By Alexander Rannie

Few moments in animation linger in the mind as vividly as the ballroom sequence in Beauty and the Beast. The seamless combination of music (“Beauty and the Beast,” sung by Angela Lansbury as Mrs. Potts), hand-drawn animation (Mrs. Potts, Chip, Lumiere, Cogsworth, Belle and the Beast), and computer technology (the ballroom environment) leaves an indelible mark on the viewer; both Belle and the Beast’s deepest emotions are revealed, though neither says a word. It’s filmmaking at its finest and is but one of many reasons Beauty and the Beast was nominated by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for Best Picture of 1991.

25 years after its release, Beauty and the Beast and its remarkable ballroom remain “ever a surprise.”

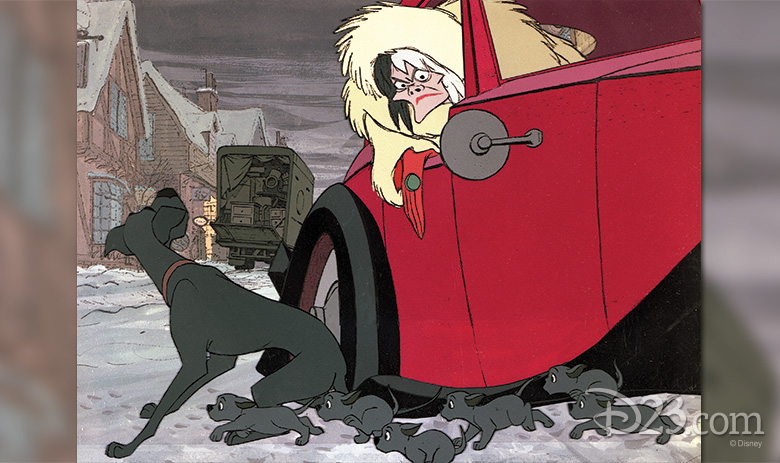

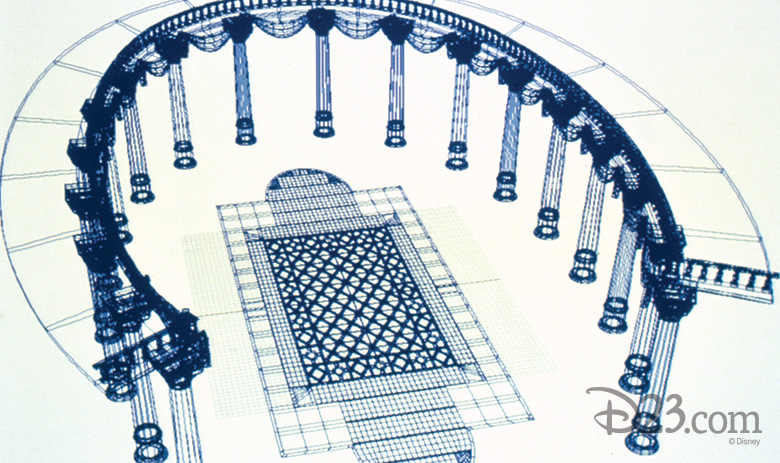

A key component of the ballroom sequence was its unprecedented use of computer-generated imagery (CGI) to create the magnificent splendor of the marble ballroom. Though the ballroom is on screen for less than a minute-and-a-half, its impact is such that we remember the scene lasting much longer, a fact quickly latched onto by Disney marketing which made the ballroom a touchstone image in promoting the film.

Walt Disney was always looking for opportunities to incorporate new technologies into his creations. He convincingly added sound, color, and dimensionality to the vocabulary of animation. With Fantasia (1940) he presented multi-channel audio reproduction, dubbed Fantasound, which allowed the music of The Philadelphia Orchestra to swirl around the theater in choreographic synchronization with the action on the screen. For conveyances as diverse as Stromboli’s carriage in Pinocchio (1940) to Cruella de Vil’s Duesenberg in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) live-action models were photographed on film, with the resulting images combined with character animation and transferred to cels, anticipating computer animated vehicles to come in films such as Oliver and Company (1981), The Prince and the Pauper (1990), and Rescuers Down Under (1990). To this day, Feature Animation continues to explore new frontiers in technology and how they might better serve the storyteller’s art.

By the time of Beauty and the Beast Disney animators were looking for the opportunity to create a completely computer-generated environment, rendered entirely within a computer, in which they could place hand-drawn heroes, heroines, and villians. (They were no doubt encouraged and challenged by the groundbreaking all-CG shorts being produced and directed by John Lasseter at a new company christened PIXAR.) Several fortuitous events led to a breakthrough on Beauty and the Beast.

Prior to the making of Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), shooting live-action footage that was intended to have animation added to it meant that the opportunity for sweeping camera moves ranged from limited to non-existent. Most of the time the live-action camera was locked down to insure a stable scene in which animated characters could interact with their human counterparts. But when it came time to shoot the live-action footage for Roger Rabbit, animation director Richard Williams told director Robert Zemeckis to move the camera however he liked and it would be up to the animators to match the onscreen action. Though this resulted in what was often an arduous task for the animators, the final product was so thoroughly convincing that it raised the bar for all combination animation/live-action films to come. It also opened the door for previously untried ways of staging camera moves in animation.

At this same time, Roy E. Disney’s encouragement of new technologies in animation helped usher in the development of the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS). Begun at Lucasfilm and completed at PIXAR, CAPS made cels and animation cameras obsolete. Using CAPS, animators’ drawings could be scanned, painted digitally, and then digitally combined with scans of hand-painted backgrounds. Whereas Disney’s 1937 multiplane camera—used to create the illusion of depth—allowed for only five layers of artwork, the levels and size of artwork that could be combined in CAPS were near infinite. An additional advantage to CAPS was that hand-drawn animation could be combined with a computer-generated environment entirely in the digital realm, thereby negating the need for an optical printer (and its generational loss—rather like a photocopy of a photocopy), a film-based image compositing device in use since the 1920s.

During early production meetings for Beauty and the Beast discussions of how and where computer-generated environments might be incorporated resulted in two possibilities. The first was the forest surrounding the Beast’s castle. Experiments in constructing CG trees proved that the technology simply wasn’t there yet to create a convincing forest that felt of an organic part with the overall look and atmosphere of the film. The second possibility, posed by story supervisor Roger Allers and story artist Brenda Chapman, was to fabricate an entirely computer-generated ballroom for the sequence containing the song “Beauty and the Beast.” This felicitous idea worked well for several reasons.

Because the filmmakers acknowledged that the look of a CG ballroom would be different from the rest of the film, they felt that the idea of it being bookended—Belle and the Beast enter, and then leave this unique world—would help ease audiences into and out of the computer-generated space. And because of the success of Roger Rabbit’s animators in working with fluid camera moves, the development of CAPS, and the almost limitless possibilities of camera movements available in the realm of a CG environment, Allers and Chapman approached the storyboards for the ballroom sequence with few constraints.

The otherness of the ballroom also worked well with the heightened emotional moment that takes place during Mrs. Potts’ rendition of lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken’s song “Beauty and the Beast.” Though no words are spoken between them, Belle and the Beast are finally able to communicate their deep and abiding love for one another. (In Howard Ashman’s early notes outlining the characters in Beauty and the Beast he compared the Beast to Yul Brynner as the King of Siam in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I. In this musical the two leads, the King of Siam and schoolteacher Anna Leonowens, discover how much they care for one another in the show-stopping polka “Shall We Dance?” Though “Beauty and the Beast” is a slow ballad, not a brisk polka, the tradition of falling in love while dancing remains a tried and true one.)

In traditional animation a pencil test is made of an animator’s rough drawings to assess the success of a scene before the it is cleaned up, inked, and painted. In computer animation a vector test, or wire-frame test similarly allows a scene to be assessed in bare bones outlines before being redone or fully rendered. In order to guide animator James Baxter, who would animate Belle and the Beast, two proxy figures were incorporated into the wire-frame test, with Belle resembling a nothing so much as a bishop from a Staunton chess set, and the Beast looking like an oversized gourd (acquiring the nickname “watermelon man”). Once the camera moves were approved, the wire-frame test was printed onto animation paper as a guide for Baxter, who began animating the two lead characters. Producer Don Hahn has commented more than once on how Baxter’s brain had a computer-like ability to figure out how to animate Belle and the Beast in a constantly-changing perspective. Even the animation in the remarkable high-angle down shot of J. Worthington Foulfellow, Gideon, and Pinocchio in the song “An Actor’s Life for Me” in Pinocchio pales by comparison to the constantly shifting sightlines presented to Baxter. While Baxter toiled away with his challenge, the CGI department worked to fully develop the skin of marble, wood, gold, and material that would turn the ballroom into a three-dimensional reality.

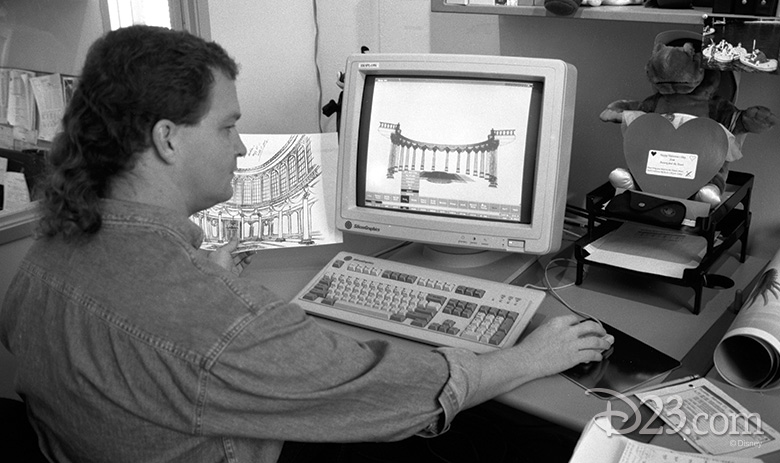

Drawing inspiration from a painting by background artist Doug Ball, and art director Brian McEntee’s regal color scheme of gold and blue, Scott F. Johnston, working with Jim Hillin, M.J. Turner, and Tom Cardone, built the ballroom using, among other software, RenderMan®, newly developed by PIXAR. Every detail was attended to, from the candles on the wall, to the marble floor, to the crystals hanging from the chandelier, to the lion faces atop the columns, and the blue bunting draped about the room. A fresco of cherubs on the ceiling was created by scanning a hand-painted background and then texture mapping it onto the CG dome of the chamber so that it felt like an organic part of the world of the ballroom. As the CG elements began to fall into place a 1K grayscale rough render, with James Baxter’s rough animation of Belle and the Beast, was produced. This was followed by another pass incorporating Baxter’s cleaned up animation. And finally a high-resolution 2K color version was fully rendered. Each frame included multiple elements: the main room, the floor, reflections in the floor, the characters, tones and shadows on the characters, and even the characters’ reflections in the floor. The time it took a computer to render a single frame took from four to six hours. At one point the filmmakers were concerned that the CG ballroom might not be completed in time; their backup plan was to simply have Belle and the Beast dancing in a spotlight, surrounded by darkness. (This was referred to as the Ice Capades version.) Fortunately, the CGI department was able to fully render the sequence in time. One additional element was added in post-production: certain shots contained a slight depth-of-field element, which mimicked a live-action camera lens by throwing the background slightly out-of-focus and causing the animation of Belle and the Beast to “pop.” The overall effect contributed to Allers and Chapman’s original idea to give the ballroom sequence more of a live-action feel. The ballroom was constructed over the course of two years, with the majority of the work done in the final nine months.

As Scott F. Johnston said, “Howard Ashman and Alan Menken set it up, Angela Lansbury knocked it out of the park, and we just needed to do them justice; we had to rise to their level of excellence.” They definitely did and 25 years after its release, Beauty and the Beast and its remarkable ballroom remain “ever a surprise.”

Special thanks to Don Hahn, Scott F. Johnston, John Carnochan, and Larry Leker.