By Jim Fanning

Who holds the world’s record for winning more Academy Awards® than anyone else? Steven Spielberg? Meryl Streep? Frank Capra? Though those leading Hollywood lights are Oscar® winners all, the record holder is Walt Disney with 32 Academy Awards. Setting high standards for excellence, Walt exemplified the quality the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has sought to honor since that august organization presented its first Awards in 1929. In celebration of this year’s Oscars, presented March 7 on ABC, let’s shine the klieg light on some of Walt Disney’s dazzling Academy Award highlights.

By the time the category of Best Short Subject (cartoon and live-action) was added for the 1931-32 Academy Awards, Walt Disney was the critical and audience pleasing favorite of Hollywood. In fact, the Academy created the category specifically to honor Walt and his achievements in animated artistry. When the Oscars were presented on November 18, 1932, Walt was the recipient of the Best Short Subject: Cartoon award for Flowers and Trees (1932), part of his artistically unprecedented Silly Symphonies series. In addition, Walt was awarded a special Oscar for creating what even the biggest name in Hollywood would admit was filmdom’s brightest star Mickey Mouse. For the glamorous ceremonies on that big night, Walt had produced a special Mouse cartoon, in which Mickey appeared in color for the very first time. Entitled Mickey’s Parade of Nominees, this unique Disney production presented the acting candidates in the fun-filled form of animated caricatures designed by Disney Legend Joe Grant, at the end of which Mickey piped, “I’m sorry. I can’t come any further so I’ll have to ask Mr. Disney to accept my prize for me.” At this point Walt received his honorary Oscar, only the second Special Award given to an individual in the Academy’s five-year history (the first such Special Award was given in 1929 to Walt’s idol, Charlie Chaplin for The Circus, 1928). Mickey was nominated that year too, for Mickey’s Orphans (1932), but would not appear in an Oscar-winning film until Lend a Paw (1941).

To make the whole thing even more of a “Hollywood story” Walt played a significant role in Oscar lore. The word famous golden statuette, revered as the superlative symbol of cinematic excellence, is today well known as the Oscar. Though there is some question about exactly how the Academy Award ended up with that unlikely moniker (the most accepted reason is that Academy librarian Margaret Herrick thought the statuette resembled her Uncle Oscar), there is no doubt who popularized the nickname. At the Academy Awards presentation held on March 16, 1934, Walt accepted the Best Short Subject: Cartoon Academy Award for the wildly popular Three Little Pigs (1933). In his acceptance speech, Walt referred to the award as “the Oscar,” a nickname heretofore regarded as a derogatory term. As famed Hollywood screenwriter and journalist Frances Marion reported, “When Walt referred to the ‘Oscar’ in his speech, that name took on a different meaning, now that we had heard it spoken with sincere appreciation.”

It seems only appropriate that Walt’s Silly Symphonies won more Oscars than any other cartoon series until the late 1940s. From 1932 through 1939, the Silly Symphonies won the Oscar every year (including Ferdinand the Bull, 1938, released as a Special but originally planned as a Silly Symphony). Other Disney cartoons also earned Oscar gold including Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953). The night that the stylish animated short — the first ever to be produced in widescreen CinemaScope® — garnered Hollywood’s highest honor, Walt’s Oscar quota soared as he also collected three other Oscars for the True-Life Adventure Bear Country (Two-Reel Live-Action Short Subject), the People and Places short The Alaskan Eskimo (Documentary: Short Subjects) and The Living Desert (Documentary: Features), the latter two awards presented by filmland’s legendary Elizabeth Taylor. Both the True-Life Adventures and the People and Places films racked up Oscars for Disney, demonstrating the great showman’s versatility in filmmaking, vividly visualized by the sight of Walt proudly posing with his armload of Oscars.

The crowning Oscar glory for Walt was undoubtedly Mary Poppins (1964). This critically acclaimed, incredibly popular musical fantasy was honored with an astounding, near-record 13 Academy Award nominations, more than any of Walt’s other films had received. For the first time ever a Walt Disney film was nominated in most of the major categories, including Best Actress (Julie Andrews), Best Screenplay Based on Material From Another Medium (Bill Walsh and Don DaGradi) based on the books by P.L. Travers, Best Color Cinematography (Edward Colman), Best Director (Robert Stevenson) and Best Picture. On Oscar night, April 5, 1965, the film flew off with five gleaming statuettes, again a record for a Disney film. The main competition for Walt’s “fair lady” was the movie version of My Fair Lady (1964), which managed to waltz off with most of the major honors, including Best Director and Best Picture. Since that night, some critics and historians have wondered if the Academy wouldn’t have been wiser to have rewarded Mary Poppins with the awards in the major categories as it was a completely original work for the screen as opposed to My Fair Lady, which despite its excellence, is a film of a fully realized Broadway show.

After the Academy Awards ceremony, Julie Andrews wrote to Walt: “I just wish with all my heart that we had bagged an Oscar for ‘best film’ too! It so deserved it.” “Knowing Hollywood, I never had any hope that the picture would get it,” responded Walt. “As a matter of fact, Disney has never actually been part of Hollywood, you know. I think they refer to us as being in the cornfield in Burbank.”

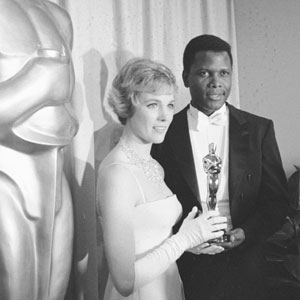

Surprising as it may seem now, Walt was thought to be going out on an artistic and financial limb casting Julie as the lead in this major production as no other Hollywood producer was interested in this Broadway star as a silver screen viability (Jack Warner famously passed over Andrews in favor of Audrey Hepburn as Eliza in My Fair Lady, the role Julie created on Broadway). In accepting the Oscar for her motion picture debut — an accomplishment achieved by few film performers — Julie made the practically perfect statement, “I know where to start — Mr. Walt Disney gets the biggest thank you.” Also winning that night were those supercalifragilisticexpialidocious songwriters Richard and Robert Sherman who received Oscars for Best Song (“Chim Chim Cher-ee”) and Best Score, receiving the former from Fred Astaire and the latter from Debbie Reynolds.

A few years later, the Sherman Brothers reunited with fellow Oscar honorees director Stevenson and co-writers Walsh and DaGradi for Bedknobs and Broomsticks, a film that had been in development under Walt since before Mary Poppins was produced. Nominated for five Academy Awards, the musical fantasy swept away with the statuette for Best Special Effects, a testament to the Oscar-worthy talent of Walt Disney and his filmmaking magicians.

Today, Walt’s Oscar legacy continues to live on as some of his most well-loved animated characters have appeared at the Academy Award ceremonies as presenters, usually for Best Short Subject, including Snow White (cutely quipping, “I’ve got more than a little experience with short subjects”) in 1993 and Mickey Mouse in 2006. The extraordinary filmmakers behind such contemporary animated classics as Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Up (2009) — the first animated features in Academy Award history to be nominated as Best Picture — carry on the Disney tradition of excellence that made Walt Disney, most deservedly, the most winning Academy Award-winner ever.