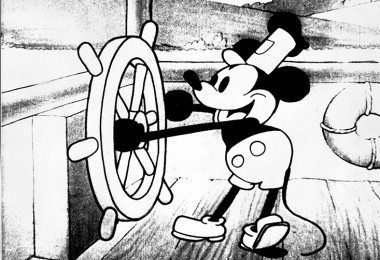

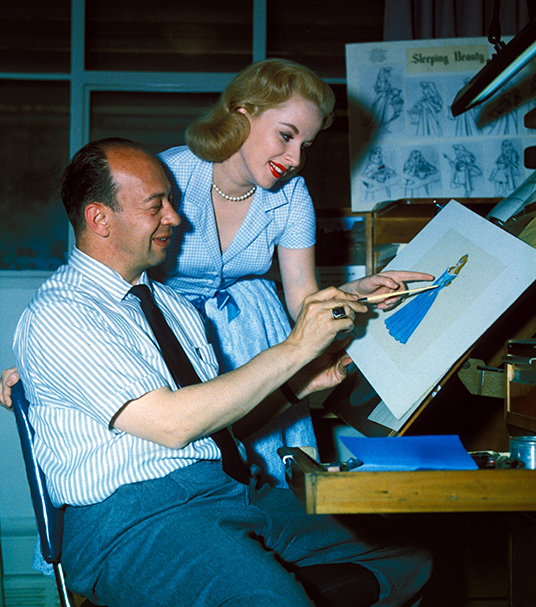

Several years after the maestro of the animation world skillfully blended art and classical music to create Fantasia, Walt Disney looked to classical music again as he planned a new animated feature, Sleeping Beauty. His selection of 22-year-old Mary Costa as the voice of Princess Aurora matched Peter Tchaikovsky’s beloved classical music with a voice destined to grace the world’s most renowned opera houses.

This Disney Legend still marvels at how her career was impacted by creative guidance from two of the 20th century’s most gifted geniuses

As it would turn out, Walt’s fateful casting of Mary Costa helped accelerate her fame. The singer’s early success ironically helped bring her to the attention of one of the world’s greatest composers, one whose work had been included in Fantasia years earlier. Hollywood is filled with unusual stories of life-changing encounters, and this Disney Legend still marvels at how her career was impacted by creative guidance from two of the 20th century’s most gifted geniuses.

More than 50 years after the release of Sleeping Beauty, Mary regards working with Walt on the animated classic as one of the positive influences on her decision to pursue opera. “Walt wasn’t really a musician, but he respected and admired people who made music their art,” she recalls.

As a result of the publicity generated by the movie, Mary saw her Disney work open doors to film and television appearances. As she voiced Briar Rose singing about her dreams of finding true love, Mary dreamed of an opera career. She knew a transition from popular entertainment into the more “serious” opera world was considered difficult to achieve. As production on Sleeping Beauty finished, Walt gave her some advice when she shared her ambitious goals one day at the studio.

If you apply the ‘Four Ds’—dreams, dedication, determination, and the discipline—you can make it

“An opera career is quite a desire,” he told her. “But if you apply the ‘Four Ds’—dreams, dedication, determination, and the discipline—you can make it.”

She took Walt’s alliterative principles to heart, and by the time Sleeping Beauty opened in 1959, Mary had launched a stellar career, including an early Hollywood Bowl appearance that would ultimately lead her to add more than three dozen operas to her performing repertoire. Just as Tchaikovsky’s music had brought her to Walt, Mary’s foray into opera was about to connect her to another Russian composer whose work had also been associated with Disney.

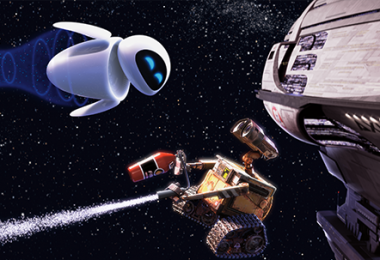

When Walt famously set classical compositions to animation for Fantasia, Igor Stravinsky was the only composer still living to see his work on the big screen. Born in Russia in 1882, Stravinsky was a boy when he saw Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty ballet during its premiere year in St. Petersburg. Stravinsky grew up intending to become a lawyer, but music lessons led him into a new career. Regarded as one of the early 20th century’s greatest composers, by the late 1930s he had moved to Hollywood where he often conducted concerts at the Hollywood Bowl. In 1940, Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was included in Fantasia, and the rest is Disney history. It’s a connection not lost on Mary Costa.

Walt Disney was fascinated by The Sleeping Beauty ballet, and so was Igor Stravinsky

“Walt Disney was fascinated by The Sleeping Beauty ballet, and so was Igor Stravinsky,” she notes. Not too long after the release of Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, Stravinsky heard a Mary Costa recording from her first Hollywood Bowl appearance.

Mary was appearing with the San Francisco Opera when she was told that Stravinsky had personally requested her to sing the role of “Anne Trulove” in the company’s first production of The Rake’s Progress, an opera completed in 1951 as one of the composer’s last great works.

“As exciting as that was, imagine the thrill when I was told that Stravinsky wanted to coach me himself for the role at his home in Los Angeles,” the singer recalls.

Then 80 years old, Stravinsky invited Mary to spend three weeks with him for private vocal coaching and intensive rehearsals. The idea of working directly with the composer himself was a little daunting, so Mary first worked with famed conductor Fritz Zweig, a protégé of another great composer, Richard Strauss. “I practically knew it backwards by the time Stravinsky was ready for me,” she says with a laugh.

He loved to make me laugh . . .

Accompanied by Zweig on the piano, Mary sang for Stravinsky in his studio. Although Stravinsky enjoyed a reputation for perfectionism that some artists found intimidating, Mary thought he had an incredible sense of humor. “He loved to make me laugh,” she says.

She even saw Stravinsky’s sensitive side during her three weeks with him. “He was remarkably knowledgeable about a singer’s voice. Like Walt Disney, he was intuitive about guiding my performance. Where Walt had coached me to think of singing like painting with a vocal palette, Stravinsky told me to keep up my energy level and to never ever let it drop, even during the softest phrases of my singing.”

Stravinsky was remarkably generous in that he encouraged me to take breaths where I needed them

With a challenging aria early in Act I of The Rake’s Progress, Mary viewed the role as one of the toughest in her young operatic career. “Singing of that caliber required being in top physical shape because of the energy a body needs to sustain that level of live performance,” she says. “Stravinsky was remarkably generous in that he encouraged me to take breaths where I needed them, even though we had the score right in front of us with his original suggestions marked to tell the singers when to breathe.”

To Mary’s relief, Stravinsky was pleased with her interpretation of the role, especially when she opened to critical acclaim in The Rake’s Progress. “He could be a very tough taskmaster, but he knew I was prepared and would do his work justice. He attended the performance and told me he thought it was perfect. That’s one of the great memories of my life.”

Prior to the production in San Francisco, she even joined Stravinsky and his wife for other performances of the composer’s work in Seattle during the Century 21 Exposition (1962’s Seattle World’s Fair). In Vancouver, she attended a performance of The Firebird, Stravinsky’s 1910 composition later adapted in Disney’s Fantasia/2000.

“I sat with his wife at that performance and she said, ‘Oh, Igor has grown to hate The Firebird if it’s not performed correctly. It just upsets him so.’ Off she went backstage to calm him down and make sure he wasn’t too upset. I thought it was just funny to see him fret about which of his compositions were better than the others, but I think that critical level of thinking just demonstrates greatness.”

Mary’s work with Stravinsky represents one of the legendary facets of a career that flourished throughout the 1960s, from her work with Leonard Bernstein in the London premiere of Candide to her 1964 debut in La Traviata at the Metropolitan Opera. In just a few short years, Costa realized the dreams she had shared with Walt Disney and became a respected soprano known for her devotion to the opera. With her movie and television background, she was frequently in demand as a guest on television variety shows where she made opera accessible to audiences.

Her reputation as an artist led to an invitation by Roy O. Disney to serve as one of the founding members on the Board of Directors at the California Institute of the Arts, the college established by Walt Disney in 1961. During her time on the board, the college hosted a benefit premiere of Walt’s last live-action film, The Happiest Millionaire (1967).

Walt wanted a combination of a classical and popular sound, and in many regards, my career always bridged those two worlds . . .

“I remember attending a CalArts function where Roy O. Disney and I had a lovely visit together, and he told me that Walt knew within five or six notes of my audition that my voice possessed the qualities he wanted for Sleeping Beauty. Walt wanted a combination of a classical and popular sound, and in many regards, my career always bridged those two worlds. I think that was true of Disney’s and Stravinsky’s work, too.”

In 2004, Mary returned to the Hollywood Bowl as a narrator in a musical extravaganza that featured a tribute to iconic Disney music. That evening, she couldn’t help but think back to her own history at the Hollywood Bowl, including the recording of the performance that led her to Igor Stravinsky just a few years after working for Walt Disney.

“As a singer, I rarely looked back,” she says. “I always looked ahead to the next project or the next concert, so only in recent years have I stopped sometimes to think about the wonder of how so many parts of my life are related to each other. In many ways, I think Sleeping Beauty was a kind of continuation of Fantasia, so how blessed I was to work with both Disney and Stravinsky in two different aspects of my career.”

Since her retirement from the opera, Mary set out to share lessons she learned from her show business experience and working with the likes of Disney and Stravinsky. She actively supports arts education and regularly visits schoolchildren to encourage them to explore their creative talents. In 2003, the U.S. Senate confirmed her presidential appointment to the National Council of the Arts.

In recognition of her contribution to the arts, the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville voted earlier this year to award her an honorary degree at its May 2013 commencement ceremony. The degree marks the third one she’s received in her life. Dr. Costa has mentored scores of young performers at the university’s School of Music and passed on much of what she learned from some of the creative geniuses who nurtured her own career.

“I learned the same principles from Walt Disney and Igor Stravinsky,” she shares. “Any music is serious if you’re serious about it, be it opera or popular music. That’s why I advise people to find their own voice when they sing. Never try to copy someone else. Be an original.”