By the D23 Team

Since 2015, historian Didier Ghez has been shining a light on the art and animators of The Walt Disney Studios in his book series, They Drew as They Pleased. This ambitious project documenting the history of Disney animation uncovered a trove of previously unpublished artwork, history, and anecdotes that give an unprecedented view into how the films, characters, storylines, and unique Disney look-and-feel came to be.

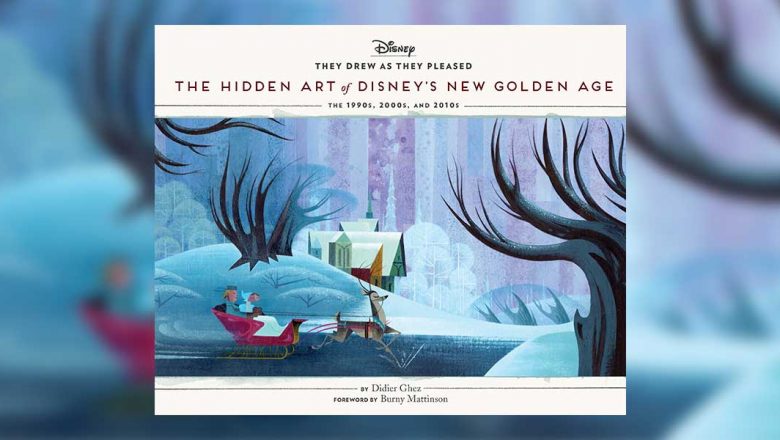

This final entry in Ghez’ series, They Drew as They Pleased: Volume 6—The Hidden Art of Disney’s New Golden Age, focuses on the 1990s through 2010, when Walt Disney Animation Studios experienced a dramatic creative shift as advancements in digital technology gave rise to computer-generated animation and produced blockbuster hits such as The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King, Tangled, Wreck-It Ralph, and Frozen. To learn more about this book, which is available for preorder now, read our exclusive Q&A with Ghez below:

D23: The Official Disney Fan Club: Can you tell us about the genesis of the They Drew as They Pleased book series?

Didier Ghez (DG): They Drew as They Pleased is a series of six art books spanning the full history of Disney animated features, focusing on the art of Disney “concept” artists.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, most artists around the world were unemployed. One of the only places that was hiring artists at the time was the Walt Disney Studios. The best among the best of those artists (men and women) were tasked by Walt to “draw as they pleased” to inspire their colleagues, to stimulate their imagination, and to take them in unexpected visual directions. They became the first “concept” artists.

This art book series explores, in detail and decade-by-decade, the art and life of the most prolific and creative of Disney’s concept artists, relying on newly rediscovered pieces of artwork and never-seen-before documents.

Each of the six volumes contains more than 400 never-published-before pieces of artwork and focuses on the careers of artists as diverse as Albert Hurter, Ferdinand Horvath, Bianca Majolie, Sylvia Holland, or, more recently, Mike Gabriel and Michael Giaimo, thanks to previously untapped interviews, diaries, and correspondence.

D23: What were some of the most exceptional discoveries you made while working on this series?

DG: Some have nicknamed me “the Indiana Jones of Disney historians,” which always makes me smile. While working on the first volume of the series, I had the pleasure of discovering the diaries and correspondence of one of the most important Disney artists of the 1930s, the Hungarian Ferdinand Horvath. His diaries and correspondence had been lost for more than 20 years and through detective work, and thanks to the help of a good friend, I was finally able to locate them. They contained even more information than I could hope for, but the diaries were in German and the correspondence in Hungarian. Some good-hearted polyglot volunteers were kind enough to translate those documents for me, which allowed me to write a chapter about Horvath that gives you the impression of being at the Studio with him in the 1930s.

Another astounding and totally unexpected discovery was a whole envelope full of very early Sleeping Beauty character designs by artist Tom Oreb, which had been languishing in a drawer for half a century and that are now featured in the fourth volume in the series.

As to the last volume of the series, which is being released this year (The Hidden Art of Disney’s New Golden Age), the most exciting find must have been all the early character designs for Who Framed Roger Rabbit developed in the early 1980s by artist Mike Gabriel, which you will discover in a book for the very first time.

D23: What are some of the highlights of this sixth volume in the series?

DG: As in previous volumes, 90 percent of the illustrations have never been seen before. The text is based on brand new interviews with three of the artists featured in the book (Hans Bacher, Mike Gabriel, and Michael Giaimo) and on privileged access to the Joe Grant collection thanks to the trust of his surviving daughter.

The first chapter in the book focuses on this outstanding Disney Legend, whose Disney career began in the 1930s and came to an end in the 1990s. At the start of his career, Grant worked with Disney artist Albert Hurter, who is the subject of the first chapter in the first volume of They Drew as They Pleased, taking our story full circle. The chapter about Joe Grant features countless treasures including rare documents about Joe’s work on Disney’s World War II projects, and outstanding pieces of artwork from both his careers in the 1930s (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Lady and the Tramp, Dumbo, etc.) and 1990s (Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King).

As mentioned, for the first time artwork from the initial, shelved version of Who Framed Roger Rabbit is revealed in this volume. The book also contains hundreds of pieces of never-seen artwork from some of Disney’s most beloved classics of the New Golden Age (Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, Frozen, etc.), as well as concept art created for shelved animated features never-before-discussed in book form: Sweating Bullets, Fraidy Cat, Gigantic, etc.

Once again, it is a feast for the eyes that should satisfy both casual enthusiasts and Disney history specialists.

D23: What do you consider as some of the highlights of the series?

DG: I mentioned a few of them in my previous answers, but let me add a few others:

In the first, second, and fourth volumes of the series, I have included in-depth chapters about very important female Disney artists: Bianca Majolie, Retta Scott, Sylvia Holland, and Mary Blair. The life and career of Mary Blair was already well-known, but the life and career of her colleagues Bianca Majolie, Retta Scott, and Sylvia Holland not so much.

Speaking of Mary Blair, in the chapter about her (in the fourth volume of the series), I was proud to feature only artwork that had not been featured in any books before.

In the fifth volume of the series, I was able to pay homage to two of my favorite concept artists: Ken Anderson and Mel Shaw. I had the chance to get to know Mel Shaw personally toward the end of his life and to visit his workshop. As to Ken Anderson, I had always been fascinated by his character designs, especially those he created for Robin Hood (released in 1973, the year of my birth) and that explains why, when I opened the boxes of Robin Hood artwork that are preserved at the Disney Animation Research Library, emotion overcame me and I started crying.

Finally, in the sixth volume of the series, one of the highlights was the fact that I had the opportunity to select artwork to illustrate the chapter about Mike Gabriel in the presence of Mike Gabriel himself. He was generous enough to confide in my taste, but I was privileged to get his guidance while making my selections.

This whole series is a labor of love and the journey to complete it was the ride of a lifetime.