paige do it’,” recalls O’Hara. “So Alan had me over to his house and he taught me ‘Beauty and the Beast’. I sang through it and he said, ‘We have to call Howard… He hasn’t really heard anyone singing it other than me at this point.’ So we call him on the phone and I sang ‘Beauty and the Beast’ to him, and he’s like, ‘Oh honey, it sounds so good. You sound so beautiful.’ And I hang up the phone and I looked at Alan and said, ‘I just got this really strange feeling.’ And he said, ‘I did, too.’ And it turned out that was the last time I ever spoke to Howard.”

Ashman never heard the applause at the test screenings, from the blown-away critics at the New York Film Festival, or at the film’s Florida premiere screening, where O’Hara was seated near Menken and his family. Much of O’Hara’s thoughts that night were focused on the man who wasn’t there. She remembers looking over at Menken and noticing he, too, was in tears.

Were O’Hara to have her own wish granted, she says she would thank Ashman for “all that you’ve done. You brought animation and musicals back to Disney. They’re going to affect children’s lives forever. But the truth is he was the film. He saw it in his heart and in his mind. It was his vision, and I think he knew exactly how it came out.”