“As much as he wanted things his way, Walt Disney recognized he needed people on his staff that would challenge, disagree, and go against him in his own animation department,” Disney Legend Floyd Norman recalled.

“Guys like Walt Peregoy knew that in order to keep animation alive and thriving, there was a need to move forward—even if it was over the objections of the boss.”

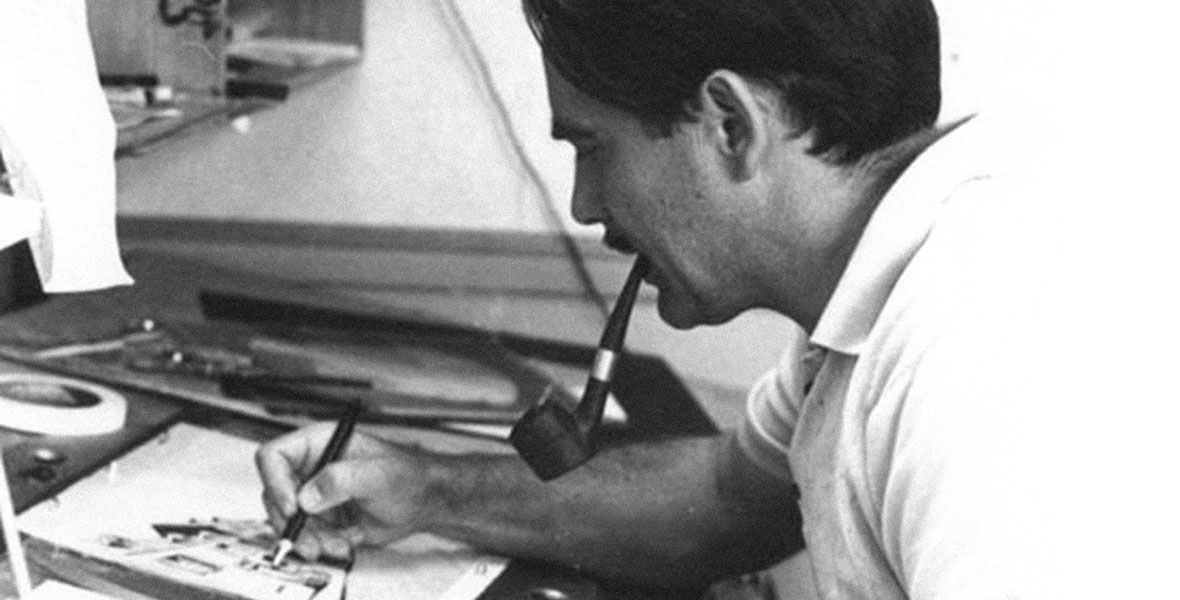

Born Alwyn Walter Peregoy in Los Angeles, California in 1925, Walt spent his early childhood on a small island in San Francisco Bay. He was nine years old when he began his formal art training, attending Saturday classes at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Berkeley. When he was 12 years old, Walt’s family returned to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in Chouinard Art Institute’s life drawing classes. At age 17, he dropped out of high school and went to work for Disney as an in-betweener.

In 1942, he joined the Coast Guard, and served for three years. After World War II, he continued his art education, studying at the University de Belles Artes, San Miguel de Allende in Guanajuato, Mexico, and with Fernand Leger in Paris.

In 1951, with a young family in tow, Walt returned to the United States, and resumed his career with The Walt Disney Studios. Initially, he served as a designer and animator on Peter Pan (1953) and Lady and the Tramp.

Even on these more conventional projects, Walt’s personal style began to surface. “I always asked myself,” he later recalled, “how come their idea of realism is completely contradictory to a duck or a mouse or a baboon talking? That’s not realism. It’s freedom. So, why does a flower have to be put next to an airbrushed rock?”

Walt’s unique style meshed well with that of his contemporary, stylist Eyvind Earle, and their work on the Academy Award®-nominated short Paul Bunyan was a departure for Disney. “My style was unusual for Walt Disney, but he tolerated me,” Walt later said. Although, since he was “tolerated” for 14 years, the artist sheepishly admitted, “I had to be doing something right.”

Walt was lead background painter on Sleeping Beauty, before embarking on his most ambitious, intelligent, and personal effort.

“To this day, Walt Peregoy’s color styling in One Hundred and One Dalmatians remains a fine example of how color can be used creatively in animation while serving more than a merely decorative function,” said modern animation authority Amid Amidi.

Walt continued at Disney on the features The Sword in the Stone, Mary Poppins, and The Jungle Book, after which he spent several years with Hanna-Barbera.

He returned to Disney in 1977, contributing his unique view to the design of EPCOT Center, where his influence included architectural facades, sculptures, and murals for The Land and Journey Into Imagination pavilions.

Later in life, Walt worked mostly in oil and pastels, and his work has been shown at the National Gallery, the Library of Congress, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The same muses that drove his innovative work at Disney still spoke to him. “I listen for what should be there,” Walt reflected. “If you really love to express yourself visually, it’s a shame if you don’t do it. If you keep ignoring the muse, it disappears.”

Walt Peregoy passed away on January 16, 2015.