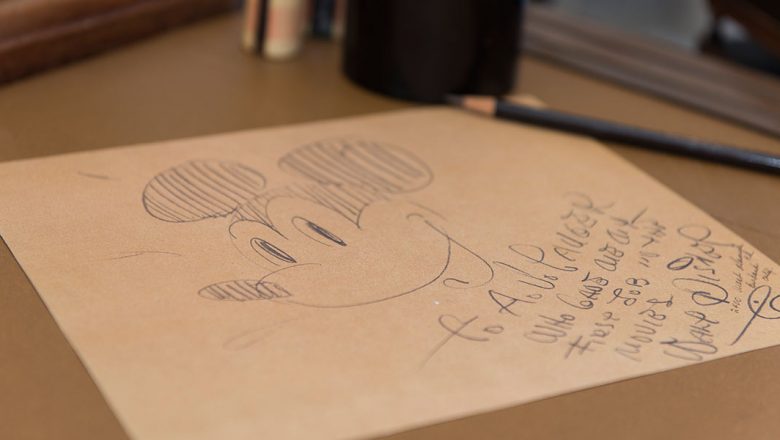

Walt Disney’s hand-drawn greeting to his first mentor is reproduced as one of the 23 treasures “From The Office of Walt Disney” for the 2016 D23 Gold Member Gift.

By Stacia Martin

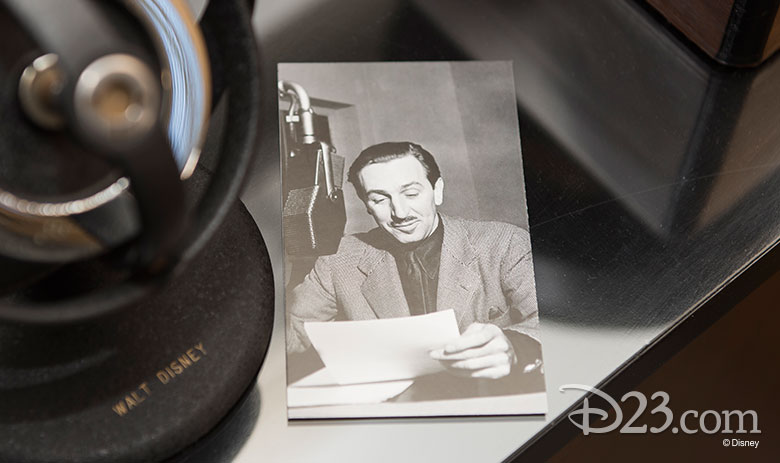

Walt Disney was proud to hail from America’s heartland. Even as achievement and fame made him a citizen of the world, he never lost sight of his roots and stayed in touch with many friends from his Missouri days—including his second grade schoolteacher. Walt took particular pleasure in acknowledging those who had helped steer him towards success, and in the case of Mr. A. V. Cauger of Kansas City, he was not alone.

Arthur Vern Cauger opened the Kansas City Slide Company in 1910 and grew his business into the Kansas City Film Ad Company, creating advertising graphics and simple stop-motion animation for cinemas. Among the young artists who broke into the picture business under Cauger were Isadore “Friz” Freleng, J.B. “Bugs” Hardaway, Ub Iwerks… and 18-year-old Walt Disney, hired in 1920. Working for Mr. Cauger inspired Walt to move beyond commercial illustration and explore the possibilities of film; he enrolled in night classes at the Kansas City Art Institute, and experimented in a makeshift studio behind the family home, using a camera loaned to him by his supportive employer.

Walt struck out on his own in May 1922, opening his short-lived but innovative Laugh-O-gram Films Inc. Despite its financial failure, Walt was determined to continue, and joined his brother Roy in California in July 1923. The Disneys’ new studio launched in October, and before a decade had passed, many of Walt’s fellow Kansas City Film Ad cohorts, including Freleng, Hardaway, and Iwerks, came west to animate for them. While Freleng and Hardaway would eventually depart (and find particular fame at Warner Bros.), Ub Iwerks became a Disney mainstay. When their star character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, vanished on a technicality, it was this future Disney Legend who conspired with Walt to design and breathe life into their hope for the future: a cartoon mouse named Mickey.

A. V. Cauger continued his Kansas City business for many years, justifiably proud of the talents he had nurtured. He was doubtlessly most proud of Walt Disney, and pleased that Walt had made it a point to both publicly acknowledge his debt to his old boss and maintain contact with the self-effacing animation pioneer. In December 1944, Mr. Cauger and his wife, Nina, themselves took a trip to California—an event that would not go unheralded.

Walt’s Burbank studio was not yet five years old when he welcomed his Missouri mentor and toured him through the custom-built, air-conditioned motion picture plant. Perhaps the unique, independent wings of the Animation Building, designed for optimal natural artists’ light, brought back memories of the enormous multi-paned window wall in Kansas City Film Ad’s central work room, where both Walt and Ub Iwerks had spent many long (and warm) hours at the drawing board.

Mr. Cauger’s big night arrived on December 28, when the celebrated filmmaking fraternity he’d founded reunited to salute him with a testimonial dinner. The event was held at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, site of the first Academy Awardsâ ceremony. In addition to Walt and Ub, Friz Freleng and “Bugs” Hardaway, a host of old friends attended, all grateful for the vision of one man who had encouraged the potential within so many creative novices.

To commemorate the evening, a keepsake book was assembled for the Caugers. Titled simply “Memories,” the oversized autograph album featured wooden covers and the relief-cut image of a cozy cabin and pine trees on the front. Inside, on textured brown paper, each of the animation community’s brightest paid tribute to the man who had launched their careers. Many wrote their sentiments, some, like Ub Iwerks, drew caricatures of themselves, still others drew famous characters with which they had become associated. Each used graphite pencil—the key implement of their chosen craft.

By 1944, Walt Disney no longer drew on a regular basis, though he liked to “keep his hand in” and retained a cartoonist’s touch in his strong, visually distinctive signature. In Kansas City, young Walt had drawn a lot, dreaming of new directions that those drawings might take. It was appropriate, then, that on this occasion Walt drew once again for Mr. Cauger. For this very personal tribute, Walt selected the character often identified as his “alter ego,” Mickey Mouse. Not only was Mickey Walt’s greatest success, but most importantly, Walt maintained a personal bond with his creation by performing his voice (exclusively until 1946, occasionally thereafter). Also, Mickey’s personality often mirrored that of a cheery, sometimes bashful Midwestern stripling, prone to expressions like “gosh,” “you bet” and “aw, shucks…” probably not unlike a teenaged Walt.

“To A. V. Cauger — Who gave me my first job in the movies — Walt Disney” reads the inscription beneath a mischievous, merry portrait of Mickey, drawn by Walt with simplicity and the unmistakable flair of pleasure.

Amazingly, just eight years after Walt began work at Kansas City Film Ad, his own animated character would impact not just his world, but the rest of the globe as well. Although in 2016 we celebrate the 88th anniversary of that all-important Steamboat Willie premiere, it is worth a moment reflect as well on the 72nd anniversary of Hollywood’s tribute to A. V. Cauger. Mickey Mouse’s success is rooted in that same celebratory spirit, proving that cherishing those who make dreams possible is just as important as creative endeavor itself.