On October 1, 1983, EPCOT Center premiered a thrilling new adventure, which took guests from the ocean’s depths into outer space.

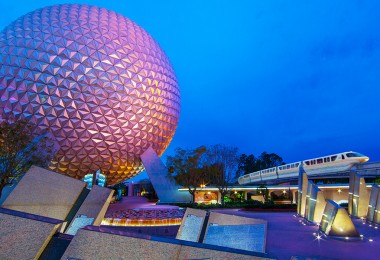

We celebrate the anniversary of Horizons, the much-beloved former Epcot pavilion that treated riders to an inspiring vision of life in the 21st century. Located where Mission: SPACE now stands, Horizons sought to present a plausible peek at future life in a world where mankind has colonized the oceans, made the deserts bloom, and established a presence in space. Although it closed in 1999, Horizons remains a fan favorite today and holds a special place in the hearts of many Disney enthusiasts. To honor its anniversary, here’s a look back at how this landmark attraction came to be.

Opening a year to the day after EPCOT Center was unveiled, Horizons was a late addition to the Epcot lineup. Not part of the original Future World concept, it was instead created from scratch for a specific sponsor. Talks with General Electric about EPCOT participation began as early as 1976; the company had long ties with Disney going back to before the Carousel of Progress‘ debut at the 1964–65 World’s Fair. Many G.E. executives from those days were still with the company when work began on Epcot Center, and they were eager to take part.

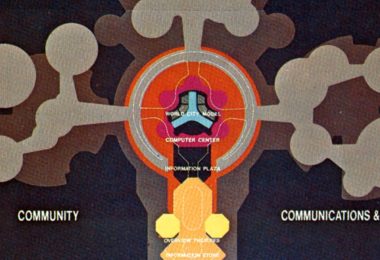

G.E. felt that since their company’s interests were so diverse, they should not be limited to existing pavilion concepts such as Space, the Land, or the Seas. Instead, Imagineers revived a concept that had been discussed previously, a pavilion of “Invention & Enterprise.” This show would depict the history of inventions and how they shaped the course of history. In late 1977, Rolly Crump and his design team were moved from working on the Life & Health pavilion to this new attraction; in later years, the show’s development would be taken over by Collin Campbell and George McGinnis.

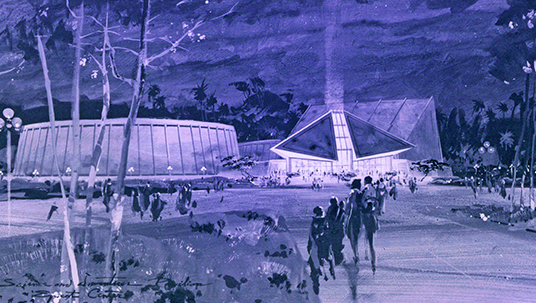

A year passed, and after much negotiation a deal was proposed by which G.E. would continue its sponsorship of the Carousel of Progress, now located in the Magic Kingdom, and sponsor a new “Science and Invention pavilion” in EPCOT Center. This would be a new Carousel Theater show with a revised design that placed guests at the center of the theater with stage sets rotating around the outside. Looking at the history of inventors and inventions, it would conclude with a “look into the future” and potential creations of science and invention.

As G.E. finalized its agreement to participate in EPCOT Center, the show concept was refined. The Carousel family was removed from the show, and it was debated whether to include Edison as narrator. Another show was outlined, entitled The Incredible Time Machine: A Journey Into The Worlds of Science and Invention, which took place in a “time-ship” theater that visited Menlo Park and other sites.

These concepts were rejected by Reginald Jones, then chairman of G.E. As Marty Sklar would later say, “They told us our idea stunk.” Jones sought an experience more forward-looking and spectacular than the Carousel of Progress. In G.E.’s words, the new show “must not dwell on the past; it must be dedicated to the future.” Despite the continuing guest popularity of Carousel of Progress, Imagineers returned to the drawing board. G.E. again considered involving themselves with the Space and Seas pavilions, as well as a new version of Science and Invention that would incorporate an IMAX theater.

A large team from Imagineering and G.E. began to develop the show; Claude Coats served as Show Designer until George McGinnis took over the role. Claude, architect Bill Norton, and industrial designer Bob Kurzweil created a preliminary layout for the attraction. After a final storyline and layout were developed, Tom Fitzgerald’s story team added humanizing details to the themes established by George, Marty, and John Hench.

Ned Landon joined the team as the G.E. representative in 1979; the company advised on everything from pavilion lighting to what a kitchen of the future might look like. Ride vehicles, made from Lexan polycarbonate, were operated with G.E. motors and drive systems, and a G.E.-made robot camera provided a live aerial view of the park to the pavilion’s corporate lounge.

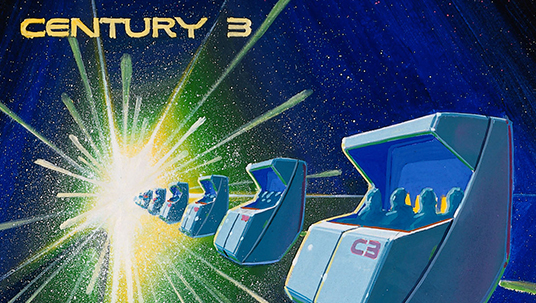

Originally called “Century 3,” the pavilion intended to show what America could achieve in its third century. From a 1980 press release:

The Century 3 Pavilion, presented by General Electric, will celebrate the envisioned technological achievements of America’s third century… the years of the 21st century leading to the U.S. Tricentennial in 2076… and what these advances will mean to each of our lives.

Visitors to the pavilion will see the ever-expanding opportunities and choices for tomorrow’s world… and the important role their decisions will play in making those visions come true in Century 3.

By the time G.E. officially signed on in October 1980, the name of the pavilion had been changed to FutureProbe. This title lasted until May 1981; as Ned Landon would famously say, “We always thought it had a rather uncomfortable medical connotation.” Several new titles were proposed, including Great Expectations, but eventually they settled on Horizons. As Landon said, “We thought Horizons was just right. There always is a horizon out there. If you try hard enough, you can get to where it is—and when you do, you find there’s still another horizon to challenge you, and another beyond that.”

Now, let’s board one of those trademark four-person vehicles for a virtual look back at a true Imagineering masterpiece.

A trip aboard Horizons began in the FuturePort—a transportation hub of tomorrow, where kaleidoscopic travel posters depicted the ride’s destinations. Designed by Gil Keppler, the area also featured the pavilion’s theme song, “New Horizons,” by George Wilkins. Richard and Robert Sherman were originally assigned to write the ride’s theme; one example, from June 1980, was entitled “Tomorrow’s Windows.” In October 1980, they wrote “Tomorrow is the Rainbow,” and this was later rewritten as “Reach for New Horizons.” Ultimately, G.E. desired something that felt less like traditional Disney fare.

The first act of Horizons, “Looking Back at Tomorrow,” examined the future through the eyes of past visionaries. A series of projections showed a man flying with the assistance of caged birds and other improbable schemes from the past. Jules Verne appeared, aboard his ship from 1865’s From the Earth to the Moon, with his pet dog and an uncaged chicken floating freely in the lavish Victorian interior.

Next came the whimsical Paris of 1950 as envisioned by French author and illustrator Albert Robida, followed by the Art Deco future of the 1930s and ’40s. While a leisurely fellow gazed out the window, a robotic butler vacuumed behind him. Upstairs, a fashionable blonde soaked contentedly in a bubble bath as she watched television. (The mammoth, black-and-white set aired a rendition of “There’s a Great, Big Beautiful Tomorrow” from the Carousel of Progress, as performed by actor Larry Cedar). Back downstairs, an automated machine gave an older gentleman a robotic haircut and shoeshine, while a robotic chef had gone haywire and was wreaking havoc in the kitchen.

Then came the films of the past; black-lit theater marquees advertising science fiction films from the early years of cinema. This idea emerged from an earlier concept for CommuniCore, the “Fantastic Flick Cinema,” which would have shown perspectives of the future from the films of yesteryear.

The Neon City’s visual style continued in “the future from the ’50s,” a panorama of jet-age futurism familiar from The Jetsons. Early plans for the scene included fully dimensional sets, but these plans changed in favor of black-lit wire frames due to budget concerns late in the ride’s development. Any savings were diminished, though, when John Hench decreed that the scene needed a large spire to draw the eye, and constructed the towering “Sky High School” to use the full height of the building.

Horizons passengers next entered the Omnisphere for a look at cutting-edge technologies of the day. Imagineers placed two Omnimax screens together for the first time anywhere to create this massive projection surface 240 feet wide and 80 feet high. The idea of using IMAX in Horizons originated with Imagineer Dave Burke; George McGinnis had experimented with curved Omnimax screens on a previous project and selected that process instead. Original plans called for an Omnisphere—formed by three adjacent screens—to serve as the ride’s grand finale; it was later moved to the attraction’s midpoint.

Eddie Garrick filmed the 70 mm Omnimax scenes, capturing subjects such as undersea divers and a space shuttle launch. Garrick’s team designed the technology required to film many of these subjects themselves, leading to several innovations; the spiraling DNA chain and space station wireframe represented the first use of computer animation in an Omnimax film. Micro-photography of growing crystals was another Omnimax first, as was the computer-enhanced Landsat photography. Low-frequency sonic transducers were placed in ride vehicles to add a rumbling effect during the film’s space shuttle launch and a bass oomph to Wilkins’ booming score.

The third act of Horizons, “Tomorrow’s Windows,” illustrated life in the 21st century. The tour began in the “Urban Habitat”—home to the attraction’s narrators; it’s no coincidence that the family strongly resembled the cast of the Carousel of Progress—right down to the familiar family dog.

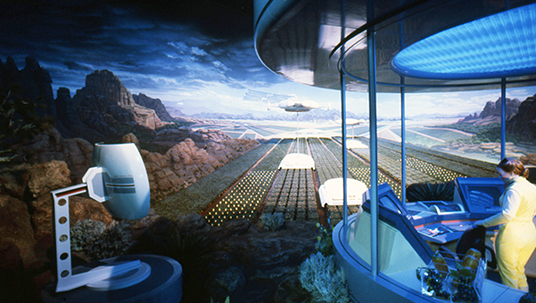

Riders found their host playing a tune on his “symphosizer,” while his wife conversed with their daughter on the holographic telephone. Passing through the couple’s hydroponic garden, riders arrived at the desert farm of Mesa Verde where the daughter and her family lived. Here, scented air was blown toward riders by the Imagineering “smellitzer” fragrance cannon. The rich perfume of oranges brought the desert orchard to life and became an attraction hallmark.

Mesa Verde, once desert, had been converted into a lush oasis; a citrus orchard stretched into the distance tended by robotic harvesters. “Helium lifters” loaded the crops for transport to market. Originally developed by Claude Coats, the scene used forced perspective to great effect in making the small space appear vast.

The technologies seen here were developed with the help of expert consultants. Dr. Carl Hodges, who also advised on The Land, provided guidance to Imagineer Alex Taylor for the futuristic farm. When Taylor originally pitched the idea of designing these genetically engineered hybrid crops (“loranges,” “pepcumbers,” and “pinanas!”), Hodges’ team thought that Disney wanted actual, living futuristic plants. They could make it happen, they told him enthusiastically, but they might not be able to have it done by opening day!

Next came the family’s Mesa Verde home. In the kitchen, father (who bore a striking resemblance to Disney Studio veteran and voice actor Pete Renoudet) was trying to decorate a birthday cake, but his son seemed more interested in playing with the voice-activated cupboards. A teenage girl in the next room, meant to be doing her chemistry homework, talked to her boyfriend via an enormous wall-sized videophone. The boyfriend, we’re told, was away studying marine biology on a floating city. Imagineer Tom Fitzgerald portrayed the boyfriend on film; the ride’s designers dubbed his Audio-Animatronics® figure counterpart in the next scene, “Tom II.”

Riders next descended into the undersea world of Sea Castle, where a class of young children—and their pet seal, Rover—prepared for a diving expedition. Two of the students were modeled on show designer McGinnis’ own children; Scott (then 5) appeared as a boy getting licked by the seal and Shana (then 7) became a young blonde girl who sat tapping her toes impatiently. Outside the floating city, diners were seen enjoying dinner through a row of bubble-shaped windows; the young divers then re-appeared, swimming underneath the vast city as the narrators touted the wealth of riches available in our oceans.

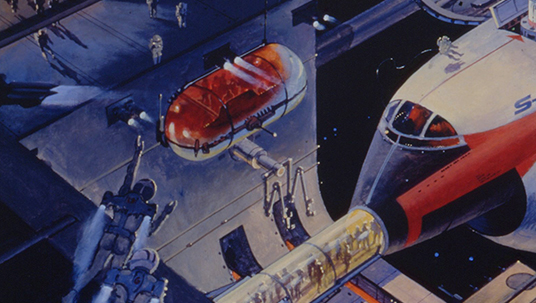

Horizons’ final destination was space station Brava Centauri. Amid a field of stars, a series of rotating stations could be seen in the distance. Consulting on their design was Princeton physicist Gerard K. O’Neill, an advocate for space colonization and designer of the “O’Neill Cylinder,” on which the designs for Brava Centauri were based. Inside the colony was a zero-g gymnasium where inhabitants could exercise in rowing or bicycling simulators; a low-gravity basketball game was also underway. From a tunnel, riders could view the rotating interior of the colony; an eight-foot spherical model was built for this effect. It required 8,000 miniature lights to bring life to Shim Yokoyama’s painting of the homes and recreational facilities of the station interior, and sharp-eyed guests might have even noticed a hidden Disneyland among the station’s features.

In the docking port, the shuttle Santa Maria had arrived. As little Tommy floated around the room with his dog, Napoleon, his father tried to retrieve the child’s stray magnetic boots. This scene transitioned to a facility where giant crystals grew in microgravity, designed with input from NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Finally, guests arrived at the party, where everyone had gathered to wish a happy birthday to the narrators’ grandson. Appearing via holophone were the narrators, their granddaughter from Mesa Verde, and her “beach-boy” boyfriend.

In the early design of Horizons, show writer Marc Nowadnick developed a post-show area called “FutureFair” to highlight G.E. products and services. Jack Welch, chair of G.E., vetoed the idea because he thought it “too commercial.” One proposal for the post-show had been a tunnel which carried guests on a moving belt past images highlighting various G.E. businesses. Having studied the mechanics of synchronizing projections to ride vehicles, George McGinnis revived the idea when his planned Omnisphere finale was moved to the ride’s midpoint. The rejected post-show idea became the famous “Choose Your Tomorrow” sequence at the end of the attraction. Now, after leaving Brava Centauri, Horizons passengers were to return home via transportation of their own choosing.

A 50-foot-long traveling screen was developed by Marty Kindel and, combined with tilting and vibrating vehicles, it created a simulator experience. Riders chose one of three possible destinations; the result with the most votes became their return route to the FuturePort. Options included a hovercraft flight through the desert, a solo-sub from Sea Castle, and a shuttle to Omega Centauri. Plans originally included a fourth film, a maglev train ride through Nova Cite, but that idea was abandoned.

Special effects veteran Dave Jones spent two years designing, constructing, and filming the miniature sequences for the films. The desert ending was the longest continuous sequence ever done with miniatures and required an 86-foot model. It was filmed in an enormous hangar at the Burbank airport, while the space sequence was shot on Stage 3 at the Disney Studio Lot. For the ride finale, the films were rear-projected onto screens with G.E. Talaria video projectors. Concerned about visual intrusion from neighboring screens, G.E. requested that flaps be added between ride vehicles.

Departing riders passed The Prologue and the Promise, a 19-by-60-foot mural by artist Robert McCall. McCall spent three months at his Arizona studio developing the piece and six months at the Disney Studios in Burbank painting the mural with the help of his wife, Louise. Said McCall, the mural represented the “flow of civilized man from the past into the present and toward the future.” Unfortunately, surveys later showed that guests weren’t associating sponsor G.E. with the attraction, and McCall’s masterpiece was replaced a few years after its debut. In its place was a beautiful rainbow corridor leading to a G.E. logo. Rotating behind a giant lens, the G.E. medallion cast off electric sparks in all directions.

G.E. eventually ended its sponsorship on September 30, 1993, and Horizons closed in late 1994. It re-opened in December 1995, as the neighboring Test Track remained under construction, and operated until January 9, 1999. In 2003, the pavilion’s footprint was replaced by Mission: SPACE, which sends guests into a thrilling journey through deep space.

While Horizons has been gone for more than a decade now, it still lives on in the hearts and memories of Epcot fans. Many a visitor can remember with fondness the smell of loranges or the visceral thrill of an Omnimax space shuttle launch. For a whole generation of parkgoers, Horizons will continue to inspire us to reach for new horizons and remind us, in the words of the attraction’s narrator, “If we can dream it, we really can do it.”