By Jim Fanning

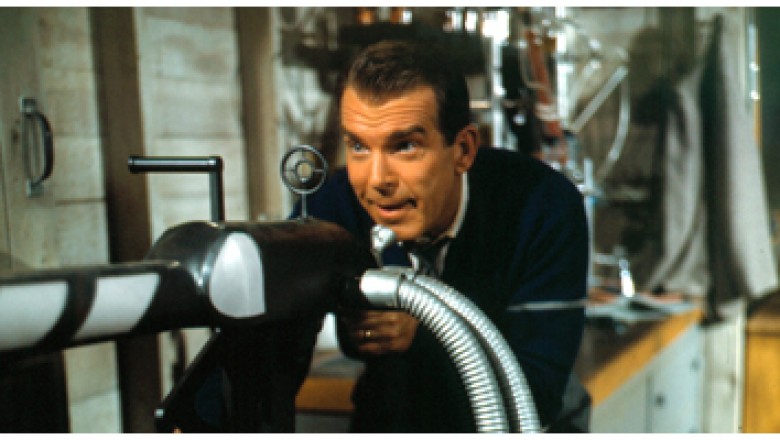

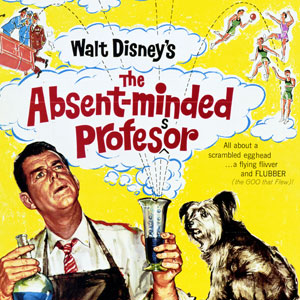

Familiar with the smash-hit, glowingly reviewed, and Oscar®-nominated film that’s set on a college campus? It’s where a revolutionary new invention gets the whole university bouncing. No, we’re not talking about 2010’s The Social Network. The above accolades reference The Absent-Minded Professor (1961). Walt Disney’s enormously popular funfest of a film. Starring Fred MacMurray, the first Disney Legend inducted in 1987, this kooky collegiate comedy relates the story of Medfield College’s Professor Ned Brainard, who is so preoccupied with his scientific experiments that he’s forgotten to show up at his own wedding three times — the latest time because he’s discovers an anti-gravity material, “flying rubber” or flubber. “The goo that flew” enables Prof. Brainard to take wing in his Model T Ford, allow the scrawny Medfield basketball team to slam-dunk their way to victory, and turn Washington, D.C.’s heavy world of bureaucracy upside down. Originally released on March 16, 1961, this zany film is one of Walt Disney’s most revered family comedy hits.

One story was about rubber and one was about flying cars, and we combined them.

So how did this weird goo known as flubber first bounce into the hearts of moviegoers everywhere? Well, after the overwhelming success of Walt Disney’s The Shaggy Dog (1959), the studios were inspired to search for another zany “shaggy dog” story. And there couldn’t have been a better way to follow up with their last fantasy comedy hit about a man who transforms into a dog than with one about an “absent-minded professor” who invents a new wacky substance. Walt had obtained the screen rights to the short stories published in Liberty magazine by Samuel Taylor about an eccentric professor and his inventions. “One was about rubber and one was about flying cars,” recalls writer-associate producer Bill Walsh, “and we combined them.” Bill adapted the screenplay with veteran Disney artist Don DaGradi as a sequence consultant. “Walt thought Don could develop my ideas into pictures, but Don turned out to be a great story man himself,” Bill says. Walt made Don a full-fledged screenwriter and he and Bill Walsh co-wrote many other Disney films, including Mary Poppins.

We put aluminum fenders on it and of course took out the engine.

The Absent-Minded Professor enabled Walt to indulge one of his great joys: creating cartoon-like antics in a live-action film. The iconic image from this classic comedy is of course Prof. Brainard’s flying flubber-powered flivver. The airborne-automobile effects were accomplished utilizing a number of techniques, including the sodium screen matte process, miniatures and wire-supported mock-ups. For the wirework, the Model T was refurbished to make it as light as possible. “We put aluminum fenders on it and of course took out the engine,” reveals Disney’s legendary second-unit director Arthur J. Vitarelli, who helmed the special effects sequence for many Disney special-effects extravaganzas starting with The Shaggy Dog. “We made a fiberglass crankcase, the wheels with foam rubber tires, a screen for the radiator, and a fake differential out of fiberglass,” he says. Today, Prof. Brainard’s Model-T is part of the collection at the Walt Disney Archives.

Flying past the Washington Monument, looking through the little windows at the top, was great fun.

Special permission had to be obtained to fly a helicopter down the Mall between the Capitol Building and the Washington Monument. With the help of famed stunt pilot Paul Mantz, authorization was granted to Walt Disney, even though the sky-borne camera team was ordered to maintain a strict and very specific altitude.

To make the scenes where Ned and Betsy wing their way above Washington in the Model-T believable, special effects artist extraordinaire Peter Ellenshaw was dispatched to Washington, D.C. to shoot airborne footage of the nation’s capitol. Not surprisingly, special permission had to be obtained to fly a helicopter down the Mall between the Capitol Building and the Washington Monument. With the help of famed stunt pilot Paul Mantz, authorization was granted to Walt Disney, even though the sky-borne camera team was ordered to maintain a strict and very specific altitude. “The right-hand door of the helicopter was removed, a tripod was fixed so that the camera was hanging over the edge, the cameraman sat with his feet dangling outside,” Peter later recalled. “Flying past the Washington Monument, looking through the little windows at the top, was great fun.”

The show-stopping, eye-popping basketball game, which has the Medfield b-ball team bouncing high over the heads of their Rutland College rivals, was born out of the need to crate something that could visually dramatize flubber. “Walt said, ‘Maybe we’re overlooking something… sports,'” reported Bill Walsh of the great showman’s bouncing-basketball-players brainstorm. “No other studio was doing movies relating to sports but Walt saw that this was perfect for our kind of audience: kids, teenagers, the family.” The flubberized basketball game almost didn’t get past the jump ball, however. At first, no one could figure out how to get Don DaGradi’s fast-paced sight gags on the screen. But Bill Walsh turned to Art Vitarelli, who then, working with special-effects artist Bob Mattey, virtually invented the art of flying with actors on piano wires. He thought up the harness that fits under the costume and allowed the performer a great deal of natural movement. “Up to that time,” explained Art. “There was only one wire in the back — and you were really limited in what you could do because your body wanted to fall forward.” Pre-production for the complex game of airborne hoops alone took two months and two weeks to shoot. “Every shot was a whole scene of choreography,” explained Art. “So you planned ahead. You had every shot planned.”

Can you guys write me a college fight song? Something real collegiate?

Richard and Robert Sherman, new members of the Disney team, wrote songs for The Parent Trap (1961), but had come on board too late to contribute their talents to The Absent-Minded Professor. Late in production, Bill Walsh, whose office was across the hall from the songwriting siblings asked, “Can you guys write me a college fight song? Something real collegiate?” The result was the “Medfield Fight Song” — the first Sherman Brothers song heard in a Disney feature (The Parent Trap was released later that year). The Shermans also wrote a zingy novelty tune titled “Flubber Song,” recorded by Fred MacMurray, and another song came about when technical advisor Professor Julius Sumner Miller (Professor Wonderful on the 1960s syndicated version of Mickey Mouse Club) explained “serendipity” as setting up a climate where things can happen logically. “Walt was fascinated with the word,” recalled Bill Walsh. “And he had the Shermans write a song about it.” Fred MacMurray performed “Serendipity” on TV’s Walt Disney Presents on March 26, 1961 and re-broadcast in Man in Flight which was modified to promote The Absent-Minded Professor.

Besides the music, another iconic Absent-Minded Professor sound that fans most vividly recall is the distinctive noise made by flubber as it gives flight to the Model-T. “Flubber defies gravity and its sound defies description,” said Bill Walsh. “In a word, the sound of flubber was produced by several secret thicknesses of laminated plastic cut in triangular form and agitated in a peculiar manner on a variable tape recorder. In our quest for this unique sound, we tried oscillators, theremins, and all kinds of strange electronic equipment. Flubber not only had to emit a new sound but one with charm, and a soaring, spiritual quality. We rubbed everything together that we could rub together, or play backward, forward or sideways at all possible speeds. We tried two- or three-thousand sonic effects. It took a year to find the perfect sound, which is about as long as it took to cast Scarlett O’Hara.” Peter Ellenshaw had a Eureka! moment when he happened to absent-mindedly (appropriately) swing a plastic T-square back and forth. Hearing the wobbly sound it made, Peter knew he “heard” flubber, and that plastic-produced noise became the basis of the unforgettable flubber sound.

It either gets played or banned.

The Sherman Brothers incorporated the sound-sational effect into their “Flubber Theme” and the hilarious novelty tune was a favorite of kids, teens, and college students. “So far the “Flubber Theme” [of the 45 rpm single] has provoked great controversy,” reported Jimmy Johnson to distributors of records — on the Disneyland label (now known as Walt Disney Records) — just weeks into Absent-Minded Professor’s release. “There seems to be no in-between view,” he says. “It either gets played or banned. On those stations where the latter occurs, “Serendipity” [the B side of the record], which is the art of having a happy accident — we might accidentally have a hit!”

One of Walt’s favorite actors, Fred MacMurray, is comic perfection as the befuddled professor. “I have taken a back seat all my film career,” joked Fred during production. “Kids and shaggy sheepdogs have been my nemesis but never before have I been upstaged by a bucket of bolts. She’s Walt Disney’s flying hot rod, a car with a personality.” Fred recalled that, on the set of The Shaggy Dog, Walt told the actor of having seen Prof. Hubert Alyea, professor of chemistry at Princeton University demonstrate at the International Science Pavilion of the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. For The Absent-Minded Professor, Walt invited Prof. Alyea to the Studios to give a demonstration for Fred, who incorporated some of Alyea’s characteristics into his performance.

Nobody ever asked me!

Nancy Olson, so appealing as housemaid Nancy in Pollyanna (1960), plays Betsy Carlisle, Ned’s long-suffering fiancée. Disney favorite Tommy Kirk, who Walt called his “good-luck kid,” is Biff Hawk, Medfield’s basketball star forced to sit out the big game by flunking Brainard’s science class. One of the most unusual bits of casting came in the tiny form of 74-year-old Belle Montrose as Prof. Brainard’s dedicated housekeeper. Walt Disney saw Belle performing her vaudeville act on Steve Allen’s variety TV hour it just so happened that Belle was the real-life mother of Mr. Allen — and added her to the cast. When inquiries came about why she had never before acted in a movie, she replied, “Nobody ever asked me!”

A collection of character actors adds zest to the zaniness, including Disney favorite Wally Boag as a TV reporter (Wally also did the stunt dancing for Fred MacMurray), while frequent Disney voice artist Candy Candido is seen as the hot-dog vendor. Also on hand are the two flubber-gasted cops, Forrest Lewis and James Westerfield, who were such a hit in The Shaggy Dog. The film even reunited the screen comedy team of Wally Brown and Gordon Jones, who play the basketball coaches. The referee is Alan Carney, Brown’s former partner in the comedy team of Brown and Carney.

In his first Disney role, Keenan Wynn is villainously perfect as greedy Alonzo Hawk, but there is more than one Wynn on hand. Keenan’s then-19-year-old-son Ned has an unbilled cameo as the dance-mad college lad, while Keenan’s father and Ned’s grandfather, famed comedian and radio, TV and movie actor Ed Wynn, also pops up in another cameo as the fire chief (a wink at Ed’s popular 1930s radio show The Fire Chief). This was the first Disney live-action film for Ed Wynn but not the last. Walt Disney cast the Oscar©nominated (for Best Supporting Actor, The Diary of Anne Frank, 1959) in many other live-action films, most notably Mary Poppins.

Nineteen star athletes were signed for the film’s whacky sports scenes. The eleven collegiate football players who tackle flubberized Alonzo Hawk include the famed McKeever twins, Mike and Marlin, of USC. For the zany basketball game, eight star college players were recruited. Added to the cast were Gordon Martin and Mike Fryer of USC and Carroll Adams of UCLA. Carroll Adams was a coach at a Southern California high school at the time of filming. These experienced players portrayed the Rutland team; professional dancers played the flubber-fueled Medfield team. Popular assistant USC coach Bob Kopf was the technical advisor for the fastest moving basketball game ever seen.

Heading for a Riot of Fun at the Chinese Theatre with The Absent-Minded Professor

For the opening of the film at Hollywood’s legendary Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in March 1961, forty-five members of the Model-T Car Club of Southern California drove their “tin lizzies” (each adorned with a banner proclaiming “Heading for a Riot of Fun at the Chinese Theatre with The Absent-Minded Professor” as they headed down Hollywood Boulevard to arrive at the film’s opening.

The film was enthusiastically reviewed, but more importantly, audiences absolutely flocked to this wacky funfest. The Absent-Minded Professor appealed to audiences of all ages, just as Walt knew it would. It played an astonishing seven weeks at Radio City Music Hall, where it was the Easter attraction, and it was honored with three Oscar® nominations (Best Cinematography — Black-and-White, Art Director — Black-and-White and Best Special Effects). The main cast comically reconvened for a sequel, Son of Flubber (1963), which brought more fun with Prof. Brainard, the flying car and the anti-gravity goo, too. So iconic is this comedic classic that it inspired a TV movie follow-up and a new version Flubber (1997), starring Robin Williams, which actually credits Bill Walsh as a screenwriter and features a cameo by Nancy Olson.