By Jim Fanning

Released on April 12, 1996, Disney’s James and the Giant Peach has been satisfying audiences’ appetites for fantastical filmmaking for 20 years. Ripe with adventure and blossoming with fun imagination, this delicious stop-motion animation/live-action film—based on Roald Dahl’s best-selling book—tells the tantalizing tale of James Henry Trotter. Life is the pits for the young English orphan until he finds a secret entryway into an enormous peach that takes him and a newfound family of human-sized insects—Centipede, Earthworm, Ladybug, Glowworm, Grasshopper, and Miss Spider—on a fabulous, adventure-filled journey. To celebrate this fanciful film’s 20th anniversary, Disney historian Jim Fanning harvested some fruity factoids and insect info from this peach of a movie.

Before James was Made, Roald Dahl Knew Disney (as in Walt)

Before he became an acclaimed children’s literature author with the publication of James and the Giant Peach in 1961, writer Roald Dahl was a fighter pilot for the RAF during World War II. Dahl wrote a story about the mythical mischief-makers of the air, the Gremlins, and even before the story was actually published in a British magazine, Walt Disney himself invited the author to visit the studio in 1942. Dahl stayed for two weeks helping Walt and his artists to develop an animated film that was ultimately shelved. A Gremlins book was published the following year, however, with illustrations by the Disney artists. (Some have surmised that the Willy Wonka character in Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was inspired by Walt.) Dahl turned down many offers to make the book into a movie before he died in 1990, but when his widow, Liccy (Felicity), was approached by director Henry Selick about turning James into a stop-motion feature, she was so impressed with Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), which Henry directed, that she agreed. Roald’s daughter Lucy, who served as an advisor, said, “Henry didn’t just walk in and say, ‘I’m going to do this film the way I want to.’ He studied my father’s work, he asked questions, he looked through my father’s files in England—he really worked to get it right. And he did it. It’s better than I thought it ever could be.” (Two of Lucy’s daughters have cameos in the film.)

The Film Characters were Designed by Another Famed Children’s Book Creator

Renowned children’s book illustrator Lane Smith was the film’s conceptual designer. “Contractually, I was only supposed to do 20 inspirational paintings and designs, but I ended up doing 50. It was also supposed to be just a six-month job, but I stayed on for a couple of years just because it was really fun. I wasn’t obligated to do any more work, so I kept coming up with excuses to come back.” A Caldecott Honor Book artist, Lane opted to make James’ companions appear more surreal and whimsical and not quite as insect-like as they appeared in the original book illustrations. Disney published Lane’s concept paintings in a storybook adaption of the film. At the same time, Roald Dahl’s family was so impressed with Smith’s artwork that they commissioned him to illustrate a new edition of the original James and the Giant Peach book.

Casting James Required a Person and a Puppet

Cast as the perfect young actor to portray James in the film’s live-action portion and to perform his voice in the animated scenes, Paul Terry was selected from 500 boys after auditioning several times for the part, both in England and the U.S. The James puppet for the stop-motion sequences was based on Paul’s appearance. “When you turn a human character into a puppet, there are things you have to do to make it fit into the puppet world,” explained character department manager/supervisor Bonita DeCarlo. “James’ eyes were the biggest problem for us initially because in the early designs they were too realistic looking and it made him look spooky. We eventually settled on button-style eyes which added a much warmer look to the little James puppet.” Forty-five different articulating heads were made for the James figure because he had to “act” so many expressions.

Creating an Imaginative Cast of Insects Took More Than a Magic Crocodile Tongue

To create James’ creepy-crawly but loving companions required two years of painstaking work performed by a team of 130 people. Once these weirdly wonderful characters were sculpted, a complicated process was undertaken to build the 180 puppet characters. Tom St. Amand was in charge of custom-making the armatures or metal (steel, aluminum and brass) skeletons that enabled the characters to be animated with such a wide range of motion and expression. “I look at the character sketches and try to figure out how things are going to articulate. For the bugs, we studied insect photos and then caricatured them. A real centipede has 144 arms so we took some artistic license with our character and pared it down to 12. Even the earthworm, which looks relatively simple, has 10 joints to help him get the movement he needs.” Thirty-two department supervisors were responsible for making the latex rubber forms that were baked around the armature. Once the casts were finished, the puppets were sent to fabrication where costuming was added and painting was applied. To meet the needs of the production, 15 puppets were created for each of the seven main characters.

You Might Go Buggy Giving Life To the Puppets But It’s Never Boring

Once the puppets were built, the animators provided the performance. Selick assembled a core team of 17 exceptional talents, with an additional six animators contributing to the film during the course of production. Animator Anthony Scott had the distinction of having the two longest shots in the film: Miss Spider tucking James into his web-bed (one of the best loved scenes in the film) and a portion of the musical sequence “That’s the Life” in which Ladybug spreads her wings by kicking up her heels. Each required three weeks of intense concentration. “One of the shots I did took six days to complete 12 seconds of screen time. I had already planned out the whole shot, but I knew that I was only going to be able to do two seconds each day so I just concentrated on those two seconds. Watching it come to life is amazing to me. It’s never boring.”

The Voices Were Performed By a Peach of a Cast

Bringing the bugs to vocal life was an eclectic cadre of actors, including Richard Dreyfuss (Centipede), Jane Leeves (Ladybug), Simon Callow (Grasshopper), David Thewlis (Earthworm), and Susan Sarandon (Miss Spider). “I’ve always loved the story of James and the Giant Peach,” Sarandon once said. “It has a special meaning about empowering yourself and says that your fears won’t have any power unless you give in to them.” For many of the voice actors, singing had not been among their previous performing skills but they enjoyed singing the film’s specially composed songs.

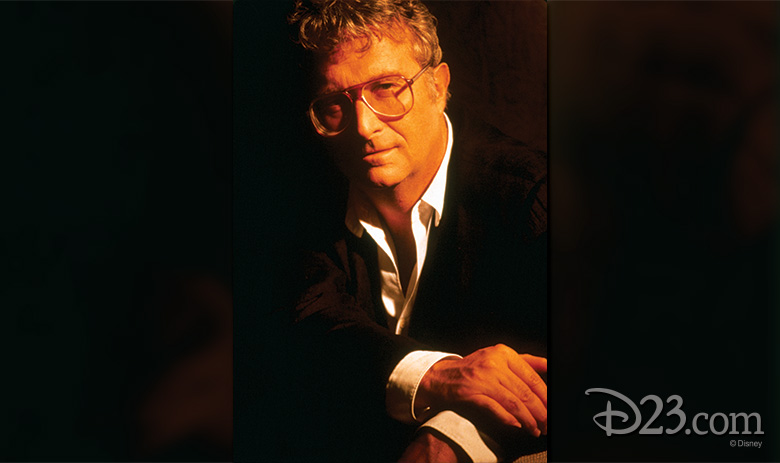

Randy Newman Composed the Songs But Had a Special Lyricist For One of the Tunes

At the same time he was creating music for Toy Story (1995), Grammy Award-winning composer Randy Newman was penning songs and score for James and the Giant Peach. He wrote five tasty songs, including “Eating the Peach.” For this musical paean to feasting on peaches, Randy turned to the best possible source for lyrics: Roald Dahl. The words came from the original book and in the film are set to Newman’s composition. “It’s basically a good old 1890 English vaudeville number with a real sloppy sort of a foodfest going on in the background,” said the songwriter, whose efforts earned the film an Academy Award® nomination for Best Original Musical or Comedy Score.