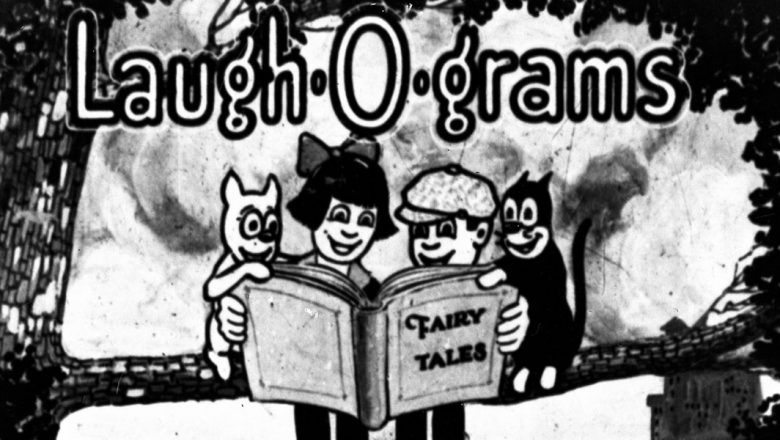

Before the Alice Comedies, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and Mickey Mouse, Walt Disney produced one-minute shorts, known as the Newman Laugh‑O‑grams, for the local Newman cinema chain in Kansas City. He then went on to open his first animation studio and create a series of six modernized fairy-tale shorts, known as the Laugh‑O‑grams.

“I started, actually, to make my first animated cartoon in 1920. Of course, they were very crude things then, and I used sort of little puppet things.” —Walt Disney

During his time in Kansas City, Walt Disney produced the Newman Laugh‑O‑grams for a local cinema. The Newman Laugh‑O‑grams were very short subjects, lasting less than a minute, and dealt with topical local issues. Few of these “Lafflets” survive.

The following video provides an assortment of clips from those first Newman Laugh‑O‑grams.

More substantial were the six Laugh‑O‑grams that followed in 1922. These can really be regarded as Walt’s first entries into the realm of the animated short. They were The Four Musicians of Bremen, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, Jack and the Beanstalk, Goldie Locks and the Three Bears, and Cinderella. All of them were retellings of the original stories, updated and drastically changed. They cannot be described as good cartoons, but they can certainly be said to “show promise.” There is an unusual attention to detail in them, as for example in Puss in Boots where the individual members of the crowd at a bullfight are animated. These shorts are marred, however, by repetitiveness—every good gag is repeated several times over, until it stops being a good gag. Critics claimed this was laziness on the part of the Laugh‑O‑gram company (and later the Disney company)—that they were using the same animation several times over in order to bump the shorts up to length—but Walt explained that the repetitions were for humorous effect. Significantly, the practice ceased.

Of the characters in three of these shorts, we know nothing except that there was a Jack with a beanstalk, a Goldie Locks with three bears, and a girl with a red riding hood. If there are any prints still extant, they are not known to the Disney Archives. Of Cinderella we know a bit more. Her only friend is a cat. The role of the Fairy Godmother is not to turn a pumpkin into a coach but a garbage can into a Tin Lizzie; the cat drives Cinderella in this to the Prince’s ball. Walt was to return to the subject more seriously several decades later.

Viewing The Four Musicians of Bremen and Puss in Boots, however, gives us a fair impression of the way the characters were treated in the other four Laugh‑O‑grams.

In The Four Musicians of Bremen, the central character is a little black cat—one is tempted to think of him as Julius in an earlier incarnation, especially when he displays the ability to pull off his tail and use it as a baseball bat. (This cat uses the tail to knock away incoming cannonballs.)

The other three musicians are a dog, a donkey, and a chicken. They are blamed for everything that goes wrong in town and chased out. They pause for a rest by a pond and realize that they are hungry (hunger is personified as a demon with a pitchfork that he stabs at the relevant stomach). The cat has an idea: if they play their instruments, they might charm a fish from the pond to dance to the music. This plan is successful, to an extent. A fish does indeed emerge from the water but, in his attempts to catch it, the cat falls into the pond, where a swordfish pursues him. In fact, he is pursued right back out of the water and, with his companions, up a tree that the swordfish proceeds to saw down. The four musicians fall down through a chimney into a house full of robbers, who dash out and start attacking the house with cannons. This is where the cat uses his tail as a baseball bat; later, having hitched a lift aboard a flying cannonball, he uses the tail also to belabor the robbers. He falls off his cannonball in due course and loses all nine of his lives; however, he manages to catch hold of the last one just in the nick of time and survive—as do the other three musicians, so that all four of them can live happily ever after.

Clearly the tale has little by way of coherent plot—it is essentially a good excuse for a series of visual gags. The same can be said of Puss in Boots, the third of the Laugh‑O‑gram shorts to be released. Just as the rest, Puss in Boots depends for its gags on extensive digressions from the main plot and the frequent use of repeated segments of action. It has little in common with the traditional tale.

At any level, Puss in Boots is a fairly primitive piece of work—as were the other Disney shorts of the Laugh‑O‑gram years (and, in fairness, the shorts being produced by everyone else at the time). The animation is somewhat rudimentary and the characterization nonexistent, the plot is as rickety as a perpetual‑motion machine and rather less convincing, and as we have noted, any gag that looks as if it might have some remote chance of being funny is forthwith repeated several times in order to hammer that chance into oblivion. In terms of plot and gags, in fact, the overall feeling one gets from the movie is that it is the work of immature minds—which of course it is. As in any other sphere of the creative arts, it is unfair to criticize a great artist on the grounds of the work produced in his adolescence—and Walt, at age 20, was at the time of this film’s production still barely more than an adolescent.

However, the movie is of some importance in the development of the Disney oeuvre for one reason: the character of Puss in Boots himself. Like the cat in The Four Musicians of Bremen, he forms an essential stage in the evolution of what would prove to be Disney’s first major cartoon‑character creation: that of Julius. The big difference between the two is not so much a physical one (the two are quite similar in appearance) as one of characterization, because at some stage in the years between 1922 and 1924, Disney learned the art of giving his characters that most elusive quality of all: personality.