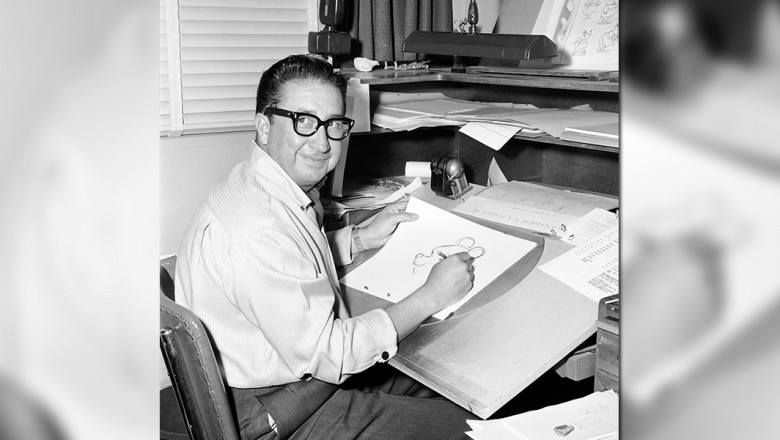

Now in the ninth decade of a life fully lived, Francis Xavier “X” Atencio still retains a gimlet sparkle in his eyes, and the mischievous spirit that no doubt helped lead him to creative triumphs throughout his career still animates his spry frame. His comic timing is impeccable, as we pleasantly discover during a visit to his comfortable home on a scenic hilltop overlooking Woodland Hills, California, and he tells stories with an élan that many men half his age couldn’t muster. In a spacious wood-paneled room adorned by—not overwhelmed with—Disney mementos, he matter-of-factly talks about his glory days, first at the Disney Studios as an animator, later working with animator Bill Justice on the stop-action masterpieces Jack and Old Mac, Symposium on Popular Songs, and the opening sequence for The Parent Trap, among others. And then on to WED, serving as a creative mastermind on such attractions as Pirates of the Caribbean and Haunted Mansion. He paints a vivid portrait of an era that has faded into the mystic chords of memory, a world of pencil and paper, audiotape and film, slide rules and thick-black glasses… when if Walt said you could do it, well, you had to go figure out how. X Atencio’s days as a mesmerizing Disney storyteller may be in the past, but any man in possession of his towering gifts always has another tale to tell.

D23: How does a kid from Colorado join the Studio at age 18?

“X” Atencio: After I graduated high school in Colorado, I came out to California to go to school at the Chouinard Art Institute. At the end of a semester, a couple instructors told some of us to get our portfolios together and they would take them to the Studios to get critiques on our work. I had developed a character, Poncho, a Colorado Cowboy, and I had done a storyboard, but that was about it. And I thought, “I’ll never get a job over there.” So I went to Disney to see if I could get a summer job to make some money to go back to Art School. When I got there, George Drake, the fellow who recruited all us people, said, “Sit down here for a minute, I’ll be right with you.” And with that, three other guys from my classes came in and I thought, “There goes my job. I’ll never get a job now.” And George says, “We went through your portfolios and we like what you’ve done.” Would you be interested in coming to work for us?”

Quite a pinch-me moment?

Well I was living in Hollywood at the time, and from Hyperion to Western Avenue in Hollywood, if you happen to know the area, is a pretty good jaunt. And I ran all the way home. “I got a job at Disney!” I was so excited that I was going to work for Mickey Mouse.

Pinocchio was your first film for Disney. What was the very first character you worked on?

I went into production out of the Training Center with Woolie Reitherman. Bill Justice was his first assistant. I was his second assistant, an in-betweener, really. The first thing we were working on was Monstro the Whale. Then Jiminy Cricket, but mostly it was Monstro.

What do you remember about working at the Hyperion Studio?

At that point in my career, I was just an in-betweener. The Animation Department wasn’t privy to all the wonderful things that were going on in the studio. It wasn’t until you moved up to an animator that you were in meetings with Walt. But they kept us little in-betweeners off in the corner there to do our pick-and-shovel stuff. Almost as bad as the Ink & Paint Department!

Do you remember the first time you met Walt?

No, but I remember the first time Walt met me! I was waiting in the hall for the elevator, and Walt came by and waited for the elevator, too. So I said, “Hi Walt,” and he said, “Hi X, how are you doing?” I thought, “He knows me, he knows who I am!” I almost fell on the floor to kiss his boots. That was a wonderful feeling that this great man actually knew who I was.

What was it like to leave the Studio and head off to World War II?

When the [Animators’] strike came in 1941, I went out on strike. I didn’t know what I was out there for. But all my buddies were out there. When the strike was over [five weeks later], they called me and asked me to come back to work on Monday. I think they realized that I wasn’t a rabble-rouser. I said I’d love to but I just got a greeting from Uncle Sam, so I went right off to war. I was in England for two years, in Greenland for a year. Everywhere I went they knew I was a Disney cartoonist, I was like a real celebrity!

Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953), the first animated cartoon to appear in widescreen CinemaScope, won an Academy Award® for Best Short Subject (Cartoons). What do you recall about the making of that film?

That was my first screen credit. Ward Kimball recruited me to do that picture. He said, “You might want to work on our picture, we got one called Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, and it’s your style of animation and design.” We used to call them pointy nose characters as opposed to the little fat bunnies. Ward knew that I had a talent for this type of animation and design. I once asked Walt, “Why don’t we do something like UPA [United Productions of America] has been doing? I like those stylized characters.” He said, “They’re making pictures for the intellect, we’re making pictures for the heart. And there’s a hell of a lot more heart than there are intellects.”

What was the biggest compliment you ever received from Walt?

One time we were in Detroit at Ford making a presentation for Epcot. I made my presentation, and after that, we all got back on the plane and went on to New York to see the World’s Fair. And Walt came to the back part of the plane—this was the Gulfstream we used to fly in those days—and he went to the back of the cabin and took a little nap. And a bit later, he came out and drew the curtains open and said to [then vice president of advertising and sales] Card Walker: “Open up the bar.” So we all went up to the bar and Walt stood behind me and put his hand on my shoulder, and said, “You know, you did a good job, X. But don’t let it go to your head!” That was the way Walt was. He would compliment you with one hand and with the other hand he’d challenge you to keep it to yourself. I always remember that little scene of Walt being so personal with me.

What do you remember about your stop-motion days?

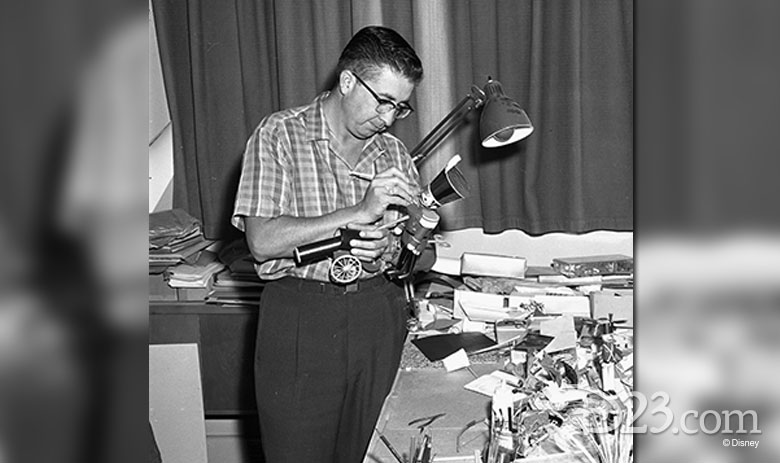

In the 50s, Bill [Justice] and I were working on short things like Jack and Old Mac [1956] and things like that, which were based on Walt’s doodles. Walt was a great doodler. At all the meetings I remember the secretary would pick them up and save them. So Walt suggested we do a film on doodles. It was crude and very short, but it was well received. And then we moved on to the stop-motion Symposium on Popular Songs, which has much more detail. Bill was really good at animating these things, he had a lot of patience. I had none. I was more at the design end, designing the characters [rather] than the actual animation of the rags and bones and pieces of junk.

What do you remember about Babes in Toyland (1961)?

Well, if you’re watching, “my” soldiers were the ones with the straps on the back in the form of an X!

The stop-motion opening title sequence for The Parent Trap (1961) is the stuff of legend. What do you remember when you see that sequence today?

How much fun it was. I remember working on it with Bill [Justice] and T. (Thornton) Hee. T. was more of a designer and animator, more like I was. We were more alike. T. was an ego. That’s why didn’t stay at the studio for 900 years like I did. These guys kind of felt like they were as talented as Walt was. And they were, maybe, just in a different way. T. was a great talent, but he wasn’t a Walt Disney.

Your career can be divided into three parts: First you were an animator, then a designer/stop motion animator, then you have this fantastic career at WED [Walter Elias Disney Enterprises, now Walt Disney Imagineering]. Looking back, which role did you most enjoy?

People often ask me which phase I enjoyed the most, and I’d have to say it was my time at WED. Primarily because that was an assignment I received directly from Walt. I remember when he called me up to his office and he said, “Well, X, I’ve been wanting to get you to WED for some time, and now is a good time to go.” I said, “Okay, boss, whatever you say.”

What were your early days at WED like?

Nobody knew what I was supposed to be doing. I just kind of flubbed around and then latched on to [Disney Legend] Claude Coats, who was one of my favorite guys, and helped him do the design for Primeval World. I worked with Claude for about a month or six weeks, then Walt called me and said he wanted me to make the script for Pirates of the Caribbean. I had done storyboards before, but never a script. So I put on my pirate hat and dug out any information I could find out about pirates. The first thing I worked on was the Auctioneer scene, and I sent it over to Walt and he said, “Fine, keep going.”

What was it like at WED and you heard Walt was coming over? Were you nervous?

You would be. First, you’d hear that chronic cough. “Here he comes,” we’d think. He never came with an entourage. He wanted to be alone to think with us. I remember you’d be at the storyboard, and you’d have your back to him. And he’d be in his wooden chair. And then you’d hear him tapping his fingers on the arm of the chair, and he was suddenly way ahead of you. And he’d talk about a board further down in the sequence than where you were, and he’d say, “Why don’t we take that sequence down there and move it up here? We should have thought of that.” If he were with you, boy, he’d be standing up there dancing, doing the whole thing. If he wasn’t, he’d be coughing with disappointment.

What did Walt say when you first showed him Pirates in mock-up?

We mocked it up on a soundstage in full size and we pushed Walt through it, we rigged up a cart that moved about the same pace the boat would and we moved him through and we had the Auctioneer up here and he said, “What do ye offer this buxom wench?” and on the other side a pirate yells, “Six bottles of rum, etcetera, etcetera.” But it was hard to hear, and I said, “I’m sorry Walt you can’t hear stuff too clearly.” And he said, “If you go to a cocktail party you tune in on one conversation, and then you tune in on that one. Every time they come through they’ll see something new.” And I thought, “Why the heck didn’t I think of that?”

Was Walt concerned at all about whether or not Pirates was appropriate for a Disney audience?

Yes there was some talk about it. They put up a sign hanging there behind the Auctioneer that said, “Take a Wife.” They were not just doing hanky-panky, they were shopping for a wife or a mate. That took the onus off it being too vulgar.

You wrote “Yo Ho (A Pirate’s Life for Me). Where did that come from?

The last meeting we had, I suggested to Walt maybe we should have a song in this one. I had a lyric in mind and kind of a melody so I half sang it and half recited it. He liked it, he said, “It’s good. Get George [Bruns] to do the music for it.” So George and I worked on the music. Later I did the Haunted Mansion “Grim Grinning Ghosts (The Screaming Song)” and suddenly I became a songwriter.

“Walt was a great doodler. At all the meetings I remember the secretary would pick them up and save them.” —X Atencio

There’s a school of thought about Haunted Mansion, that [artist and Disney Legend] Ken Anderson came up with the scary side and [animator/designer and Disney Legend] Marc Davis the humorous. Is that true?

I don’t think so. Walt implanted this in Marc’s mind. This was basically Walt’s idea. We researched Japanese spooky stuff, and Walt didn’t want any blood and guts. In the song “Grim Grinning Ghosts,” I say, “Come out to socialize.” That was the key to it. They terrorize but their main point was to socialize. Walt bought that idea. That was the hook, the Disney angle. “Socialize” is the key word.

What was the biggest challenge facing the team creating Haunted Mansion?

[Imagineer and Disney Legend] Yale Gracey worked on it and came up with some great illusions, and we ran into the problem of how were we going to move people through [efficiently]. And Dick Nunis kept saying we had to get capacity. Hopalong Capacity we used to call him [Nunis].

What was it like working with Paul Frees, the voice of Haunted Mansion’s Ghost Host?

Paul Frees would come in on a call and spend the first half hour telling you how great he was. And you would say, “Okay, Paul, can we get to work now?” And he’d take a script and just run with it. Man, he was a genius. One take! Other people would try doing it all sorts of ways. Not Paul. He just ran with it and he’d put things in it and ad-lib it at exactly the right place. I couldn’t think of it, but it was always a great addition.

Which do you like more, Pirates of the Caribbean or Haunted Mansion?

Oh, the pirates. But I love the ghosts, too.

In 1997, the Auctioneer sequence in the Pirates attraction was changed so that the pirates pursued women holding pies. Later they also added Jack Sparrow. Do you like the changes?

I liked adding Jack. The pirates chasing the gals… nobody asked me but my reaction was this is Pirates of the Caribbean not Boy Scouts of the Caribbean!

Do you ever wish you were working now with all the new technology?

Yes and no. I enjoy my retirement. I paid my dues. I remember when I retired, John Hench told me, “You’re going to get tired of playing golf. Then what are you going to do?” And I said, “I’m going to clean out the garage for one thing.” I still haven’t cleared out the garage!