Film Historian and Author J.B. Kaufman (Pinocchio: The Making of the Disney Epic) makes the Dog Days of Summer a little cooler with his look back at the making of the 1949 short Pluto’s Sweater.

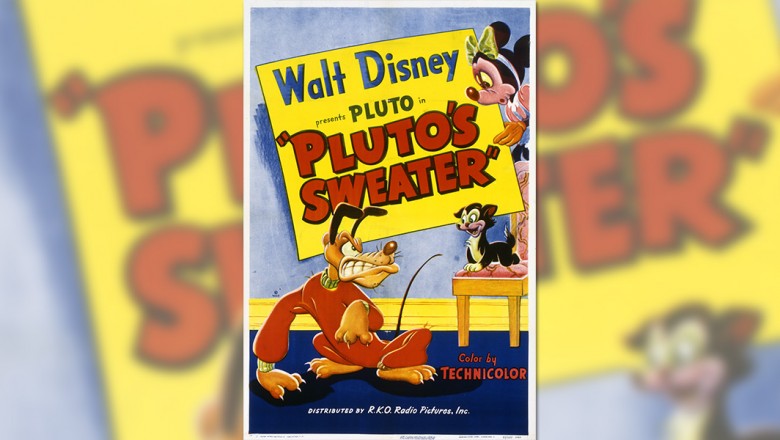

Recently, in the course of some other research, I made an interesting Pluto discovery. Pluto’s Sweater (1949), one of dozens of Pluto shorts released during the 1940s, was, I found, unusually well-documented in the Walt Disney Archives and Animation Research Library. By the late ’40s the Pluto production unit was headed by director Charles Nichols, a former animator. Working with his regular staff of artists, Nichols turned out Pluto shorts on schedule as a consistent, reliable product line. The resulting cartoons are not among the celebrated Disney classics; in fact, Disney fans tend to look upon them with little regard (although one of them was nominated for an Academy Award®).

But that very obscurity makes the late-1940s Plutos more interesting in another way. The postwar years are a pivotal period in Disney history, a breathless pause between the turbulence of the war years and a new surge of activity in the 1950s. Walt, restless to try something new, was venturing into live-action production and other unfamiliar territories. Meanwhile, the Shorts units were continuing to crank out one-reel cartoons featuring the familiar Disney characters—perhaps with reduced personal involvement by Walt himself, but aware that they were providing the studio’s bread and butter. Thanks to the wealth of documentation of Pluto’s Sweater, we can gain an insight into the workings of this overlooked branch of the Disney studio during these years.

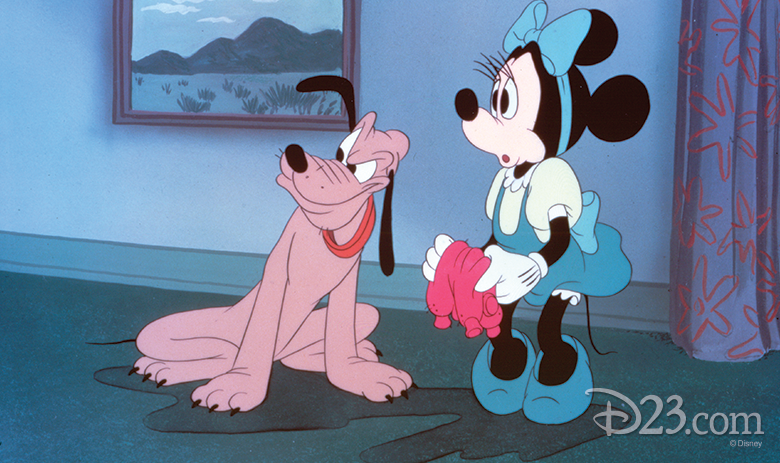

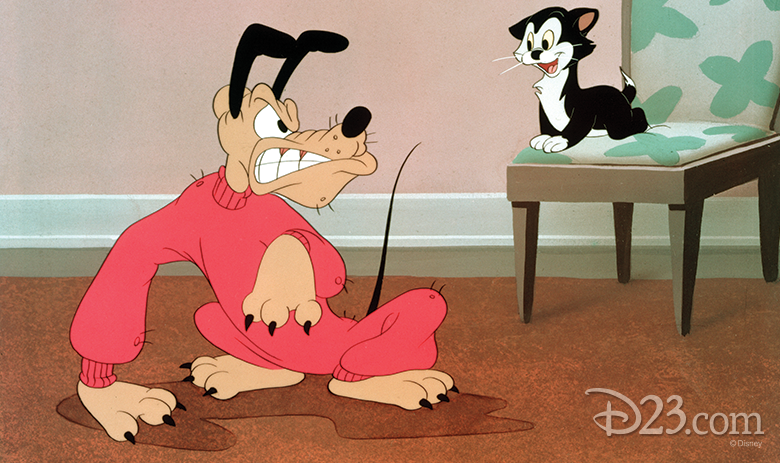

The story of Pluto’s Sweater was the work of Eric Gurney and Milt Schaffer, two story artists of long experience. During the spring of 1947 they developed their outline: Minnie Mouse knits a sweater for Pluto, to keep him warm outside in cold weather. Pluto, mortified at the sight of the sweater, frantically tries to avoid wearing it, while Figaro enjoys his discomfiture. Forced to go outside in the new garment, Pluto tries to extricate himself from it and, in the process, falls in water. The sweater, now soaking wet, begins to shrink and becomes much too small for Pluto—but is now perfectly suited to Figaro.

By the end of April 1947, unit secretary Dorothy Link could report to production supervisor Ken Peterson that this story had been broken down into scenes and handed out to the animators. Allowing for some turnover, Nichols maintained a consistent crew of animators in the Pluto unit during these years. In casting them for Pluto’s Sweater, he assigned the more “character-driven” scenes—Pluto and Figaro ridiculing the sweater, Pluto’s horror when he realizes the sweater is intended for him, Minnie in tears—to Phil Duncan, while George Nicholas, Hugh Fraser, and George Kreisl took the more action-oriented scenes. Most of Pluto’s outdoor scenes, attempting to free himself from the sweater, were divided between Fraser and Kreisl. Duncan and Nicholas, between them, animated all of Minnie’s and Figaro’s scenes; Nicholas also animated the brief appearance of the gang of dogs who spot Pluto wearing the sweater and laugh at him.

The artists set to work quickly, and within a week’s time, in early May 1947, Nichols was viewing some of their rough pencil animation in sweatbox. He issued sweatbox notes to them, asking for minor changes in their animation. Even at this early stage of production, Nichols focused on details: Duncan was asked to draw Figaro in one scene with his “eyes … about 3/4 closed with just a little of the pupil showing in the final pose”; Nicholas, in animating another scene, was asked to “take out the devilish expression and just have Figaro smiling at the end.” Nichols is sometimes criticized today for the blandness of the cartoons he directed, but in fact, in writing these sweatbox notes, he pushed for stronger action. Critiquing the scene in which Minnie pushes Pluto, in his new sweater, toward the door, director Nichols told animator Nicholas that “This scene should be much more definite,” urging broader, more violent action for both characters.

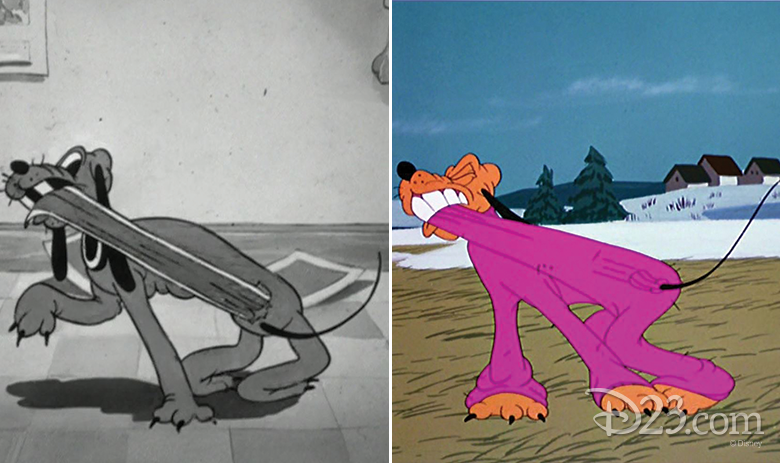

In animating their scenes, these artists didn’t hesitate to make use of all the resources of the Disney studio. During one of the exterior scenes in this short—scene 43, Pluto attempting to pull the sweater loose with his teeth—the alert Disney fan may spot a brief snippet of action that looks familiar. In the midst of this scene, animator Hugh Fraser cannily borrowed a short passage from the legendary “Flypaper Sequence”—animated by Norm Ferguson nearly fifteen years earlier for the classic short Playful Pluto.

During the spring and early summer of 1947, in between his work on other shorts simultaneously in production, Nichols continued to review the animators’ work on Pluto’s Sweater and to tinker with other details. In mid-May, Dorothy Link sent a detailed two-page memo to editor Hal Burns, enumerating the film’s sound effects. Most of these sounds were drawn from the studio’s extensive library of prerecorded sound effects; but for Pluto’s scenes outdoors, Link noted, “We recorded some running, soft thumps and runs where Pluto is in sweater—accent when he hits ground.”

Thanks to the wealth of documentation of Pluto’s Sweater, we can gain an insight into the workings of this overlooked branch of the Disney studio during these years.

By early July, Nichols was satisfied with the animators’ “ruffs.” Now he okayed all the scenes for cleanup, moving from the rough generality of the animators’ original sketches to the polished precision of the “cleaned-up” drawings which would be traced onto cels. Still maintaining his eye for detail, Nichols cautioned the cleanup artists to maintain a consistent appearance for the sweater in the early scenes, making it “look like a ski suit on Pluto—baggy legs with tight cuffs, etc.”

The cleanup animators began to return their finished assignments to Nichols, and now he started the review process over again—this time viewing the cleaned-up pencil scenes and approving them, one by one, to be sent to the inkers. From October 1947 into early 1948, the review continued. As before, Nichols viewed the scenes with a critical eye, approving most of them without comment but occasionally calling for a correction: fixing an unwanted jump in the action here, a registration problem there. By the first week in February 1948, all the scenes had been approved.

Even after this extended, painstaking effort during production, one more hurdle remained. Early in March 1948 the decision was made to cut out a major quantity of Minnie Mouse’s dialogue. Minnie’s lines had been recorded nearly a year earlier and had been part of the soundtrack ever since. The records don’t tell us whether these cuts were called for by Walt himself or by someone else, but for whatever reason, Minnie became much less talkative in the spring of 1948.

Most of these cuts involved off-screen dialogue, and so were relatively simple matters of sound editing. In scene 15, for example, the camera saw Pluto and Figaro attempting to hide under the sofa while Minnie, in another room, called “Oh Pluto, here, boy!” Eliminating her follow-up line, “I have a wonderful surprise for you,” called for no changes in the animation. However, scene 56, a close-up of Minnie reading a book, had originally shown her reading out loud. When this idea was dropped, the scene was retrieved from Ink and Paint so that Phil Duncan could reanimate it, eliminating Minnie’s mouth movement.

With these changes in place, the short was finally completed. The finished scenes went to the camera department in mid-March 1948. After a short round of retakes, the final negative was assembled, and Pluto’s Sweater took its place in the Disney schedule of releases. The studio registered it with a copyright date of 18 May 1948, but, in fact, the official release date was nearly a year later, at the end of April 1949. Today Pluto’s Sweater is little remarked upon—but when we consider how many shorts the studio released during these years, and that each one of them received a similar level of care and attention, we can gain a fresh perspective on this little-remembered chapter of Disney animation history.