Bob Gurr remains a man on the move while his creative accomplishments as a Disney Imagineer continue to transport people around the world… literally.

Energy. That’s the first thing you sense about Bob. This is abundantly evident during a visit on the shaded patio of The Big D commissary at Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) in Glendale, California. As we speak, Bob’s laid-back demeanor and sunny disposition belies the pride he so clearly has in his accomplishments. Adding a touch of nostalgia to the surroundings here are reminders of Bob’s past design efforts: Skyway buckets and a PeopleMover car. “If it moves on wheels at the Disney parks, I probably designed it,” he says, grinning.

You get a guy like Walt once a century. We got to be the orchestra, and he waved the stick. It was so inspirational.

A 1952 graduate of Arts Center College of Design in Los Angeles, Bob grew up in the shadow of Grand Central Air Terminal, Southern California’s premier airport in the 1930s and ’40s, which these days just happens to be part of the site of the Disney Glendale campus. Watching the chaos of a busy airport—planes roaring overhead, sleek cars coming and going, and skirmishing mechanics making the aviation magic happen—whetted young Bob’s appetite for industrial design.

His numerous innovative and iconic designs for Disney—Autopia cars, the Monorail, PeopleMovers, Main Street, U.S.A. vehicles, Matterhorn bobsleds, and Mr. Toad cars, to name a few—led to his receiving the Themed Entertainment Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1999. Five years later, Bob was officially recognized as a Disney Legend.

D23: Becoming a Disney Imagineer was truly a case of serendipity for you, wasn’t it?

Bob Gurr: While visiting Arts Center one day, sometime after graduating, I met an acquaintance with the school’s job placement department who asked me if I did any outside work. I had a day job and said “Yes,” but, really, I hadn’t done any. The next morning, he phones and tells me to be at the Disney Studio in 10 minutes. So I walked out of my job, smiled at my boss, and started work with Disney. It was the second week of October, 1954.

What was your first job with Disney?

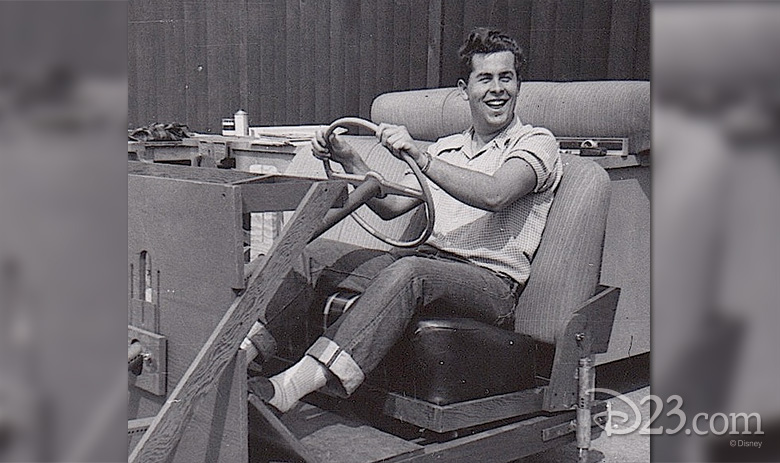

Designing and building the Autopia cars in time for the opening of Disneyland.

How did you meet Walt?

A few weeks after starting with Disney, a group of us were huddled around an Autopia chassis and this old guy walks up, unshaven, funny short tie and Roy Rogers-style western belt. I thought this was the father of one of the night guards. We talked at great length about the car. When this guy walked away, everyone said, “See ya, Walt.” I thought, “Was that Walt Disney?” So I was never formally introduced. He was just another person in the midst of the conversation. And it was not until my third week, when Walt asked me questions about my books on car design, that we officially met.

Was there tremendous pressure to get the cars completed in time for the opening?

I would not call it pressure; it was more like enthusiasm for a new idea. There was so much excitement around Walt and so much going on. It wasn’t pressure—because if you’re doing something out of your own enthusiasm, you don’t see it as pressure.

What was Disneyland’s opening day like for you?

I was just trying to keep all the Autopia cars running, on the attraction and in the parade! We had 20 cars running but the carburetors kept locking up. I was constantly kick-starting the cars; once they were running they were OK, but waiting for the go-ahead to be in the live televised parade was the hardest part.

Isn’t there a story about Walt gifting you a garage?

After Disneyland opened, we had a lot of trouble with the Autopia cars. The majority of them were failing, and no one had figured out the support side of the attractions. I had been with my own tools, repairing the cars on-site. Walt came by, looked at the whole scene and asked, “What do you need?” I told him we needed mechanics to work on the cars, and we didn’t have any kind of facilities. In less than an hour, here comes this tractor dragging an old building and the driver says, “Here’s your damn building. Walt told me to bring it to you. Where do you want it?” We had mechanics the next morning.

What’s the difference between the Autopia experience of 1955 and the experience of today?

In one way, it’s exactly the same. When kids are growing up, they can’t wait to be tall enough to drive them. The current car was designed in 1967 with a better engine and more electrical components. We used the exact same car for Walt Disney World’s Tomorrowland Speedway. The bodies at Disneyland were redesigned in 2000, but the technical part of the cars is pretty much the same.

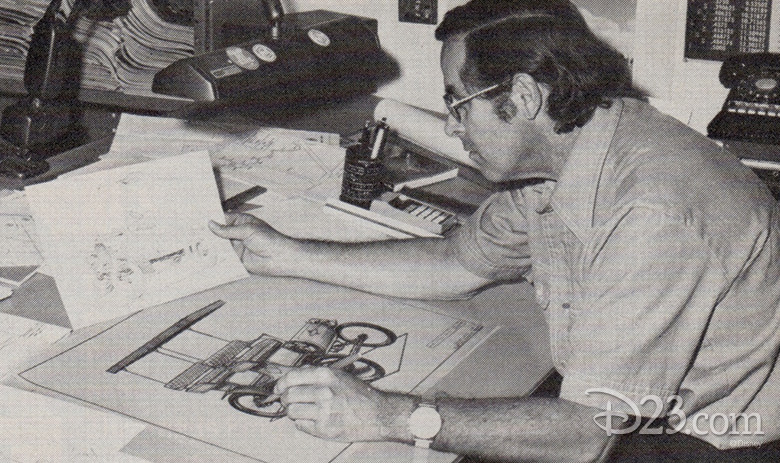

What influenced your design of the Disneyland Monorail, the first daily operating monorail in the western hemisphere?

Walt had returned from a trip to Germany and had photos of a monorail train that hung from a beam. It was very ugly, but he was excited about the idea. The whole thing looked like a loaf of bread with a slot sitting on a stick. I figured out how to hide the rail—you put a Buck Rogers spaceship on top of the beam with the point in the back—a sled runner in the front. It hides the fact that it’s a rectangle shape. The Monorail is like the California Zephyr; if you go to Disney California Adventure you can see the Zephyr’s fluid design influence. Another influence was the 1937 Greyhound Bus that was called the Silver Line.

You have said that the Disneyland Monorail is not a full-size train. What do you mean?

The Monorail is a smaller scale; there was nothing specified by Walt or anyone on the size of anything. In those days, when Walt said he wanted something, you immediately figured it out in your head and hoped it would be what Walt wanted.

Do you have a favorite Monorail design?

It’s like having six grandchildren and you’re asking me to pick one? They are all different for different reasons. A Learjet inspired the Mark IV design for Walt Disney World—the windshield, the color, the smoothness. When we were flying in the Disney jet, we stopped for gas one time in Kansas. Another corporate plane would land and a red carpet would be rolled out and a girl would walk out with flowers. I thought to myself, I want that feeling when people go to Walt Disney World. I want people to feel special when the Monorail comes to pick them up.

Like Mickey Mouse or the castles in Anaheim or Orlando, the Monorail simply screams “Disney.” What aspect of the Monorail are you most proud of?

That they have been operating efficiently 99.99 percent of the time since 1959!

Speaking of 1959, didn’t you have a funny thing happen to you on the opening day of the Monorail at Disneyland?

We had assembled the Monorail only two weeks prior to test and adjust, which now normally takes a year. Every day, the train went a little further and every day it broke down. The day before the Monorail was going to be dedicated on live television, the train did go around once without failure. The next morning, Walt is with Vice President Richard Nixon, and his family is up on the station platform for the dedication and Walt is showing off his Monorail. Walt said that he liked to drive the steam locomotives but because this is a modern train, “Bobby” will pilot. So, Walt gave the green light and without notice, we drove off… we just took off. Nixon realized that the Secret Service had not gotten on the train. When we came back into the station, the Nixon girls said “Let’s go again.” This time the Secret Service agents are trying to jump in the train as I drive right on through the station much to Nixon’s bemusement! We came back into the station and got out. Our German engineer came running up to me, yelling in a thick German accent, “You crazy Disney people! Just because you get the train to run once, you put your Vice President on this thing without knowing how it really works! You are a crazy person!”

Today all major tubular steel roller coasters can trace their design roots back to the Matterhorn Bobsleds at Disneyland. How did you earn your lederhosen on this project?

When Walt returned from making Third Man on the Mountain in Europe, he tells me that we are going to put in a Matterhorn with not just one but two roller coasters inside and that I’m to design the bobsled cars and design the track for the roller coaster. Fact of the matter is, I hate roller coasters! We had a year from start to the opening day. We built the fastest way out of necessity: We bent the track pipe and used wheels to speed up or slow down the bobsleds. This had never been done before. My son and I were the first riders on the Matterhorn. We had hay bales around the track and sand bags in a little test car that was ugly. Walt was there and said, “You designed it, you ride it.” After we survived the first few runs, all the executives rode and the ride got faster and faster.

You started working for Walt around the time that he became a TV personality. Were you ever in the park with him when he encountered fans?

In the park, he was a fast walker and he always made a point to keep moving. He always had a lot of guests with him, which made it hard for him. They slowed him down; if he stopped to sign one autograph, he would get surrounded. This is what led to the idea of having a runabout electric car for Walt to drive and take his guests around in. I came up with the 1903 Oldsmobile that was cuter than a bug’s ear. I actually selected the colors for each of the cars.

You worked on the fabled Flying Saucers at Disneyland. What was it like to ride it?

The Flying Saucers are a little bit hard to understand. It was like human air hockey.

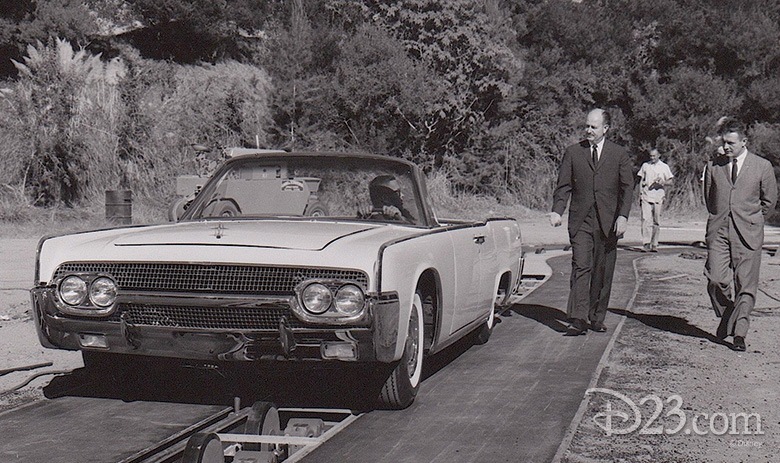

You worked on all four of the Disney shows for the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair. Which was your favorite?

I think the Ford Magic Skyway. I recall being at a meeting with Walt and Henry Ford II. We wanted to use the booster brakes like on the Matterhorn, and there was this Ford finance guy telling Walt not to do it. He wanted to use an assembly line sort of thing. During the conversation, the finance guy started heavily objecting and, in mid-sentence, Henry Ford kicked him under the table and the finance guy immediately changed his tune!

Is it true that Walt was once accused of killing President Lincoln?

Oh yeah, that’s right. We had a hydraulic overload problem prior to the World’s Fair opening. Walt was showing some lady the figure and a hose broke and it got on the shirt and turned it red. The lady started yelling at Walt—how dare he reenact the killing of President Lincoln! Walt wasn’t too happy.

You traveled extensively with Walt as he did research for his original vision of EPCOT. Did you spark to the idea of EPCOT?

EPCOT? I thought “Apricot!”… what the heck is it? I don’t ever remember being enthusiastic, and I don’t recall anyone else being enthusiastic about it because we were kind of getting thrown into it. It seemed like a cool dream, but the dream of utopia is a great first sentence and disintegrates when you get into the paragraph.

When most of the Disney Legends discuss working personally with Walt, they have a tendency to get a little wistful. Why?

You had to know Walt. I can understand the wistfulness. You get a guy like Walt once a century. We got to be the orchestra, and he waved the stick. It was so inspirational. Outside, the public viewed him as Wizard Disney, Genius Disney, and Walt Disney, but to us he was just Walt.

You designed so many things that are iconic to Disney. Which one sums up Bob Gurr the best?

The Monorail. It represents the feeling that there is a big beautiful tomorrow. I hear from adults about when they first saw it or when they first rode it. When you see a sleek monorail going across high on the beam with the sun setting behind it… I still get a little teary-eyed when I talk about it.

You were often asked to create things that didn’t exist. Isn’t that a difficult position to be in?

No, because it’s easier if it doesn’t exist. You don’t waste any time researching. You just get cracking and go and figure it out.

You’re part of the first generation of Walt Disney Imagineers. In your opinion, what makes a great Imagineer?

A person that truly is curious about everything, especially things they don’t know anything about and are not truly interested in.

It’s really as easy as that?

Simple as that.