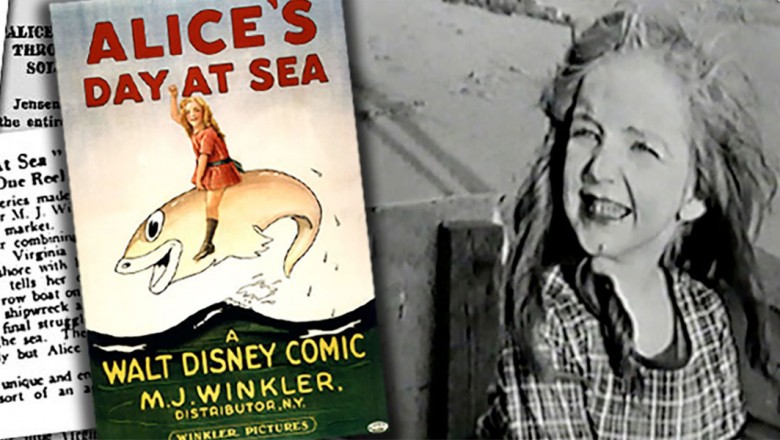

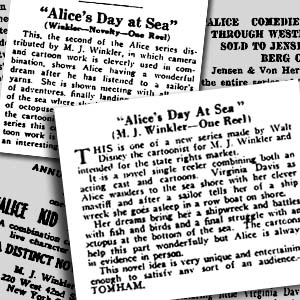

Walt Disney often said that he would “never lose sight of one thing… that it all started with a Mouse.” But while Disney’s biggest success surely began with Mickey, young Walt and a determined crew of animators were making cutting-edge cartoons several years earlier. March 1, 1924 saw the premiere of Alice’s Day at Sea — the second Alice Comedy, the first Disney film to be produced in California and the first to achieve nationwide distribution.

What were the Alice Comedies? In the late 1910s and early 1920s, it was quite the trend for theatrical short films to combine live action and animation. Series like Max Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” and John R. Bray’s “Colonel Heeza Liar” showed cartoon characters “living” in the real world. An artist’s hand would draw Colonel Heeza; then he’d jump off the page to bicker with his creators. In 1923, Walt Disney decided to reverse the idea: to put a real-life human into a cartoon world. At Disney’s Kansas City Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc. Studio, a pilot film called Alice’s Wonderland was made. Local child actress Virginia Davis played Alice, who visited the Laugh-O-Gram studio — then dreamed of traveling to “Cartoonland,” where cartoon crowds cheered her and cartoon lions chased her. The effect, involving cutting-edge superimposition, took a sizable crew of animators to get right: At the time, the Disney crew included Kansas City buddies Ub Iwerks, Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising.

Then Walt did something amazing: He produced the next Alice Comedy, Alice’s Day At Sea, single-handedly.

A little background: Disney’s Kansas City studio had been plagued by bad luck. A distributor called Pictorial Clubs hired Walt to produce seven Laugh-O-Grams fairy-tale cartoons, but Pictorial declared bankruptcy soon afterward, leaving Disney in the red. Alice’s Wonderland was intended as a showpiece to attract a new distribution deal. After making it, Disney moved to Hollywood, where he felt distribution would be easier to arrange and a studio easier to maintain. Ironically, Walt ended up striking a deal with a New York-based distributor — Margaret J. Winkler — and had to start work without much of a studio at all. Winkler wanted more Alice films fast; Virginia Davis’ family was glad to join Walt in California, but Disney’s artists couldn’t make the move in time to work on the first of the new shorts. Thus Alice’s Day At Sea was drawn and directed by Walt alone… and would reflect his vision precisely.

Alice’s Day At Sea opens with an alarm clock waking Alice’s live-action dog, Peggy, in her doghouse, after which the pooch escorts Alice to the beach in a kid-sized car. There Alice listens to an old captain’s fish stories — illustrated in blackboard-style animation, with a giant squid attacking the man’s boat. Alice wishes she were a sailor, too, and dreams her way to Cartoonland, where we see her ship foundering in a scary cartoon storm. When lightning sends the boat to the bottom, Alice wriggles out through the smokestack to explore the ocean floor. She thrills to a fish jazz band; then visits “King Nep[tune]’s Zoo,” where creatures like a sea lion, catfish and sea cows look just like you would expect in a cartoon.

But the fun is spoiled when a hungry shark arrives. Alice tries to flee in a nearby “sea-going hack” (a car!), but ends up getting gobbled. She slips out from inside the shark after he tries to swallow a swordfish, but more danger approaches: It’s the squid from the old captain’s story! He’s tangling Alice in his coils when Peggy and the captain awaken her, revealing that she’s actually just caught up in a fishnet — so everyone can share a relieved laugh.

For a film made by one animator, Alice’s Day at Sea brims with detail. The squid’s raw, animal menace is established when we see him eat an ill-fated salmon — though he’s still human enough to use silverware and salt the salmon before eating him! Walt continues a studio tradition by featuring the character of the swordfish, who had earlier appeared in the Laugh-O-Grams Four Musicians of Bremen and Jack the Giant Killer (both 1922). Day at Sea‘s live-action scenes sparkle with invention, too: Peggy’s doghouse is visibly larger inside than outside, with a comfy human-style bed for the hound to snooze on! (We’d be remiss not to mention that outside of the Alice Comedies, Peggy really belonged to Walt’s uncle Robert Disney.)

Distributed by Winkler on a states’-rights basis, Alice’s Day at Sea was a hit and launched an exciting series for Disney. As further Alice Comedies were completed, Walt’s Missouri animators joined him in Hollywood — and the Laugh-O-Grams’ cat cartoon star, later named Julius, joined Alice on-screen for more than 50 funny misadventures. But those stories can wait for another day.