By Jim Fanning

“To the youth of the world… in whose spirit and courage rests the hope of eventual freedom for all mankind… ” With these stirring words, Walt Disney opened his rousing live-action adventure film Johnny Tremain (1957). Colorfully recreating historic events of the American Revolution from the Boston Tea Party to Paul Revere’s midnight ride, Johnny Tremain is the story of a young silversmith apprentice swept up in the excitement of the battle for independence in colonial Boston. This engrossing tale centers on the unknown players of early American history, “the nameless ones, the unsung heroes,” as Walt called them. “The fierce desire for independence burning in the hearts of these unknown patriots made the deeds of our great men possible.” According to the great storyteller, Johnny Tremain is “about the nameless, unsung patriots whose hunger for freedom made possible the independence that is enjoyed in America today. For after all, the struggle for American independence is typical of the continuing fight for human liberty everywhere in the world.” To get your Independence Day celebration started off with a bang, here’s a sparkling star-spangled display of 13 — in honor of America’s original 13 colonies — fascinating stories all about Johnny Tremain.

The Story of Liberty: The Original Book

This extraordinary Disney film started with Johnny Tremain: A Novel for Old and Young by Massachusetts historian and novelist Esther Forbes. The author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Paul Revere and The World He Lived In, published in 1942, Ms. Forbes wrote Johnny Tremain based on her research for the Revere biography. Awarded the prestigious Newberry Medal for most distinguished contribution to children’s literature of 1943, the dynamic book has been in print ever since and is ranked 16th on the list of top-selling books for young people. Though Johnny is a fictional figure, the intriguing novel is historically accurate and full of the color and rich detail of that exciting era. For Walt Disney, history was indeed all about story, and he recognized a good historical story when he read one. Johnny Tremain is “a book about a boy who lived in the time of Paul Revere,” Walt noted, “and it tells a vital chapter of the liberty story. In fact, this book intrigued us so much that we… made a Technicolor® motion picture of it.” Reportedly Walt personally invited author Esther Forbes to the film’s opening in Boston, which she attended in style via limousine.

Tremain TV

Actually, Johnny Tremain started out as a small-screen production. Walt felt the beloved story was a natural for his Disneyland TV series. “We found ourselves facing an embarrassment of riches,” Walt said of the captivating material offered by Tremain. “Every page of research revealed fascinating material fairly shouting for picturization [sic]. If all the world is a stage, then all history is a great story storehouse and casting department rolled into one.” To dramatize the award-winning book for television, Walt turned to the talented scribe who wrote Disney’s sensationally popular “Davy Crockett” shows, screenwriter Tom Blackburn. The story was divided into two separate but interrelated episodes, the first set in 1773 and centering on the Boston Tea Party, the second taking place in 1775 and focusing on the Shot Heard ‘Round the World at Lexington. Finally, though Johnny Tremain was planned for TV, Walt made the decision to instead release the elaborately authentic film theatrically. As was often the case, the savvy showman spent far above the typically low TV budgets on his television productions. “We did shorten the schedule,” noted assistant director William Beaudine, Jr., “but it was very difficult to economize to the point of making it practical just for television release, because Walt Disney expected top quality.” To celebrate the film’s release in theatres, Walt hosted “The Liberty Story,” originally broadcast on May 29, 1957, previewing Johnny Tremain as well as screening Ben and Me (1953), a more fanciful look at the American Revolution. Eventually Walt proudly showcased Johnny Tremain on his TV show in 1958, in two episodes just as originally planned.

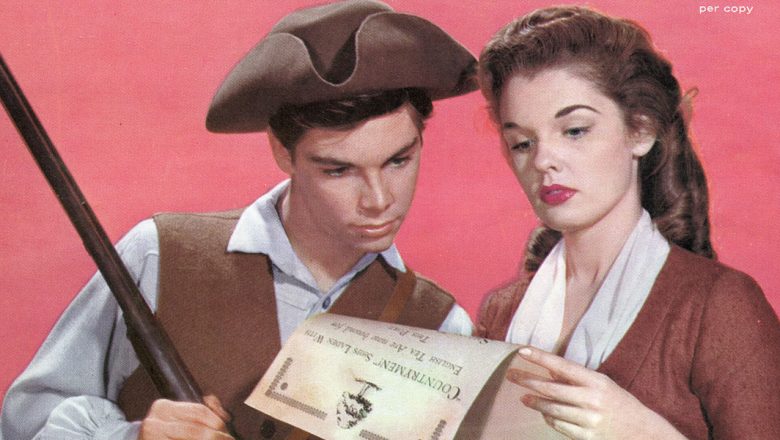

Johnny Tremain of Old Boston Town: Hal Stalmaster

Walt found the ideal actor to embody Johnny in 16-year-old Hal Stalmaster, brother of legendary casting director Lynn Stalmaster. “My brother didn’t help me one bit,” Hal was quick to note at the time of the film’s release. “He thought I was too young to start acting and besides, he didn’t think I could act!” Walt felt differently and awarded the talented teen the hefty role even though Hal’s only previous acting experience was as the young Olympic athlete Reverend Bob Richards on a TV show in which Hal’s prowess in track and field came in handy. Hal won the starring part as the teenaged patriot over a dozen other candidates. “People won’t believe me when I tell them this,” stated Stalmaster, not quite believing his good fortune himself, “but it’s true.” To prepare himself for the role, Hal had to re-orient himself from the atomic age to the War for Independence. “Johnny Tremain sounded like history at the outset. And it is, of course, in one sense. Unless you were there. Which I was. To really feel as Johnny felt, I found I had to get with his day and times,” explained Hal. “Then it was as uncomfortable as it was exciting, believe me, and I was happy each night to leave the embattled sound stage for the peace and quiet of 1957.” Hal made personal appearances (in full colonial regalia including his distinctive tri-corned hat), for example at the Roosevelt Theatre in Chicago, where he appeared with Annette, Doreen, Lonnie and other Mouseketeers. Hal also guest-starred with the Mouseketeers on TV’s The Mickey Mouse Club on May 1, 1957, to present a Johnny Tremain “Mousekapreview.”

Sons of Liberty

Johnny’s friend and fellow Son of Liberty Rab Sillsbee is played by Richard Beymer, who would later star as Tony in West Side Story (1961) opposite Natalie Wood. Sebastian Cabot portrayed cold-hearted tea merchant Jonathan Lyte (whose ostentatious motto is “Let There Be Lyte”) in his second Disney film (his first was Westward Ho the Wagons! in 1956). Trained in Britain’s Shakespearean theatre, Sebastian went on to be heard but not seen in his most beloved Disney roles: the narrator of the Winnie the Pooh featurettes and as the voice of Bagheera in The Jungle Book (1967).

Daughters of Liberty

Well-established in such diverse classic films as High Noon (1952) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Virginia Christine plays Mrs. Lapham, who turns her back on Johnny when he burns his hand in a silversmithing accident. (Virginia would later become most famous to audiences as Mrs. Olsen in a long-running series of TV commercials for Folgers Coffee.) Her onscreen daughter in this heroic tale, Cilla, is luminously portrayed by Luana Patten, former Disney child star who appeared opposite Bobby Driscoll in classics such as Song of the South (1946). In the mid-1950s Luana took on grown-up (or at least teenaged) roles in such films as Rock, Pretty Baby (1956), starring Sal Mineo, and of course Johnny Tremain, which marked Miss Patten’s return to the Disney lot. “During my first few days on Johnny Tremain,” said Luana, recalling the heartfelt welcome that greeted her return to the Disney Studio, “people kept coming up to me, shaking my hand and telling me about incidents that happened to me as a youngster. It really gave me a warm feeling to know that so many remembered me.” One of the most fascinating members of the cast (albeit in a small role) is Walt Disney’s younger daughter, Sharon, as Dorcas, friend to Johnny, Cilla and Rab — and who according to Luana, was a friend with Miss Patten when both girls were young children who made the Disney Studios their playground.

Leaders of Liberty

Johnny Tremain features a passel of real-life patriots, each portrayed by an experienced character actor, including Whit Bissell as Josiah Quincy, veteran character actor Rusty Lane as Samuel Adams and Walter Coy as Dr. Joseph Warren (who in the Tremain story surgically cures Johnny’s injured hand). A veteran of 500 movies, Walter Sande found his most unusual role as Paul Revere, to whom he bore a striking resemblance. Though the name of the horse from Revere’s famous nighttime ride is not known (as mentioned in the film, silversmith Revere borrowed the horse from Charlestown merchant John Larkin), Walter rode a chestnut mount named Sickle in Johnny Tremain, first having to master riding a small English-style saddle in two weeks of pre-production riding. For the filming of the first leg of the ride, the actor was startled by the speed with which Sickle galloped off. “I wasn’t sure if Sickle ever intended to stop,” Walter reported. “I was holding on for dear life.”

“Men seemed to gravitate toward these natural leaders by instinct,” observed Walt Disney of the heroes of the War for Independence. “But of them all, the figure of James Otis perhaps cast the largest shadow. He was one of the most brilliant men of his day and a great orator.” A large man, Otis is portrayed by larger-than-life Jeff York in a rare and moving dramatic performance. A favorite from his comedic appearances in Old Yeller (1957) and as legendary keel boater Mike Fink in the second set of “Davy Crockett” TV episodes, Jeff vividly delivers the film’s crucial speech about the importance of the cause of independence, and recognizes in young Johnny the hope for freedom’s enduring future.

The British Are Coming! The British Are Coming! Robert Stevenson

Johnny Tremain was director Robert Stevenson’s first Disney film but far from his last. “I was hired for six weeks, and I stayed for 20 years,” Robert was later to marvel. Walt was so impressed with the filmmaker’s fine work that Robert became Disney’s premier live-action director; he went on to helm such classics as Old Yeller and Mary Poppins (1964), for which he was nominated for a Best Director Oscar®. Aside from his directorial skills, Robert was perhaps the ideal choice to helm a story of English subjects discovering independence in America: “I was born in England,” he revealed during production of Johnny Tremain, “but I’ve been an American citizen for many years.”

The British Are Coming! The British Are Coming! (Part 2) Peter Ellenshaw

Like Robert Stevenson, legendary special effects artist Peter Ellenshaw was British-born but found a permanent U.S. home at the Disney Studio. Having relocated from England to add fantastical effects to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Peter shone in his first Disney assignment as production designer on Johnny Tremain. The brilliant film artist used the miracle of his movie matte paintings to bring to cinematic life 18th century Boston, its ship-filled harbor and homesteads in the New England villages and countryside. For Paul Revere’s ride, he later recalled, “there was no set there at all, just the center for the rider and horse. I painted all the rest of the set in there.” Peter even incorporated a surprised patriot popping his head out an upper-story window in the middle of a matte for added realism and the famed Disney touch. The imaginative designer created dozens of evocative pre-production paintings, envisioning Johnny’s world of print shops, silversmith’s establishments, and the quaint streets and alleyways of old Boston. The film’s picturesque sets were inspired by Peter’s atmospheric paintings, including a full-scale replica of the British ship Dartsmouth that was constructed on a Disney soundstage.

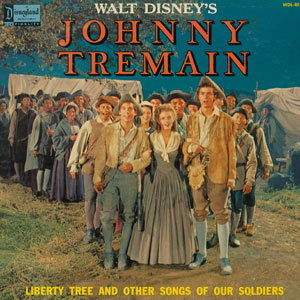

March Along With the Fifer, Boys: Songs

As they had done for “Davy Crockett”, screenwriter Tom Blackburn and composer George Bruns combined their talents and created a catchy ballad that captured the main character’s spirit in song. Though this title tune’s lively lyrics are never heard in the film (the melody is played throughout the movie’s underscore as Johnny’s theme), they tell in folksy style of the young silversmith-turned-hero character (“Didn’t like redcoats worth a hoot/And didn’t like red in any suit/Boston Town was loaded with tea/He upped and dumped it in the sea”). Blackburn and Bruns also composed “The Liberty Tree,” a jubilant march performed onscreen in celebration of the Boston Tea Party as the Liberty Boys hang shining lanterns in the branches of the great elm. The infectious song remains an unforgettable tribute to both “the strong old tree” and to the inspiring ideals of liberty.

Redcoats, Powdered Wigs and Tri-Cornered Hats: Costumes

To handle the many and varied costumes worn in this historically authentic period piece, Sound Stage 2 on the Disney lot was transformed into a giant wardrobe center/dressing room. Carpenters worked for a week to divide the mammoth stage down the middle into ladies and gentlemen sections. Rows of costumes — lined up under labels such as “Minutemen,” “British Troops” and “Townspeople” — were then made available to the large cast, including 250 extras recruited for the Lexington and Concord battle scenes, filmed on location at the Rowland V. Lee Ranch in the San Fernando Valley, 45 minutes from Disney’s Burbank studios.

Stick a Feather in His Hat and Call it Macaroni: Memorabilia

As with most Disney films, Johnny Tremain had a vast assortment of tie-in merchandise available for Tremain fans to take home. Offered was a dizzying variety of memorabilia, everything from pajamas and balloons to pencil boxes and even hand puppets. American Revolution-type playthings included a toy soldier-type playset complete with Redcoats and Minutemen figures; a bugle, fife and horn set (the red-white-and-blue instruments were actually kazoos); and a powder horn whistle. Best of all were the replicas of Johnny’s tri-corned hat, available in two styles (wool and felt) and in three sizes (small, medium, large), each with an official Walt Disney’s Johnny Tremain emblem affixed. “New colonial tri-cornered hat, destined to challenge Davy Crockett coonskin craze as new merchandising champ!” trumpeted the Johnny Tremain press book — and while the sales of Tremain’s hat didn’t quite uncrown Crockett’s cap as one of the top-selling movie-related headpieces of all time, the unique colonial chapeaus are rare collector’s items today.

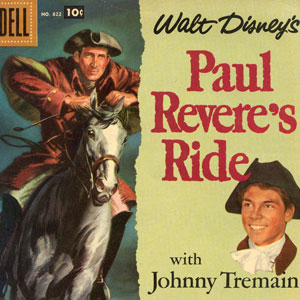

Red, White and Blue (and Other Colors Too): Comics

Johnny Tremain was translated into the comic art form to be enjoyed anew by readers of all ages. Two comic books were published: 1957’s Paul Revere’s Ride with Johnny Tremain with art by acclaimed illustrator and designer Alex Toth; and an all-new history-based adventure for the young patriot, Old Ironsides with Johnny Tremain (published in 1958), drawn by comic-book great Dan Spiegle. Fans of the funny pages could open their Sunday newspaper color comics section to discover that the weekly feature Walt Disney’s Treasury of Classic Tales was showcasing Johnny’s escapades. Written by Frank Reilly and drawn by comic-art master Jesse Marsh, the Sunday comics version of the film was featured in 58 newspapers from coast to coast, with a combined readership of 40,000,000 enthralled comics fans. Starting on April 7, 1957, Johnny Tremain ran in the color funnies for 13 consecutive weeks and came to a smashing conclusion on June 30, just in time for the Fourth of July.

It’s a Tall Old Tree: The Liberty Tree

Walt was so inspired by the story, setting and principles of Johnny Tremain that he planned to add a Liberty Street to Disneyland as a salute to Johnny’s Boston. Liberty Street at Disneyland was never to be but it was expanded into the even more expansive Liberty Square at Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World. Welcoming freedom-lovers of all ages since Opening Day, October 1, 1971, Liberty Square boasts many a Tremain touch. But the grandest sight in Liberty Square is one of the stars of the film, the Liberty Tree — a stately elm pictured on the back of the medals surreptitiously worn by the Sons of Liberty. As Walt explained, “the medallions… were the secret identification badge of the Sons of Liberty. They were called Liberty Tree Medals after the famous elm tree, which stood in the heart of Boston. The Liberty Tree was a rallying point where mass meetings were held and plans were made.” For Liberty Square, an impressive oak tree — 35 tons, 60 feet wide, 40 feet high — was found already growing on the Walt Disney World property six miles from its present site.

Moving the oak was another task entirely as it could not be simply lifted by wrapping a cable around its trunk, because vital bark and cambium layers would have been irreparably damaged under so much weight. Many ways in which the mighty oak could be transported were carefully considered until finally, holes were drilled through the massive trunk and steel rods were inserted. These rods served as grips for lifting the tree with a 100-ton crane. Carried out under the direct supervision of Imagineer and legendary landscaper Bill Evans, the transplant was a success. When the very existence of the towering Liberty Tree, already more than 135 years old, was threatened years later by an infection in the holes where the steel rods had once been, the Imagineers ingeniously grafted a second, younger oak into the base. This magnificent tree — the largest living specimen in the Magic Kingdom — was saved, and continues to thrive as a living symbol of freedom. The Liberty Tree is particularly inspiring at night when the 13 lanterns hanging in its branches (representing the 13 original colonies) shine in the dark, a luminous reminder of the ideals of the first Sons of Liberty — and Walt’s timeless tale of freedom, Johnny Tremain.