By Les Perkins

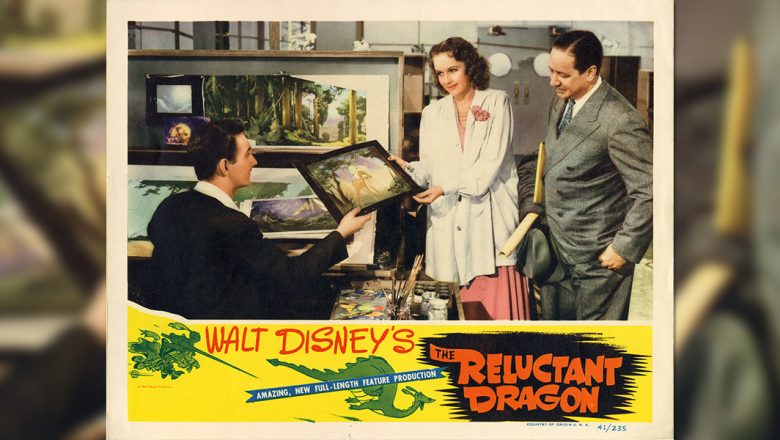

When discussing the early Disney feature films, we usually refer to the five classics: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi. But there’s actually a sixth feature sandwiched in between Fantasia (November 1940) and Dumbo (October 1941): The Reluctant Dragon, released June 20, 1941. The film provided a live- action tour through the then brand-new studio in Burbank, California, giving glimpses of the animation process—including several animated sequences—and culminating in the 20-minute story of “The Reluctant Dragon,” about a dragon that prefers poetry to fighting.

This unique feature is one of the few Disney films never reissued theatrically or edited for TV. Yet, it provides a fascinating account of the premier animation company at its zenith. Thankfully, in recent years, it has been rediscovered: first on Disney Channel, then through Home Video releases. In honor of the film’s 75th anniversary, D23 unearths seven cool facts you may not know about this innovative film.

1. Walt needed a low-budget film to generate income.

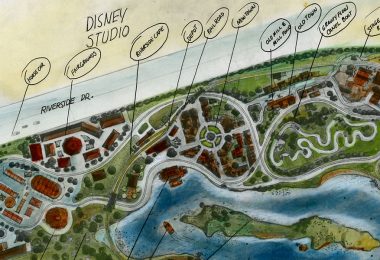

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, released in 1937, astounded the movie industry—becoming one of the most successful motion pictures ever. But despite critical acclaim, “The Concert Feature,” released as Fantasia, and Pinocchio yielded disappointing returns in 1940, due, in part, to diminished overseas markets resulting from the rapidly expanding World War II. Further, profits from Snow White were invested into building a much-needed, larger facility in Burbank, constructed specifically to accommodate Disney production methods—along with the addition of nearly 800 employees!

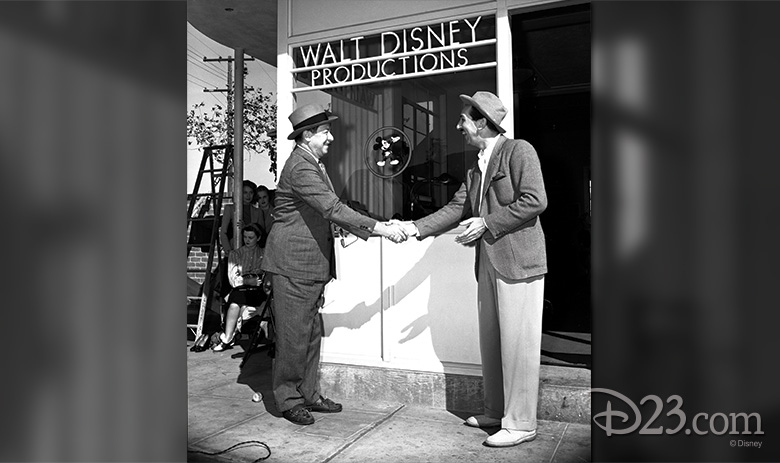

Walt wanted a relatively low-budget film for summer 1941 to help generate income, thus allowing adequate development time for the expensive features Dumbo, Bambi, and Peter Pan. “A lot of people ask me… to show how these things are made,” Walt remarked in a story conference. “We take for granted what we do every day. But to the public, it’s a mystery.”

2. The film stars the grandfather of the author of Jaws.

In that era, moviegoing included feature films, previews, cartoons, newsreels, and live-action short subjects running 10 or 20 minutes. One such M-G-M series featured humorist, critic, and sometimes actor Robert Benchley, noted for his understated dry wit. Benchley’s grandson, noted author Peter Benchley, wrote the novel Jaws and also played a cameo role in the 1975 film, playing a news reporter filing a story from the beach.

Early in 1940, Walt met with Benchley and a lively conference concluded with the idea of Benchley conducting a tour of The Walt Disney Studios, plus animated sequences. Having recently obtained rights to The Wind in the Willows (Mr. Toad) by Kenneth Grahame, Walt decided the animated climax would be a chapter out of an earlier Grahame book, Dream Days, which contains a parody on the legend of St. George and the Dragon.

3. During development, the script underwent several strange rewrites.

While still at the old Hyperion Studio, in 1937 Walt responded to a request from exhibitors in England to make a film that would help answer questions from their patrons on how Mickey Mouse is made. Al Perkins (no relation to this author) was assigned to script a short subject film called “A Trip Through The Walt Disney Studio.” Although it was a matter-of-fact narrative, it was so successful they adapted the footage to help promote Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was natural, then, that Al Perkins be the leading scenarist of this new project. The basic premise posed a huge challenge that was debated and revised for months, and he submitted a variety of treatments for the live-action structure.

A May 3, 1940 “Action Breakdown” had Robert Benchley getting on to the lot to begin a search for Walt. It even contained an overnight “Benchley Lost” sequence in which he fell asleep on the orchestra stage as Leopold Stokowski recorded “Clair de Lune” for an update to Fantasia. In the morning, Studio police found and chased Benchley all over the campus.

“I feel the plan you have submitted on the Benchley short is too much like a regular comedy,” Walt wrote in a memo to Perkins on May 6. “I think this thing should be definitely presented as a trip through the studio, and we don’t want any cheap comedy.” Walt proposed a Tuesday night meeting, which shows that long workdays were nothing new.

From surviving transcripts of story meetings, we can see that the next day, May 7, Walt already said the film needed to run at least an hour to be marketable. Aiming for an entertaining story, the team struggled with more premises and funny situations. Walt cautioned, “We’re getting away from the point, which is showing off the plant.” He later would add, “If you get into a lot of technical stuff, it wouldn’t be interesting.”

By May 21, the working title had become “A Trip Through the Studio (Benchley Picture).” Al Perkins suggested, “If he just started outside the gate and said, ‘Come on. I’m going to take you in,’ it’s just a travelogue. But it’s like a lot of people say, ‘I have a great story for Disney.’ And he would… try to find Walt and is always getting into these other things.” Work would continue on the script through August 1940.

4. One of the most famous corners in all of Disney was created for the film.

One of Perkins’ pre-production scenes has Benchley observing a street sign reading “Snow White Lane” and “Pinocchio Road.” It’s likely this morphed into the current “Mickey Ave/Dopey Drive” sign erected for this picture that remains on the lot to this day.

5. Disney employees hampered shooting.

When filming began on October 9, 1940, employees initially ruined some of the first day’s work. Most had never witnessed a film being made and pressed up against the windows to see what was going on outside.

6. Disney luminaries appear in the film.

Disney animators Ward Kimball (in a speaking role) and Fred Moore appeared in the How to Ride a Horse sequence. Norm Ferguson was shown drawing Pluto.

Walt Disney agreed on two relatively unknown RKO contract players who could be believed as staff members. Frances Gifford (Doris) went on to prominent roles at M-G-M. Alan Ladd (Baby Weems story director) became a big star after This Gun for Hire (1942).

7. Critics liked it; the public not so much.

Although many reviews were quite favorable, apparently the public was confused by what the film was. Some felt cheated it was not a fully animated story like Pinocchio. Disney storyman Otto Englander said, “This doesn’t fall into any groove. That is why it’s so hard.” The release also coincided with a bitter animators’ strike, violating the fun, happy working atmosphere depicted in the film. Sadly, Walt’s hope for a “quickie” profit-maker was not realized, and the film lost money.

Thanks to DVDs and Blu-rays, this valuable film has been rescued from obscurity. Today, we can enjoy this lovingly photographed, unusual time capsule of the great, innovative animation studio at work when it was under the guidance of Walt Disney himself. The feature (and the 1937 tour shorts) appear on the Walt Disney Treasures set (the “tins”) “Behind the Scenes at the Walt Disney Studio.” The cartoon segment has also been released on home media compilations.

Recently, a glorious re-master was provided as a bonus feature on the “Two-Movie Collection” Blu-ray of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad plus Fun and Fancy Free. And you know what? It is well worth exploring, 75 years later.