By Zach Johnson

Who is Spider-Man without the mask?

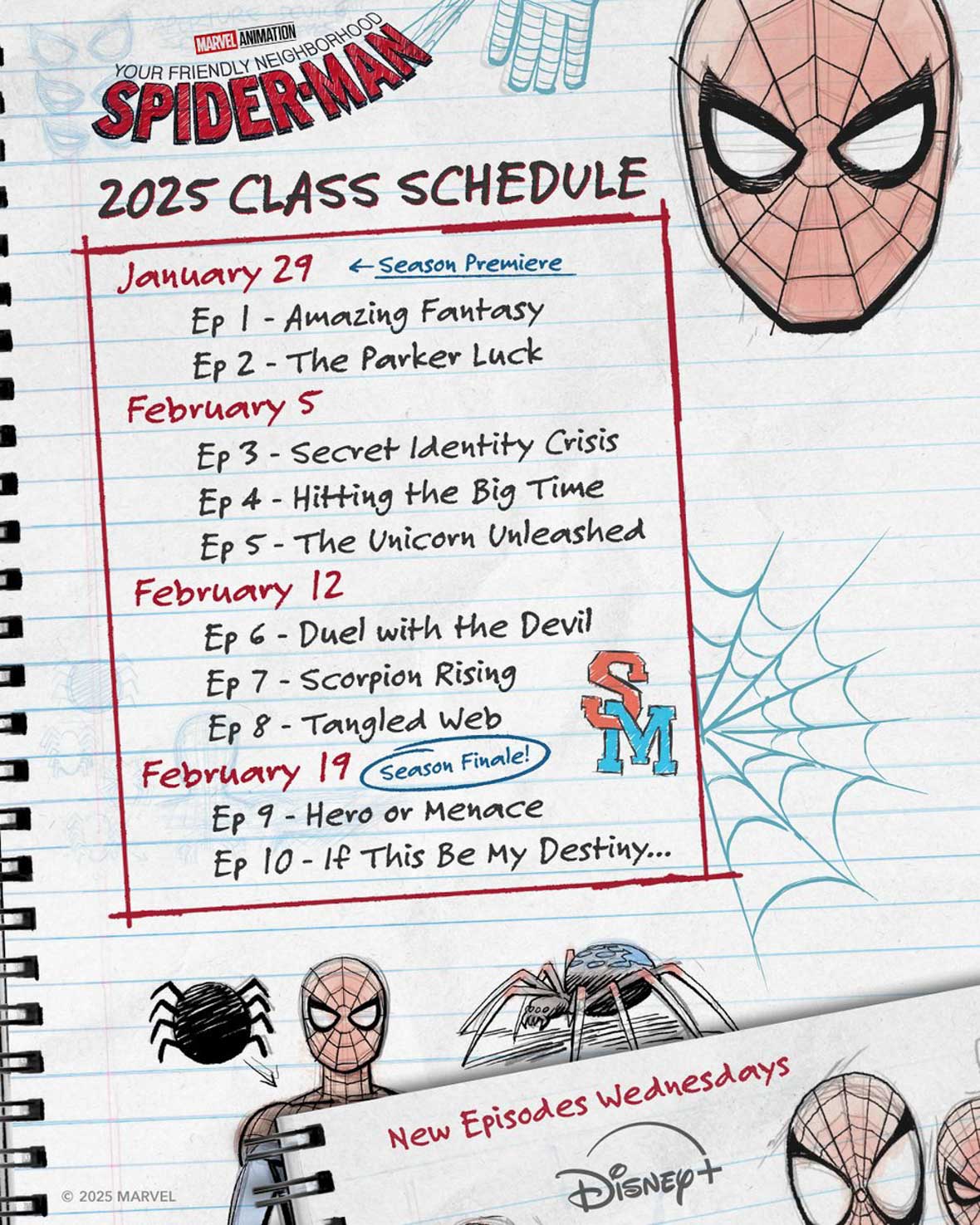

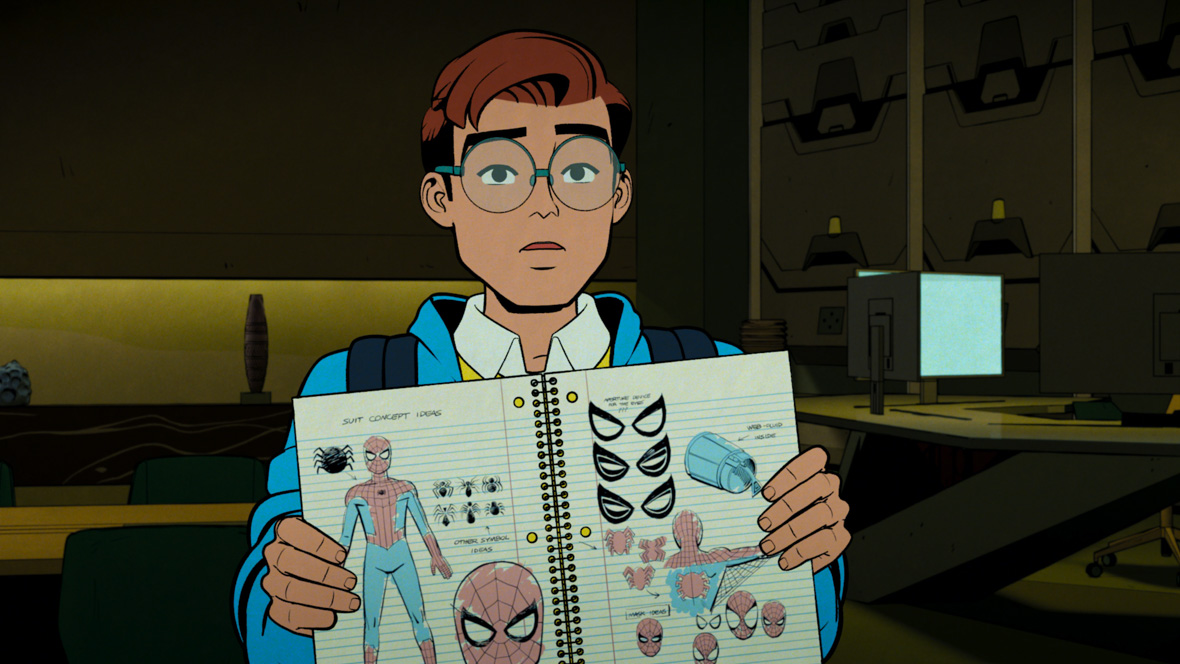

Marvel Animation’s Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man follows Rockford T. Bales High School freshman Peter Parker (voiced by Hudson Thames) on his exciting journey to become a hero. According to head writer, executive producer, and showrunner Jeff Trammel, the all-new original series — streaming exclusively on Disney+, with new episodes premiering every Wednesday — puts a fresh spin on the beloved Marvel Comics character that first appeared 62 years ago.

“We spend a lot more time with Peter in our series,” Trammel said. “A lot of the previous Spider-Man shows have been very Spider-Man focused, but for this, I felt like it was important to see who’s behind the mask and how that influences who Spidey is as a hero.”

While Aunt May (voiced by Kari Wahlgren) “has always been a constant,” the people in Peter’s life “often change,” Trammel said. “The people around him color Peter’s viewpoint.”

In Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man, Peter finds a mentor in Norman Osborn (voiced by two-time Academy Award® nominee Colman Domingo) and friends in Nico Minoru (voiced by Grace Song), Lonnie Lincoln (voiced by Eugene Byrd), Pearl Pangan (voiced by Cathy Ang), and Harry Osborn (voiced by Zeno Robinson). As Spider-Man, he crosses paths with heroes such as Doctor Strange (voiced by Robin Atkin Downes) and Daredevil (voiced by Charlie Cox) and enemies such as Otto Octavius (voiced by Hugh Dancy) and Dmitri Smerdyakov/Chameleon (voiced by Roger Craig Smith).

In the Q&A below, Trammell and Thames tease what’s in store for the wall crawler:

What makes Peter Parker — and Spider-Man — such a compelling character?

Jeff Trammel (JT): He has a lot of heart. He cares a lot. He feels like the awkward kid or the class clown, but at the end of the day, he’s always looking to do what he can to help people. I’m always trying to figure out, What is going to make Peter feel the most realistic? It’s how much he cares about these people in these situations and about doing the right thing. Even if someone is doing the wrong thing, he has the heart to see that they’re a victim of circumstance or of a bad decision, but it doesn’t necessarily make you a bad guy.

Hudson Thames (TH): It’s very refreshing to play a character who sees the best in everyone and everything all the time — who is just so hopeful. I think that reminder really resonates with people. He tries to look at the glass as half-full, and that challenges people to do the same. We all know Peter is always being dealt the most brutal of hands — but I think the fact that he always tries to be really good to the people in his life is very inspiring.

Hudson, you first voiced Spider-Man in a 2021 episode of What If…?, Marvel Animation’s first series for Disney+. What’s it been like to get to voice the character in a full season?

HT: Spider-Man was always my favorite Super Hero growing up; he’s who I resonated with the most. When I did What If…?, I remember thinking, ‘How do I semi-copy what Tom Holland did [in live-action] and honor what people know his Spider-Man to be to be?” Before this show, there was a moment where I thought I needed to rewatch what Tom, Tobey Maguire, and Andrew Garfield did — their game tapes. But, pretty quickly I realized, “No, that’s not [the best approach].” Everyone did a great job of making their Spider-Man as personal as possible performance-wise, because it’s really about bringing it back to how optimistic and helpful Peter Parker is. And with this show, I was lucky enough to have the time to dive in and figure out how to add my own voice to Peter’s. It was such a privilege.

Jeff, how did you push the limits of animation to create the series’ aesthetic? It clearly draws inspiration from Disney Legend Jack Kirby, but there are other creative choices — like a long tracking shot normally only seen in live-action — that feel fresh and new.

JT: Our lead character designer, Leonardo Romero, has a knack for taking that very classic art style and modernizing it. There are so many talented people on our team and on the Marvel Studios Vis Dev team, too. We also worked with our vendor studios, Polygon Pictures in Tokyo and CGCG in Taipei, to create a really interesting mixture of 3-D, CG with a 2D look. It’s given us the opportunity to sort of bring the comic books to life. They’ve been really innovative, and we’ve been able to work together to make something really special. And I think it stands out amongst 60 years of different Spider-Man incarnations.

Throughout the season, audiences will see Spider-Man encounter a handful of other New York City-based heroes, from Doctor Strange to Daredevil. What were your conversations with Marvel like regarding which characters you could include and how?

JT: It was really just about following where the story took us, knowing what we wanted to do, and seeing who fit that story. There are so many characters that we could have used, but no one at Marvel ever said, “Don’t use this character.” No one ever said, “We’re reserving this person.” Marvel has been very open and supportive in terms of using its characters. Yes, Doctor Strange and Daredevil have a lot of history with Spider-Man, but our show is adjacent to the main Marvel Cinematic Universe timeline, so it’s a kind of perfect mixture of being one universe over. We’re able to tell these stories but still have touchstones of what’s happening in the wider world.

HT: And I have to say, I’ve had so much fun getting to work with people like Colman Domingo and Charlie Cox. I have been trying not to fanboy out the whole time, basically.

The series has already been greenlit for more episodes, and the Season 1 finale sets up surprising storylines for nearly every character. Which are you most excited to explore?

JT: A lot of those teases are there because they’re all so exciting to explore. I look at Season 1 like we’re building this world and we’re setting the board. In Season 2 and future seasons, now we’re playing the game. That’s really exciting to me — to dig into those stories and see where we can push this universe even further now that we’ve earned the trust and the love of the fans with these characters. We can take them on a bigger journey.