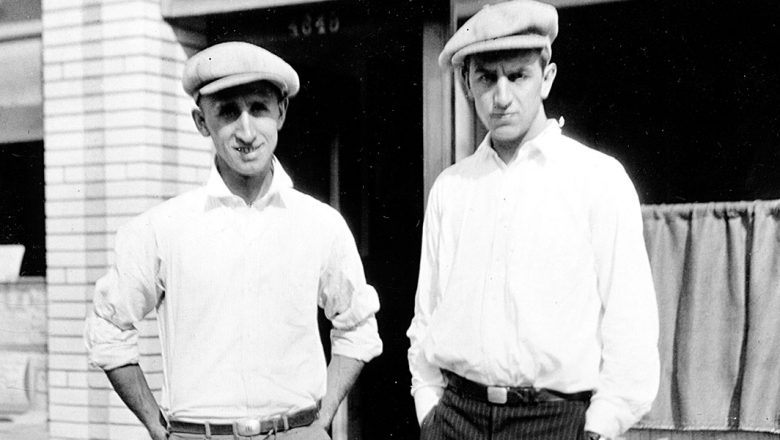

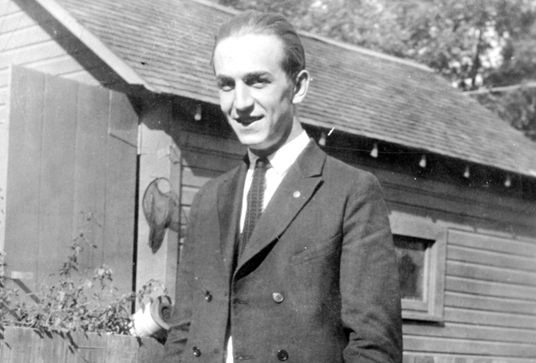

Walt (right), just months after arriving in California.

He’s with brother Roy in front of their first Hollywood Studio, on Kingswell Avenue.

1923.

In the glow of prosperity following World War I, America as never before sees itself as the land of opportunity, especially through the eyes of its youth. Many young fortune-seekers head for the Big City—Hollywood—glamorous home of the movies that are lighting up the silver screen, attracting one third of the nation to theaters at least once a week. Anything seems possible.

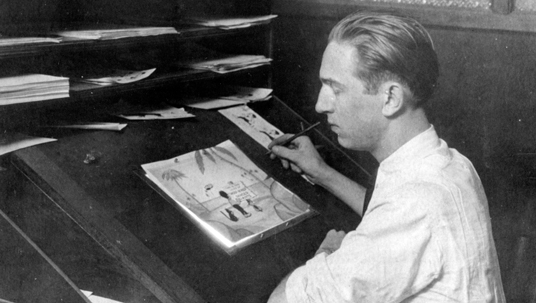

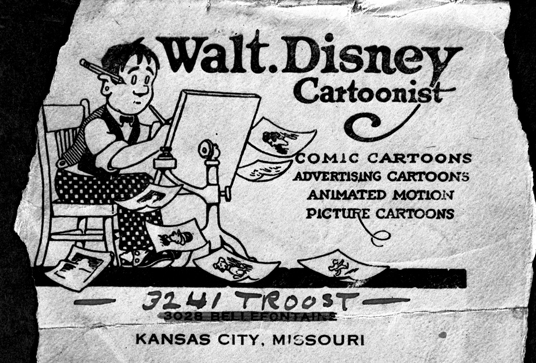

For a young cartoonist named Walt Disney, 1923 starts on a note of failure. His Kansas City animation studio, Laugh-O-gram Films, was foundering less than a year after its May 1922 incorporation. The Tennessee-based distribution company funding the six animated fairy tales Walt had created with a small group of young artists had gone belly up, and Laugh-O-gram was in danger of going bust itself.

Not that any of this deterred the young Walt. Like a Horatio Alger hero sprung to life, he brimmed with self-confidence and get-up-and-go, an innovative spirit that personified 1923’s youthful zeal. Walt’s older brother Roy, who was then convalescing from tuberculosis in a Los Angeles veterans hospital, later said his 21-year-old brother “had a persistency, an optimism about him, all the time. A drive.”

Daringly, in light of his studio’s free-fall, Walt spent the early months of 1923 attempting to create a new animated series. “I was desperately trying to get something that would take hold, catch on,” he said. The imaginative Disney hit upon a “reversal” of Max Fleischer’s popular Out of the Inkwell cartoons, which featured the animated Koko the Clown running amuck in the real world. With his usual flair for the technically innovative, Walt would produce a short incorporating a live action little girl in an all-cartoon world.

“We have just discovered something new and clever in animated cartoons!” Walt trumpeted in a letter to New York distributor Margaret J. Winkler about the Alice in Cartoonland concept. Though Miss Winkler expressed interest, only half the film was completed before money ran out entirely. Walt tried other projects, but it was no use: His employees abandoned ship, and with no money to live on, Walt slept in the Laugh-O-gram office, ate on credit at the small Forest Inn Café downstairs, and bathed once a week at Union Station for a dime. Finally a concerned Roy advised, “Kid, I think you should get out of there.”

That did it. Walt declared bankruptcy and joined Roy in sunny Los Angeles. He bought a train ticket: first class.

“Walt always had to have the best,”

noted his wife, Lillian, in telling the story years later. “I was in my pants and coat that didn’t match,” Walt later reminisced, “but I was riding first class.” The westbound young man departed Kansas City in July, and for Walt, a lifelong railroad enthusiast, the trip to Los Angeles was a thrill: “It was a big day, the day I got on that Santa Fe, California Limited.” And there was the gleaming promise of a shiny new start in Hollywood, already the fabled land of dreams-come-true.

Arriving in Los Angeles, the once-and-future cartoonist rented a room from his uncle Robert Disney, and, although he had included drawing materials among his few belongings, he said, “I was fed up with cartoons. My ambition at that time was to be a director.” The young hopeful hopped a bus for the movie studios and, following job interviews, hung out around the dream factories, keenly observing how scenes were staged and shot. Years later Walt recalled watching Western director William Beaudine in action. He would later direct “The Adventures of Spin and Marty” for TV’s Mickey Mouse Club in 1955.

But when Walt failed to land a movie studio job, he decided to tackle animation once again. In his Uncle Robert’s garage, Walt cobbled together an animation stand out of spare lumber and old boxes. On August 25, Walt wrote Margaret Winkler, saying he was in the process of “establishing a new cartoon studio” and suggesting she screen the unfinished Alice’s Wonderland. Disney’s initial faith in Alice suddenly paid off: Miss Winkler telegraphed Walt on October 15, offering a contract. Jubilant, Walt burst in upon his brother in the veterans hospital late that night to show Roy the telegram and urge him to jump aboard. Roy signed himself out of the hospital the following day, October 16, 1923, the same day Walt signed what Disney Chief Archivist Dave Smith describes as “the most important document in the history of The Walt Disney Company”: a contract for a series of Alice Comedies, the start of the Disney Studio.

With funding from Uncle Robert, Walt rented space in the back of a real estate office. By the time Walt celebrated his 22nd birthday on December 5, production was almost complete on Alice’s Day at Sea (he drew the animation entirely himself), and the finished short was delivered on December 26. By January 12, 1924, Roy had paid off the debts to Uncle Robert, and the Disney Bros. Studio moved to a next-door storefront by mid-February.

As 1923 became 1924, Walt Disney’s pioneering spirit was already clearly evident. Walt famously said, “it all began with a Mouse”—but it really all began with the ambition, imagination, and passionate dedication to quality of the youthful go-getter who journeyed not just to Hollywood but beyond… to the creation of a new, inspiring, and inclusive entertainment form called Disney.

And it all began in 1923.