Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt Disney’s first feature-length animated film, has appeared on most of the world’s “best-film” lists since debuting in 1937. Along with Citizen Kane, it is considered one of the greatest, most influential movies ever made. All these decades later it’s still easy for viewers, young and young at heart, to be drawn into the colorfully dramatic story and its thoroughly engaging characters.

The risks Walt took artistically and financially to produce Snow White are well documented. If it failed, there would be no Disney studio and no legacy of 55 Disney animated features up to and including Zootopia (opening in March). Indeed, there would be no Pixar, no theme parks, and (yikes!) no D23.

As it turned out, Snow White was a financial and artistic hit, and its influence spread far and wide. Its success encouraged MGM, for example, to produce The Wizard of Oz, whose stylistic and narrative similarities were once advertised as “Snow White with live actors.”

Many great filmmakers, from Charlie Chaplin, Michael Powell, and Sergei Eisenstein to Federico Fellini, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg have admired Snow White. Powell, producer/director of the gorgeous The Red Shoes (1948), praised Snow White’s “controlled” color and sound. He called it “a feat not yet in the power of any other producer,” and one that “held audiences enraptured all over the world.” Fellini even emulated the groundbreaking cartoon. His script for Juliet of the Spirits (1965) describes the heroine’s cold, narcissistic mother as “the queen in Disney’s Snow White.”

Snow White has inspired generations to become animators or become better animators. A new generation will now draw inspiration from the beloved classic with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on Digital HD and Disney Movies Anywhere for the very first time! Plus, a new high definition Blu-ray™, which includes the Digital HD copy, hits store shelves February 2.

But do today’s animators, with all of the vast technological changes in animation production over the last decade, still find the film relevant?

“It was a first for everyone working on it, and though many of the artists were not quite polished, they all gave 200 percent, which really inspires me to aim high.” – Andreas Deja

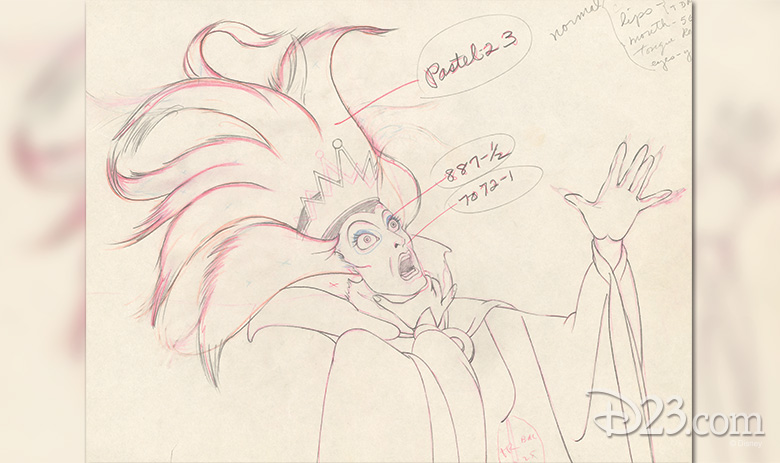

Andreas Deja, whose brilliant hand-drawn performances encompass villainous Scar, innocent Lilo, and eccentric Mama Odie in The Princess and the Frog, says Snow White still inspires because “it has something very genuine. It was a first for everyone working on it, and though many of the artists were not quite polished, they all gave 200 percent, which really inspires me to aim high.”

Deja is drawn (no pun intended) “to the dwarfs more than the straight characters because of the standout performances” of legendary animators Fred Moore and Vladimir Tytla. He praises their animation’s “gutsiness and control,” especially the latter “because the dwarfs have to be real, yet broad when they’re showing joy or are excited. Fred was the earliest master of the animation principle of squash and stretch [visualize the flexible shape of organic objects in action, as in his animation of the rotund three little pigs], which lends weight to characters and makes them real. That always impressed me, and I try to use that in my animation.”

Deja worked on a Princess and the Frog scene in which “the snake, JuJu, forms a spiral that propels elderly Mama Odie across a boat. She’s flying like the Flying Nun, and then JuJu zips in the scene and forms a spiral again to help with a soft landing. These are pretty broad actions I didn’t think we would do looking at the early storyboards. But it made it more lively, and I could use Fred’s squash and stretch principles a lot better.” By channeling Fred Moore’s gutsy, broad dwarf animation, Deja found inspiration so “those old bones can really move.”

Eric Goldberg, master of razor-sharp timing and superb comic moments in Aladdin (the gloriously fast and funny physical transformations of Genie), Fantasia/2000 (the split-second actions and reactions in the flamingo yo-yo section), and Hercules (hyper-volatile Phil), also finds inspiration in Snow White’s perfection of distinctive personality animation. “I can watch and mine great things, from the scenes where the dwarfs introduce themselves to Snow White, over and over and over again,” he says. “It is a piece of animation hard to top for sheer entertainment value and for nailing the characters’ personalities.”

Asked what he incorporates from Snow White in his work on Louis from The Princess and the Frog, Goldberg immediately answers “Appeal! I am a huge Freddy Moore fan, and everything he did had a natural charm and appeal to it. Part of the fun is the contrast: this big toothy gator who has tiny baby hands and is nervous. As with many sidekicks, he’s got to carry lots of emotional range—be funny, but you must believe he’s got a soul, some pain, and cares for the others.”

Goldberg stretches his draftsmanship by analyzing Disney classics, including Snow White. “What struck [Disney/Pixar Chief Creative Officer] John Lasseter with the early films,” Goldberg explains, “is the convincing physicality of the characters. They had believable bone structure, muscles, flab, flesh. While the forest animals in Snow White are less convincing than the dwarfs and the other lead characters, the animators were inching toward something naturalistic and appealing. Snow White was the road to what they cracked in Bambi.”

Mark Henn, an expert animator of subtle female characters, often thought of Snow White when animating Ariel, Jasmine, Belle, Mulan, Pocahontas, and now Princess Tiana in The Princess and the Frog. “Absolutely,” he asserts. “Some might argue that Snow White’s a little old-fashioned. Things happen to her and she reacts, whereas from The Little Mermaid on, our leading ladies became more pro-active. But I find Snow a very sincere, genuine, appealing character. She’s still an inspirational benchmark that I’m always looking over my shoulder hoping to reach.” He particularly loves the scene where Snow White folds her arms and imitates the most recalcitrant of the dwarfs. (“Ohhh! You must be Grumpy!”) “It’s subtle but really nice,” Henn says.

Later in the film, Snow White’s kiss transforms “woman-hater” Grumpy into a lovesick swain. “The transformation [animated by Tytla], where Grumpy puts up a big fuss when she gives him a little peck on the head and then he is overcome with emotion. And you see him melt like butter,” Henn enthuses. “Finally, he can’t hide it anymore… he really does care for her. Then there’s the complementary sister scene where animals bring the news she’s in danger. All the dwarfs run around wondering ‘what-do-we-do?’ But Grumpy’s the one with a plan. ‘Follow me, guys!’ and off goes the cavalry. His character is so rich.”

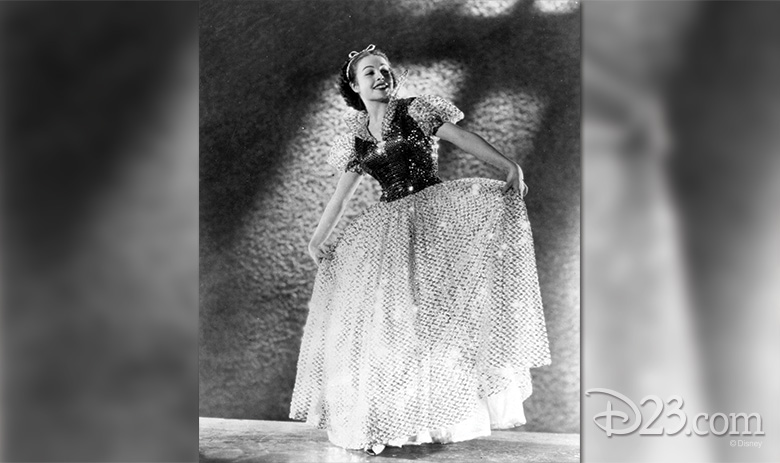

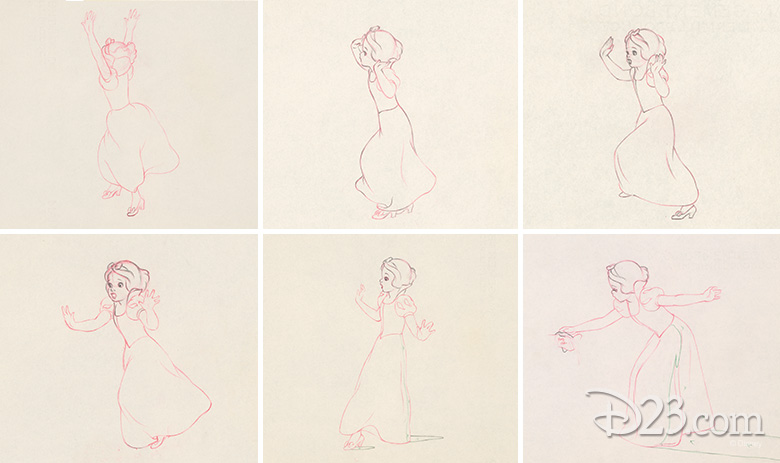

Henn’s technique uses live-action reference footage similar to how it was utilized in Snow White. After live-action is shot, blown-up stats of each frame are printed, he explains. “I go through, edit them finding the key poses of an action, basic patterns of movement. I put those on my light table’s pegs and make very quick, loose sketches over the keys, mapping out movements, some expressions that I think are worth using. In a sense, the live-action becomes my thumbnail sketches. Then I put the live-action aside, never look at it again, and animate conventionally from that point on. You animate it with all the exaggeration and principles of conventional animation to bring it to life.

“Purely from the technical side, Snow White was beautifully animated and doesn’t look rotoscoped,” Henn says referring to the technique of tracing live-action exactly without the animator’s creative input. “Rotoscoping is dead. It moves, but doesn’t have life. So however they handled their live-action reference in Snow White, I wanted to get the same results.”

Former Pixar CGI director/animator Doug Sweetland, whose 2008 short Presto was an Oscar® nominee, describes Snow White as “the blueprint for all animated movies.” He finds amazing “how full the film is, packed to bursting with detail and richness, yet how the scenes are really simple and they take all this time to work on character moments. I remember [Inside Out director] Pete Docter mentioning that here’s a movie where you have five minutes of washing up before you have dinner.”

Sweetland also observes how the story “moves on and heads to its conclusion, but things build throughout, and actions are incredibly layered. Everything is boiled down to its essence. During the song ‘Whistle While You Work,’ every vignette is like a short, where they build gags in threes. It’s not enough that the deer gets piled high with clothes; now we follow his walk out the door, and then he’s going to stumble and there are going to be 1,500 animals incorporated in that one action,” he says with a laugh.

Speaking of influencing new generations, Sweetland’s young son, Desmond, “loves that scene the most because he loves animals in particular. He can also take the witch in Snow White, and in The Wizard of Oz, but he sends us, his parents, out of the room. He has to deal with them by himself.”