By Dave Smith

In helping to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Walt Disney Archives, the Archives staff wanted to dig deep into their vaults to share an enlightening historical article with Disney fans. The following is an essay that Disney Legend, and Walt Disney Archives founder, Dave Smith wrote for a screening series hosted by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 2005. It is presented here in honor of Earth Week, and the legacy of nature filmmaking pioneered by Walt Disney more than 70 years ago.

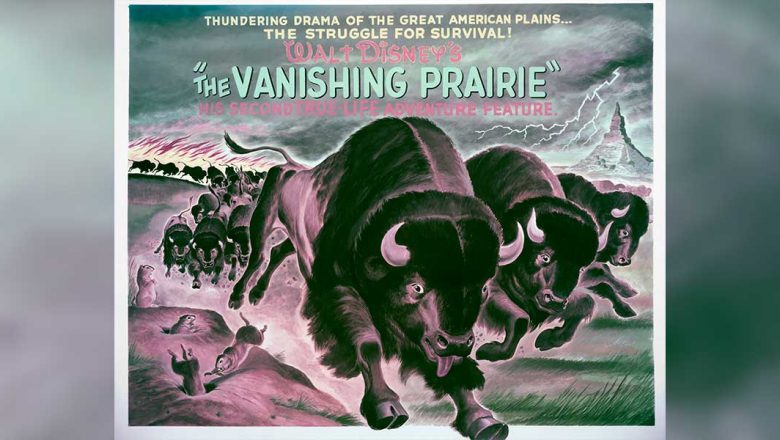

Probably one of the best known and most highly regarded of Walt Disney’s series of True-Life Adventures was The Vanishing Prairie. It was the second feature-length film in the series, coming a mere nine months after the release of The Living Desert, and thus being only the second feature released by Disney’s fledgling Buena Vista Distribution Company. Disney had established Buena Vista when RKO, who had been handling the distribution of Disney films, balked at releasing a feature-length nature documentary. With the new distribution set-up in place, Walt Disney now had more control over the types of films that he wanted to make.

Work on what would become The Vanishing Prairie actually began in early 1951, with the opening of story number 1815 at the Disney Studio. The film was tentatively titled Bighorn Sheep, and was to be filmed by Herb Crisler and directed by Jim Algar. At the time, it was merely thought of as one of the two-reel featurettes for the series. Over the next year, several more story numbers were established—1820 (Prairie Story), 1821 (Cat Family), and 1829 (Field Trip—Armadillo). Even before the success of The Living Desert in 1953, Walt Disney realized that feature length was the way to go with the True-Lifes. Theaters, naturally, paid higher rentals for a feature than they did for a featurette. So, in May 1953 he decided to combine these various stories into a feature with the working title of The Prairie Story. The title became The Vanishing Prairie by September.

The writers, Jim Algar, Winston Hibler, and Ted Sears, decided to cover the wildlife in the vast area from the Mississippi to the Rockies, and from the Gulf of Mexico to the plains of Canada, following through the seasons of the year from spring to winter. The film relates the story of the American prairie, whose birds and animals were brought to the verge of extinction, and yet managed to continue their fight for survival. It is the story of the pronghorn antelope, the migratory birds, the prairie dog, the bighorn sheep, the mountain lion, the buffalo, the prairie chicken, the sage grouse, and other creatures who once made the prairie their home. Walt Disney wrote, “The incredibly vast herds and flocks swept aside in that incredible passion for a piece of virgin American soil have dwindled to small groups. Yet remnant herds, as wild as ever their kindred were, still roam the open range, protected by sanctuaries and preserves.”

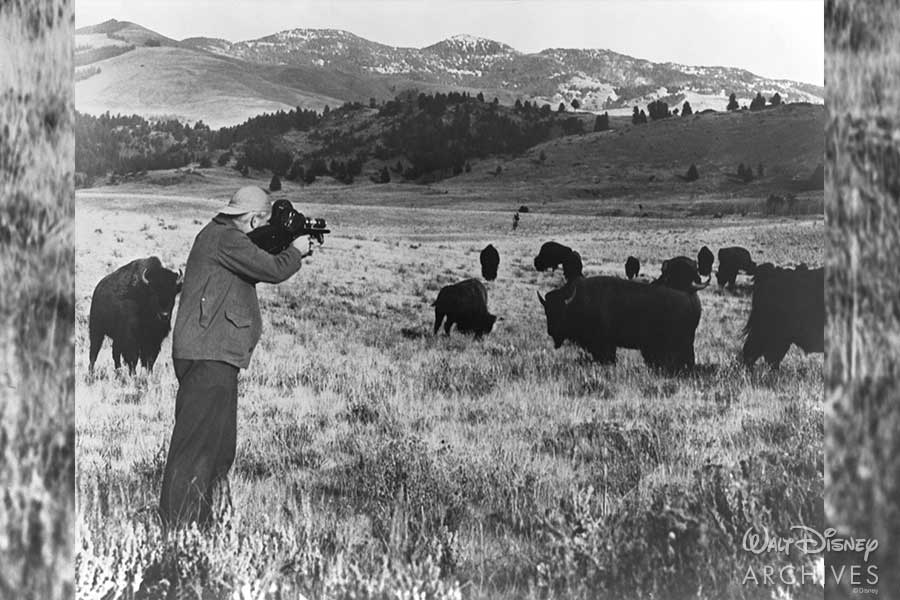

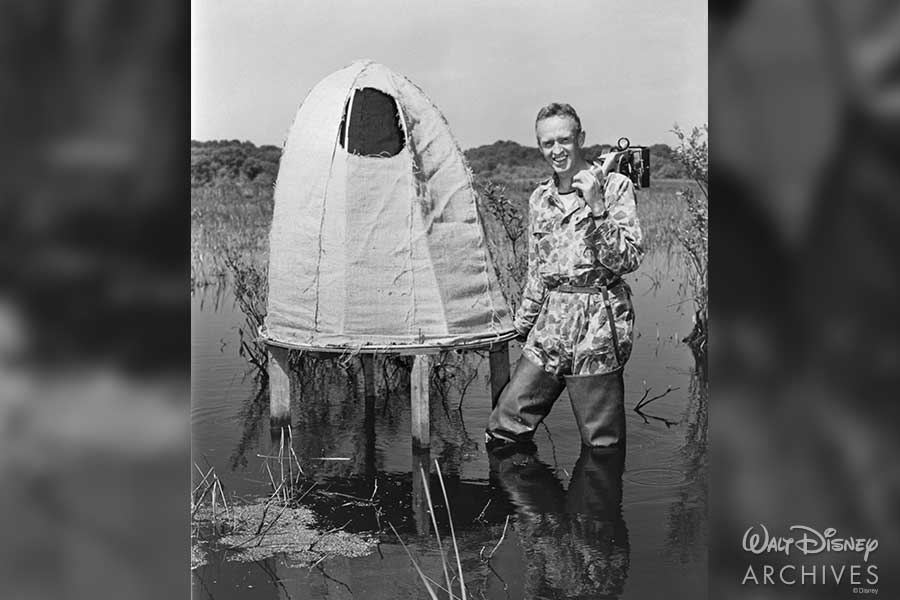

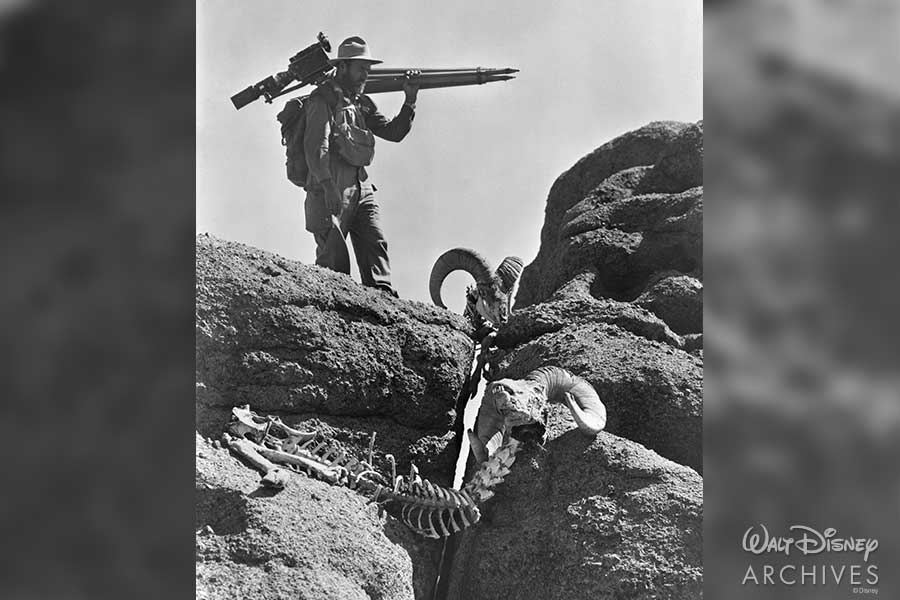

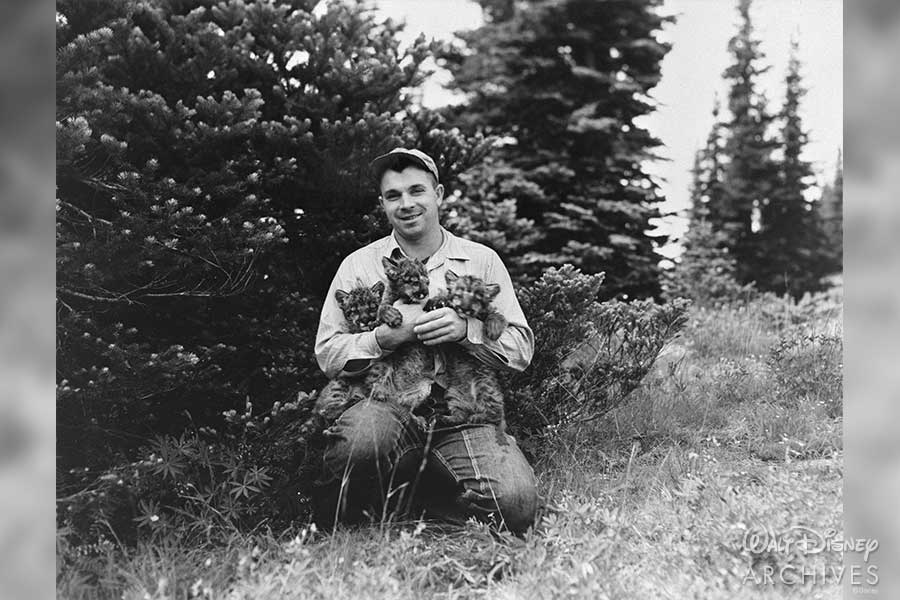

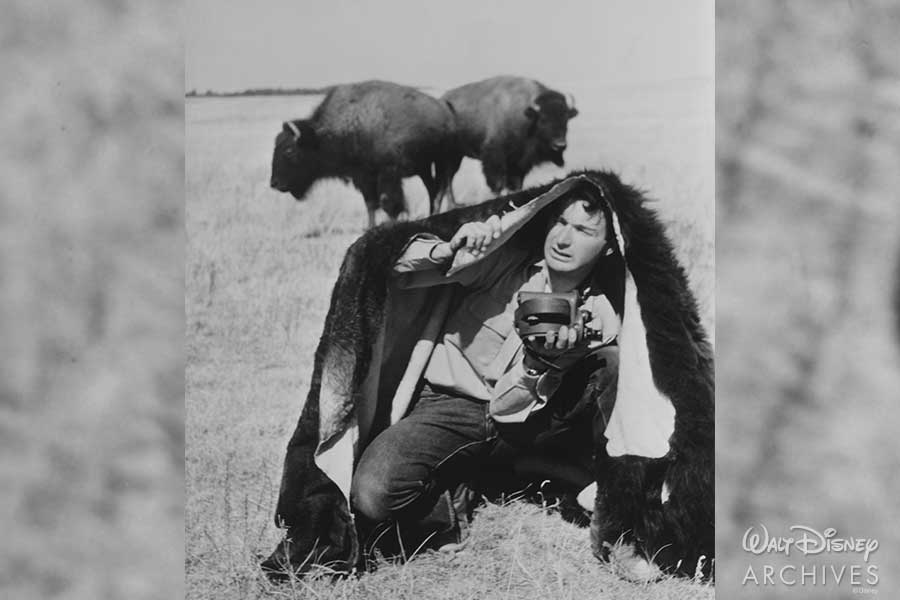

A dozen different nature photographers would eventually be credited with the striking footage that was compiled into the film. Notably, Tom McHugh, Jim Simon, and Warren Garst were sent to Crow Indian land in Montana to photograph the largest remaining herd of buffalo (over 1,500 head). Murl Deusing captured migratory wildlife mistaking ice for open water. N. Paul Kenworthy Jr. created a cutaway of a prairie dog home. Dick Borden specialized in high-speed photography and caught slow-motion studies of Canadian geese alighting on water. Herb Crisler and Cleveland Grant climbed high into the Rockies to find the bighorn sheep. And, in one of the most dramatic shots, Lloyd Beebe and Jim Simon were able to film a scene where a cougar makes a complete circle around a hiding fawn without seeing it. Other photographers were Stuart V. Jewell, Bert Harwell, and Olin Sewall Pettingill Jr. As with other films in the series, the footage was shot in 16mm Kodachrome, and then blown up to 35mm by special effects wizard Ub Iwerks. Iwerks also doubled in smoke, rain, and sky where needed.

According to photographer McHugh, Walt Disney wanted drama, emotion, humor, and struggles in his film. In order to capture striking buffalo footage, McHugh donned a buffalo robe and was thus able, with a hand-held camera, to sneak up on the grazing buffalo, “which seemed to regard him as some odd-shaped member of their own race and tolerated him accordingly.” 16-power telephoto lenses were often used to get intimate close-ups. Since it was not possible to have the animals do what the photographers wanted them to do, one would often find a photographer taking days to get just one usable shot. Film was cheap; eventually 70 times more film was shot than could be used.

Erwin Verity acted as production manager, and the film was put together by director Jim Algar, associate producer Ben Sharpsteen, and editor Lloyd Richardson, with overall supervision by Walt Disney. The film’s budget was only $382,600. As the film was progressing, non-critical reaction screenings were held in November 1953 and May 1954, with high praise from all who saw the footage. A 43-piece orchestra recorded the score by Paul J. Smith in five sessions between March 21 and May 13, 1954, on Stage A at the Disney Studio. Technicolor released the color negative to Disney in April 1954, negative cutting was completed in July, and the film was released on August 16, 1954 (along with a reissue of Willie, the Operatic Whale, that had first appeared in Make Mine Music eight years previously). The Vanishing Prairie was reissued in 1964 and 1971, and released on video in 1985 and 1995.

Some critics condemned Disney for using some staged shots, though the photographers were quick to defend their actions. In Chicago, the censors ordered deletion of a shot (by Jim Simon and Tom McHugh) showing a buffalo calf from the moment of birth. But other than that, the film was glowingly received by critics. As Walt Disney summed it up, “Our naturalist cameramen found and assembled an eloquent reminder of a past day in human and natural history in the animal personalities of a not-yet-completely vanished prairie.”

The Vanishing Prairie is now streaming on Disney+