By Jim Fanning

An eventful “Winds-day,” a bothersome rainstorm, a nightmare-full of honey-hungry hallucinations, and the first appearance of a very bouncy buddy—all of these elements combined to help create Walt Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day. A whimsical sequel to Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (1966), Disney’s second visit to the Hundred Acre Wood was even more popular than the first. So break open a new “hunny” pot, watch out for Woozles, and savor nine smackerals of behind-the-scenes celebrating 50 years of blustery fun.

The Pooh-rade Marches On

Although Walt Disney first envisioned his animated adaptation of the books by A.A. Milne as a feature, the savvy showman ultimately felt that American audiences were not sufficiently familiar with the British stories, so he decided to split the burgeoning story into three parts and release each as a separate featurette. With the popularity of Pooh’s initial featurette, Walt looked forward to producing the second, certain it would be an even bigger hit. After Walt’s death in late 1966, Disney executives decided in late summer 1967 that Blustery Day would be the first animated film to be put into production without Walt, and so the new Pooh project commenced under the working title of Winnie the Pooh and the Heffalumps.

Five Nine Old Men Walk Into the Hundred Acre Wood

John Lounsbery and Eric Larson of the legendary team of the Nine Old Men, animated on the first Pooh featurette, which was directed by fellow Nine Old Man Woolie Reitherman. Lounsbery and Reitherman continued in their roles for the next installment, while signing onto a Pooh project for the first time were Ollie Johnston, Frank Thomas, and Milt Kahl. Thomas and Johnston were particularly happy to be on Team Winnie the Pooh as they were fans of the original books and the Ernest H. Shepard illustrations. “I liked the Shepard drawings very much,” said Johnston, “but you have to go with what you can do in animation that requires the characters to do things they don’t have to do in a story illustration.” The animators kept in mind Walt’s edict that Shepard’s illustrative charm be maintained in the featurettes. Said Thomas of the designs in general and Pooh in particular: “If you take a design like that as your model and then get the personality just right, and with all the help of Sterling Holloway’s voice as Pooh, the audience accepts it as being the same as the original design because they’re swayed by the way he moves and the way they thought he should move.”

Tigger Bounces Onto the Scene

For his Disney animation debut, Tigger was animated almost entirely by master Milt Kahl. Though the first Pooh book, Winnie-the-Pooh, was published in 1926, Tigger was not introduced until the second book, The House at Pooh Corner, was issued in 1928. The hyper tiger was inspired by a new addition to son Christopher Robin’s menagerie of stuffed toys, but Milne based the manic personality of Tigger on Chum, a Spaniel who was always jumping onto people and just about everything, causing all kinds of chaos for his owners. Walt had considered Disneyland Park performer Wally Boag for Tigger’s voice, but ventriloquist-actor Paul Winchell was ultimately cast as the voice of the trouncy, flouncy tiger. “Paul did a great job, his voice was full of life,” said Johnston. “His vocal performance really inspired Milt to get that real brisk timing into Tigger.” The bouncy critter’s famed so-long statement, “TTFN—ta-ta for now” was ad-libbed by Winchell.

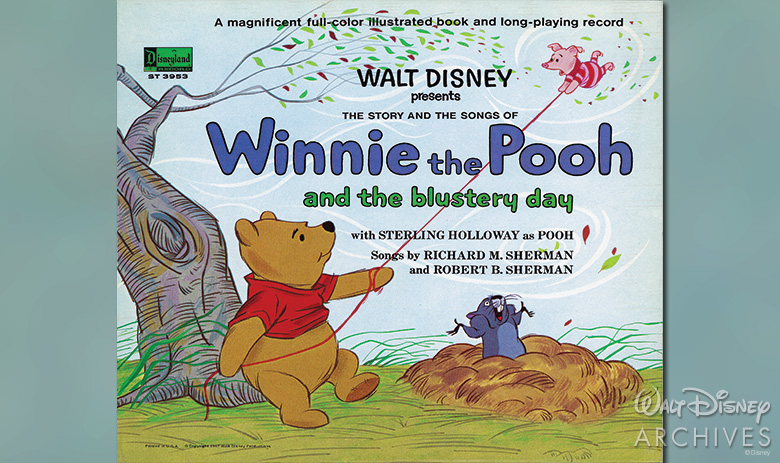

Tigger Sings with a Spring

One of the most wonderful things about Tigger is his upbeat signature tune. “We wrote a song about Tigger which exemplifies exactly what he did,” said Richard Sherman about the Sherman brothers song “The Wonderful Thing About Tiggers.” “It was a fun song to write, especially that last line: ‘The most wonderful thing about Tiggers is I’m the only one.’” Though sung with infectious gusto by Paul Winchell in Blustery Day—and heard on some of the Pooh record albums as performed by Sam Edwards—the second verse of the Shermans’ “Tigger” song was never performed onscreen until The Tigger Movie (2000).

Milne or Sherman OR Gilbert and Sullivan?

The songwriting team of Richard and Robert Sherman composed the five songs heard in Blustery Day during 1963 and 1964, along with the other Winnie the Pooh songs. Said Richard: “The books are so charming and so filled with whimsy. We wanted to get that feel in our songs—that if Milne had written a song, he most likely would have written it that way. We wanted it to be Milnesque but it needed to be Disney, too. For the sequence featuring Pooh and Piglet swept away by the flood, we wanted a Gilbert and Sullivan quality. That’s very British and very apropos. So we had the words repeating—‘the rain, rain, rain came down, down, down’—a whole sequence of pure singing [by a chorus] with pictures. And the animators loved it.”

Trespassers William Would be Proud

Tigger wasn’t the only new character to join the cuddly citizens of Christopher Robin’s “enchanted neighborhood” in this new Pooh film. Pooh Bear’s very good and very timid friend Piglet swept onto the scene, sweeping leaves and being swept into the sky by the blustery wind. “To take something like a little rag doll, which is Piglet, and try to give him enough acting that communicates with the audience was a real challenge,” said Frank Thomas. The Disney animators gave Shepard’s Piglet design a rounder face complete with cheeks that could express emotion in animated movement. Piglet’s endearingly hesitant voice was performed by John Fiedler, perhaps most famous as one of the poker players in The Odd Couple (1968) and as Mr. Peterson, one of Bob’s patients, on The Bob Newhart Show. Fiedler performed the voice of Piglet longer than any of the other members of the original Pooh cast. His last performances as the very small animal included Piglet’s Big Movie (2003) and Pooh’s Heffalump Movie, released in 2005, the year this prolific, piglet-like character actor passed on.

They’re In, They’re Out, They’re All About!

Along with Piglet and Tigger, some imaginary honey-hoggers showed up, too. In the Milne original, the Heffalumps and Woozles were not described or shown (except one Shepard illustration of an elephant haunting Piglet’s dream), so the filmmakers had free reign to creatively convey these silly yet scary creatures dreamed up by Pooh. In composing the “Heffalumps and Woozles” song, Robert Sherman remembered that “there were no rules, really, so we could do whatever we wanted to do.“ Explained Richard Sherman: “We very much wanted to do kind of a fun, spooky kind of a thing. Heffalumps and Woozles were a wonderful concept of Milne’s. We loved the play on words.“ The Shermans’ imaginative song inspired Disney animators to new heights of surrealistic creativity in visualizing Pooh’s wild nightmare. “It’s an outstanding sequence,“ observed Richard Sherman.

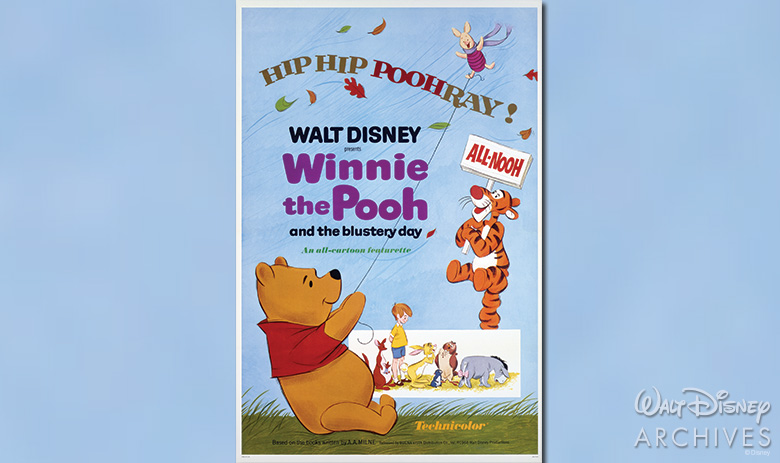

Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day Blows Into Theaters

In anticipation of Pooh skipping back to the screen, Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty proclaimed October 25, 1968, as “Winnie the Pooh Day.” Direct from Disneyland Park, Pooh and his pals made personal appearances at Sears stores in 25 U.S. cities to tie in with its famous line of exclusive Pooh clothing and merchandise that began with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree. In each of the cities lucky enough to have Pooh visit, including Seattle, St. Louis, Atlanta, Buffalo, Boston, and Washington, D.C.—the bear of very little brain and company arrived via the Disney company plane to attend tea parties and fashion shows, appear on local TV programs, and visit children confined to hospitals. Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day was released on December 20, 1968, on the same bill as The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit starring Dean Jones and Kurt Russell. Advertised as “All-Nooh,” alerting audiences that this was not a re-release but a fresh visit with the lovable residents of Pooh Corner, Pooh’s latest big-screen adventure was a sweet sensation.

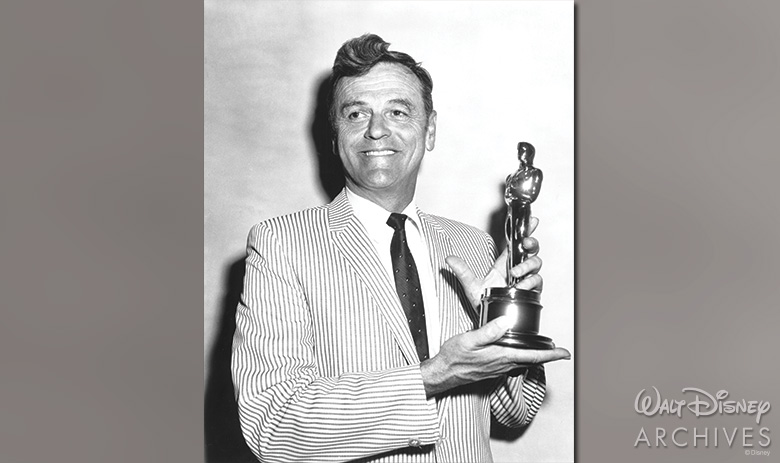

Winnie the Pooh Wins Big

Though production began after Walt’s passing in 1966, the story and songs had been created with Walt’s full engagement. According to Richard Sherman, who along with his brother was actively involved in the story sessions, “Every single note and every word was okayed by Walt.” On April 14, 1969, the new Pooh featurette was awarded an Oscar® as Best Cartoon Short Subject of 1968 at the Academy Awards® ceremony. Director Woolie Reitherman accepted the award on behalf of Walt Disney from presenters Tony Curtis and the Pink Panther, his voice cracking with emotion as he spoke of “another memorable moment we’ve all shared with Walt.” Winning an Oscar is quite the accomplishment for anyone, let alone a “silly old bear,” and Pooh and his plush pals were now firmly established in the Hollywood firmament—while at the same time winning Walt a final, posthumously earned Academy Award.