By author and historian Michael Crawford

In 1976, Imagineers attempted to decide what the scale of their project could be, given the resources available. The nation again found itself in the midst of an energy crisis and economic malaise, and despite extensive recruitment efforts, it began to appear that not enough corporations and foreign governments could be recruited to make both World Showcase and the Future World Theme Center economically viable.

Proposals to scale down the concept continued throughout the year. In late 1976, with executive review pending, legendary Imagineers Marty Sklar and John Hench famously pushed the models together and EPCOT Center was born. The new park would now have two main areas: Future World and World Showcase. One would be a showcase for the latest innovations of American industry; the other would be a permanent international exhibition. But while this EPCOT Center sounds familiar, it had major differences from the park we know today.

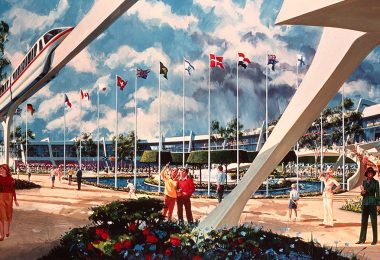

Guests would enter this EPCOT Center through World Showcase, which would serve as the park’s Main Street. Resembling the World Showcase proposal announced a year earlier, the wishbone-shaped complex of modernist buildings surrounded a central plaza housing performance areas and gardens as well as waterways and a Tower of the Four Winds sculpture. A variety of attractions planned for the international pavilions included a Rhine River cruise through Germany, a cable-car ride past Venezuelan waterfalls, and an Omnimover trip through sumptuous Japanese gardens and scenery.

Facing World Showcase across a large central lagoon and past a cluster of towering spires was Future World. Here, the EPCOT Theme Show would serve as the introductory presentation of EPCOT Center. Focusing on man and his spaceship earth, the show offered a moving experience combining a one-of-a-kind theater with film and automated techniques. Afterward, guests could learn about the future of a number of fields by visiting other Future World shows and exhibits. They could even take in a panoramic view of the park from a restaurant and cocktail lounge in one of the spires overhead.

While many of these ideas never came to fruition, some concepts—and menu items—made their way into the park on opening day. For Canada, planners even projected a menu for the Canada “buffeteria” that included cheddar cheese soup, a modern-day favorite. Plans for the Germany pavilion included a Munich beer hall atmosphere similar to today’s Biergarten, and although the World Bazaar never made it into the park, the name was re-used for Tokyo Disneyland’s entrance area in 1983!

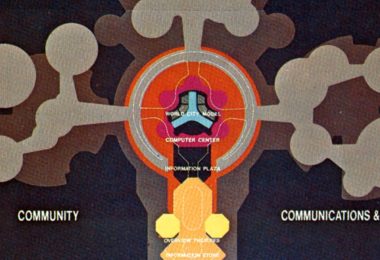

Future World’s pavilions were grouped into two major areas on the east and west sides of the park. They were connected to the CommuniCore by two “malls” and featured pavilions devoted to related fields of study. The East Mall connected to the bio-science-related pavilions of Oceanography, Health, and Food/Agriculture; the West Mall led to technology-based pavilions including Energy, Transportation, and Space.

A major shift in EPCOT planning occurred between April and May 1977, when Imagineers decided to “flip” the positions of Future World and World Showcase. This marked the advent of what the company announced as Master Plan 5. Heralded as a “conceptual breakthrough,” it presented a park similar to the one we know today. Imagineers now had a clear vision for most of the Future World pavilions. For the first time we see attractions based on The Land, The Seas, and the rest that feel familiar.

Spaceship Earth, an evolution of the earlier EPCOT Theme Show, was now the dominant visual icon of the park, its enormous golden dome facing the entrance plaza. Providing the gateway between Future World and World Showcase was the U.S.A. pavilion—soon to be known as The American Adventure. Resembling something of a cross between a UFO and a modern art museum on stilts, the circular pavilion served as the introduction to World Showcase.

World Showcase now circled a lagoon instead of a plaza, although it still resembled the sleek semi-circle design of previous schemes. This would change in 1978, when legendary Disney art director and Imagineer Harper Goff designed a World Showcase based on individual buildings heavily themed to the architecture of specific nations.

After much courting, Disney finally had a critical breakthrough on January 6, 1978, when General Motors signed an agreement to sponsor a Transportation pavilion in Future World. The G.M. deal signaled a vote of confidence in the Imagineers’ plans and gave Disney’s management leeway to proceed. Soon after, on January 27, Exxon signed a deal to sponsor the Energy pavilion.

In October 1978, Card Walker made a final announcement that the company intended to proceed with EPCOT Center. Speaking in front of Cinderella Castle to 2,500 delegates of the International Chamber of Commerce at their 26th World Congress, Walker declared that EPCOT Center would open October 1, 1982, and revealed that G.M., Exxon, Kraft, and AT&T had signed letters of intent or contracts to participate in Future World. Ten nations had expressed interest in World Showcase, including the United States, Mexico, Japan, West Germany, France, Canada, Israel, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, and Italy.

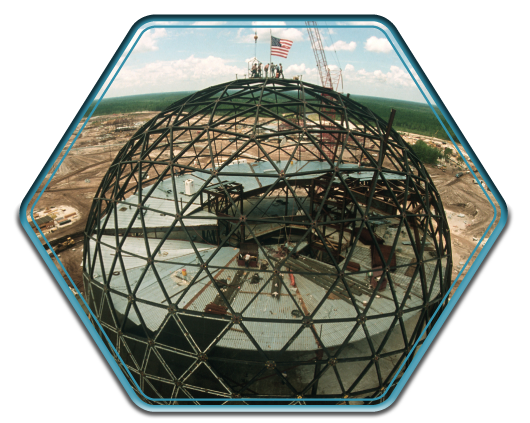

Finally, after years of planning, ground was broken for EPCOT Center on October 1, 1979. A golden outline of Spaceship Earth, standing 178 feet high, was suspended from construction cranes while a massive 40-ton General Motors Terex truck delivered the first ceremonial load of dirt for construction. Then Florida Governor Bob Graham was on hand for the festivities, as were former governors Haydon Burns, Claude Kirk, and Reubin Askew; these men represented a continuous line of state executives stretching back to Walt’s first Disney World press conference in 1965.

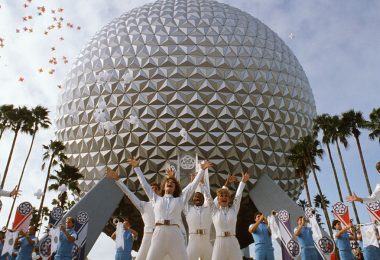

And so work began on what was, at the time, the world’s largest private construction project. Three years later, amid a wave of fanfare and a torrent of international media, Epcot Center (as it was named upon its debut) was officially unveiled on time, on October 1, 1982. A month of ceremonies followed, as each pavilion and attraction had its own special debut festivities. Other attractions and facilities would come online in the months and years that followed. While there were some bumps along the road early on—after all, the park’s many attractions were among the most complicated ever devised—the kinks were eventually worked out and record-setting crowds flocked to witness the 21st century made real.