By Ross Anderson

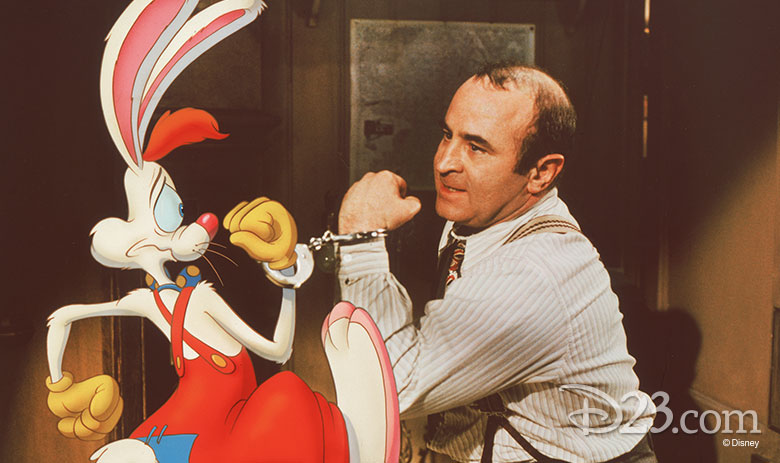

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was released under Disney’s Touchstone banner and was a combined production of Disney and Amblin Entertainment, which was founded by Steven Spielberg. The film’s story takes place in 1947, opening with a typical mid-century cartoon short. As the short concludes, we find that the “toons” are just acting out roles in a studio production, and they actually lead their own lives in Toontown—often with more zany convolutions than they display in their scripted shorts. A down-on-his-luck private detective, Eddie Valiant, is drawn into a murder investigation and a citywide conspiracy. The look is film noir, the gags are broad, the acting is sublime, the writing is clever, the animation superb. More than that, the combination of animation and live-action is totally believable and remains astounding to this day. Thirty years later, Who Framed Roger Rabbit remains a fan-favorite, and to celebrate the film’s anniversary, we’ve rounded up some animated facts and anecdotes.

1. Easter Eggs For Quick Eyes

Roger Rabbit pulsates with unforgettable scenes, characters and cinematic legerdemain, and each fan finds their own joys, favorite scenes, favorite quotes, and the fun of searching for the hundreds of Easter eggs embedded in the film. Particularly cool are the references to members of the production crew that have found their way onto graffiti, store signs, and billboard notices in the Toontown segment. Caricatures of production crew members are on billboard notices for Br’er Baer (Dale Baer) and Gregory and his Rubber Band (Gregory Hinde); and Christine (Blum), Cindy (Finn), Jane (Baer), Gisele (Recinos), Randy (Fullmer), and others involved with the film are memorialized on Toontown store signage—kind of like the acknowledgment given to key Disney contributors on the windows of Main Street. There must certainly be others that are less obvious.

There is also an assortment of cartoon comic devices strewn about Toontown: banana peels, falling anvils, and rubber chickens. Of course, rubber chickens show up elsewhere in the film; when Daffy Duck is maniacally playing in the “dueling pianos” segment, he’s wearing boxing gloves initially, but as he continues, his hands come up with a hammer and ice cream cone and then with rubber chickens. Part of the fun of watching the film is to identify the many references to animated shorts and features from the past. Sure, lists of Easter eggs can be found on the Internet, but it’s more fun to discover them for yourself.

2. Out-of-this-Galaxy Effects

Although Tron had been made a few years earlier, digital special effects had not yet found their way into film in a serious way, and all the special effects in Roger Rabbit were done with optical printers, puppetry, stop-motion animation, and clever gadgetry. Astoundingly, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) did more special effects for Roger Rabbit than were done for Star Wars.

3. A Legend Gets His Start

Andreas Deja got encouragement from Eric Larson to pursue a career in animation and was eventually hired at Disney. During the production of The Black Cauldron in Burbank, Deja was put in an office with Tim Burton, partly to coach Burton in classical “Disney” drawing. Of course, it didn’t work out that way, and although Burton didn’t quite fit the Disney mold, the freedom he was given to develop projects on his own has ultimately given us Vincent, Frankenweenie, and The Nightmare Before Christmas.

The experience of The Black Cauldron proved to be difficult for many of the young animators at the studio. The Nine Old Men had retired by that time and there had been a changing of the guard. When given the chance, Deja jumped at the opportunity to be one of the supervising animators on Roger Rabbit at the new studio Disney was establishing in London.

4. The Animation Made ’Round the World

All of the people working on Who Framed Roger Rabbit knew that they were working on something very special. It was a grand adventure for the American and Canadian expatriates, as well as for the British and European artists. It made for a collegial atmosphere and the extra enthusiasm of being part of something historic. The animators would routinely work long hours, grab a pub dinner at the Edinburgh Castle Tavern on Delancey Street in Camden Town, then go back to work in the evening. Also, the production and coordination with the live-action footage was complex and time-consuming. In spite of the long hours, the London crew was as risk of not having the film ready for the scheduled summer 1988 opening. Of course, this was before the advent of computers in the animation process.

A satellite animation unit was set up in Glendale, under the supervision of Dale Baer, and was focused primarily on the Toontown sequence. It functioned independently, and production could be coordinated and artwork shared through “high-tech” means such as FedEx and fax.

5. A Reason to Smile

On March 18, 1988, a wrap party was held at the Barbican Centre in London. The entire London crew was there for the celebration and was treated to a magic act by the producer, Frank Marshall, and a thank-you speech by director Bob Zemeckis. The song, “Smile, Darn Ya, Smile,” was planned for the gathering of Toons during the “iris out” at the end of the film. The song had already been recorded by professional singers, but the producers felt that a more raucous crowd sound was required. Sound equipment was set up at the wrap party and the crew was asked to sing, “Smile, Darn Ya, Smile.” Each member of the crew was paid the amount of one pound (somewhat more than one dollar) for their singing contribution to the film, and everybody had to sign a waiver!

This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in the Fall 2013 issue of Disney twenty-three and was modified for D23.com.