By D23 Team

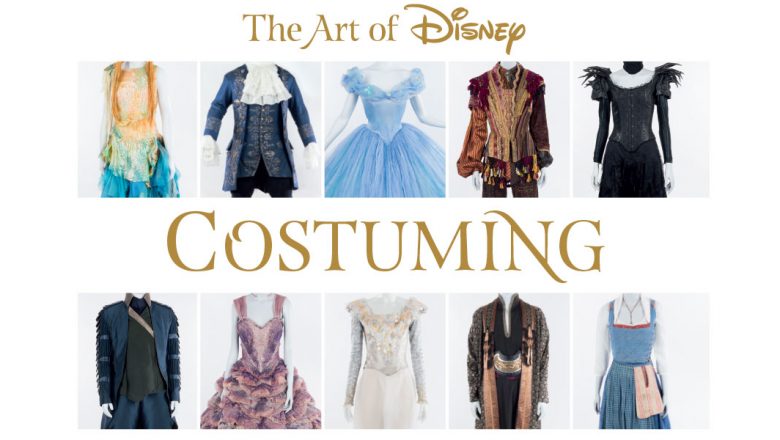

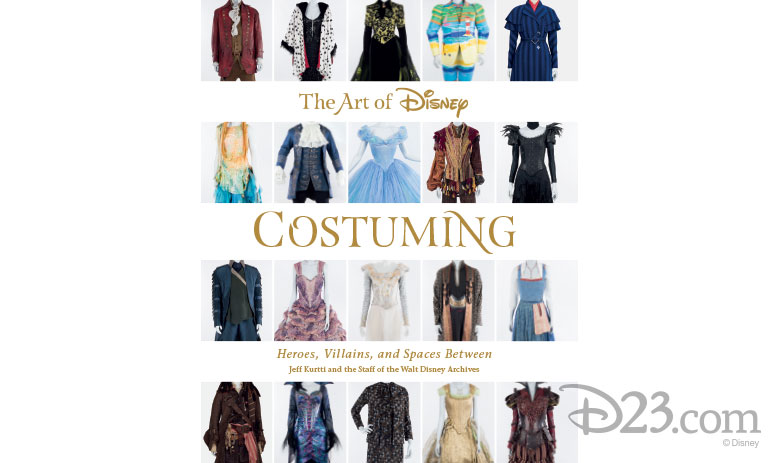

Within the pages of The Art of Disney Costuming: Heroes, Villains, and Spaces Between, an elegant and adventurous array of dresses, uniforms, and other attire is a feast for the eyes and a fascinating examination of pure craft and of the brilliant, creative minds behind it.

The collection by Disney historian and author Jeff Kurtti begins with a summation of the costumes created for Disney animation, early live action, and television, along with show wardrobes sported at the Disney Parks by Audio-Animatronics® figures and cast members. The next section details a timeless case study: Cinderella’s ball gown. A diverse group of designers has been called upon over the years to address and improvise the creative and practical needs each time the fairy tale Cinderella has been reimagined. At last, the full galleries (organized by the character archetypes of heroes and villains, and those complex, always interesting, “spaces between”) showcase costumes across more than 30 Disney films.

The book will be out this September from Disney Editions and available in advance exclusively at D23 Expo. Many of the costumes featured in the book will also be displayed at the all-new D23 Expo exhibit “Walt Disney Archives Presents Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume.” Here, Jeff Kurtti provides D23 some highlights from inside this one-of-a-kind backstage view of remarkable works of art:

Dressing Disney: Creating a Wardrobe of Wonder

Across nearly every medium Disney has touched, since the earliest days of animation, through innovations in live-action filmmaking and pioneering efforts in television, location-based entertainment and retail, and even gaming—one creative aspect of Disney has been seldom-documented, but is ever-present: that of costume design. And yet, in all the varied narrative media of Disney, costumes are as significant and memorable an element of building a character and telling a story as any other aspect, from script to sound and from performance to production design.

“Our job is often confused with diminutive stuff like shopping,” Oscar-nominated costume designer Deborah Nadoolman Landis says. “But if you talk to costume designers, they want to have an intellectual discussion. They want to make great movies, not necessarily great costumes. We design from the inside out, not the outside in. We bring characters to life.”

Costume designer Brianne Gillen agrees. “The costume offers a glimpse into the character’s personality, and often it’s on a subliminal level,” she says. “Because we all have an idea of what clothes convey, we immediately, and without even realizing, make a judgment about who a person is when we see them. A good costume designer helps the audience do this with a character. Costume design is hugely important for the story. Often, what a character is wearing tells the audience a lot about them before they even say a word of dialogue. You can tell a character’s socioeconomic status, sometimes their profession, the time of year, the city they live in—all by what they have on.”

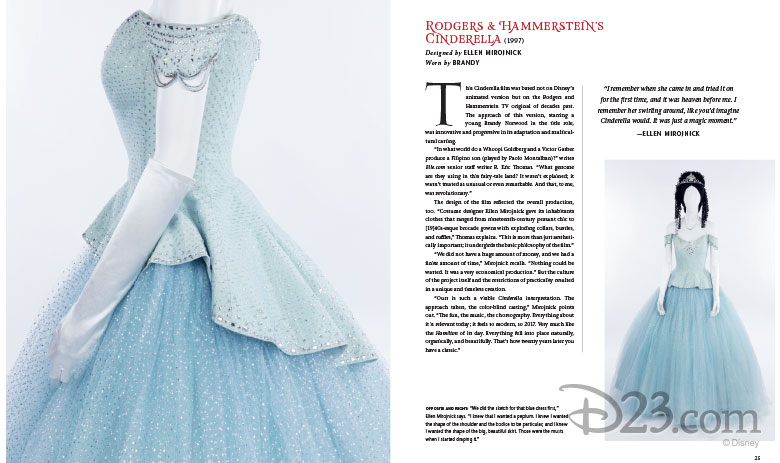

Ellen Mirojnick’s Design of Cinderella’s ball gown from Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella (1997), as worn by Brandy

Starring a young Brandy Norwood in the title role, this version of the Cinderella story was innovative and progressive in its adaptation and multicultural casting. The design of the film reflected the overall production, too. “Costume designer Ellen Mirojnick gave its inhabitants clothes that ranged from nineteenth-century peasant chic to [19]40s-esque brocade gowns with exploding collars, bustles, and ruffles,” writes Elle.com senior staff writer R. Eric Thomas. “This is more than just aesthetically important; it undergirds the basic philosophy of the film.”

“We did not have a huge amount of money, and we had a finite amount of time,” Mirojnick recalls. “We did the sketch for that blue dress first. I knew that I wanted a peplum. I knew I wanted the shape of the shoulder and the bodice to be particular, and I knew I wanted the shape of the big, beautiful skirt. Those were the musts when I started draping it. . . Nothing could be wasted. It was a very economical production.”

But the culture of the project itself and the restrictions of practicality resulted in a unique and timeless creation. “Ours is such a viable Cinderella interpretation. The approach taken, the color-blind casting,” Mirojnick points out. “The fun, the music, the choreography. Everything about it is relevant today; it feels so modern. . . . Very much like the Hamilton of its day. Everything fell into place naturally, organically, and beautifully. That’s how 20 years later you have a classic.”

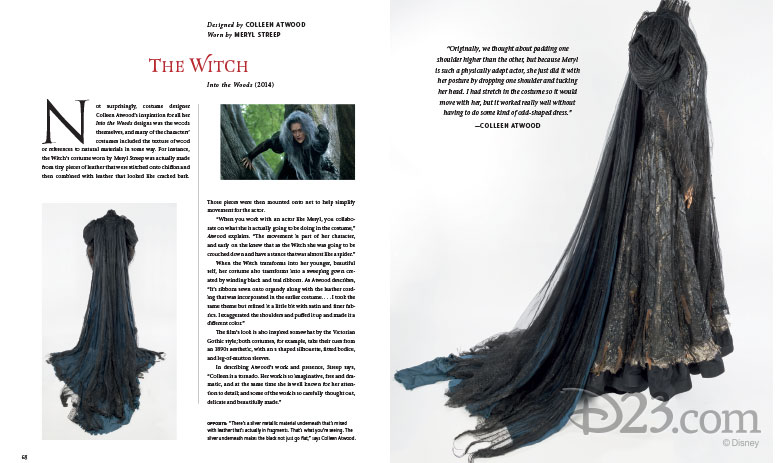

Colleen Atwood’s Design of the Witch from Into the Woods (2014), as worn by Meryl Streep

Not surprisingly, costume designer Colleen Atwood’s inspiration for all her Into the Woods designs was the woods themselves, and many of the characters’ costumes included the texture of wood or references to natural materials in some way. For instance, the Witch’s costume worn by Meryl Streep was actually made from tiny pieces of leather that were stitched onto chiffon and then combined with leather that looked like cracked bark. Those pieces were then mounted onto net to help simplify movement for the actor.

“When you work with an actor like Meryl, you collaborate on what she is actually going to be doing in the costume,” Atwood explains. “The movement is part of her character, and early on she knew that as the Witch she was going to be crouched down and have a stance that was almost like a spider. Originally, we thought about padding one shoulder higher than the other, but because Meryl is such a physically adept actor, she just did it with her posture by dropping one shoulder and tucking her head. I had stretch in the costume so it would move with her, but it worked really well without having to do some kind of odd-shaped dress.”

The film’s look is also inspired somewhat by the Victorian Gothic style; both costumes, for example, take their cues from an 1890s aesthetic, with an S-shaped silhouette, fitted bodice, and leg-of-mutton sleeves. In describing Atwood’s work and presence, Streep says, “Colleen is a tornado. Her work is so imaginative, free and dramatic, and at the same time she is well known for her attention to detail; and some of the work is so carefully thought out, delicate and beautifully made.”

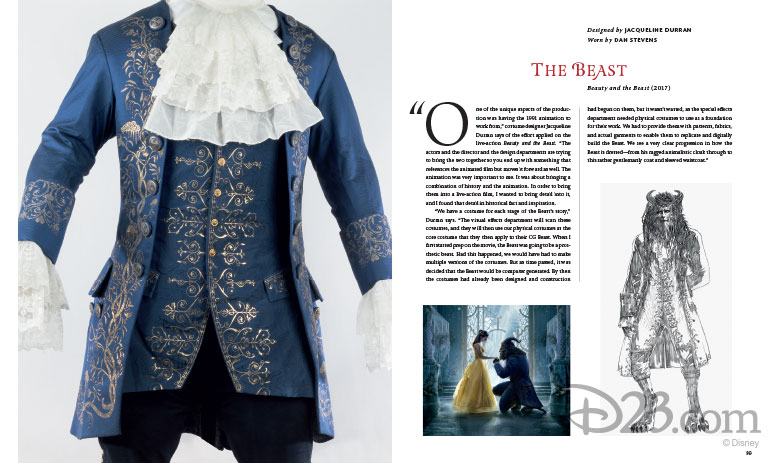

Jacqueline Durran’s Design of Beast from Beauty and the Beast (2017), as worn by Dan Stevens

One of the unique aspects of the production was having the 1991 animation to work from,” costume designer Jacqueline Durran says of the effort applied on the live-action Beauty and the Beast. “The actors and the director and the design departments are trying to bring the two together so you end up with something that references the animated film but moves it forward as well. The animation was very important to me. It was about bringing a combination of history and the animation. In order to bring them into a live-action film, I wanted to bring detail into it, and I found that detail in historical fact and inspiration.

“We have a costume for each stage of the Beast’s story,” Durran says. “The visual effects department will scan these costumes, and they will then use our physical costumes as the core costume that they then apply to their CG Beast. When I first started prep on the movie, the Beast was going to be a prosthetic beast. Had this happened, we would have had to make multiple versions of the costumes. But as time passed, it was decided that the Beast would be computer generated. By then the costumes had already been designed and construction had begun on them, but it wasn’t wasted, as the special effects department needed physical costumes to use as a foundation for their work. We had to provide them with patterns, fabrics, and actual garments to enable them to replicate and digitally build the Beast. We see a very clear progression in how the Beast is dressed—from his ragged animalistic cloak through to this rather gentlemanly coat and sleeved waistcoat.”

Sandy Powell’s Design of the Fairy Godmother from Cinderella (2015), as worn by Helena Bonham Carter

Helena Bonham Carter’s costumes turned out to be quite difficult to design, as there are the two sides to her character—and could be absolutely anything. Costume designer Sandy Powell ended up designing the costume for the beggar woman, who approaches Cinderella after her stepmother rips her mother’s gown, first. “I was opposed to doing the traditional beggar woman in a raggedy woolen cloak and hood,” she says, “and thought it would be far more interesting instead if she looked like the woods from which she appears.”

As for the Fairy Godmother, Powell wanted to fulfill every young girl’s dream and bring the treasured character to life in a luminous and magical way. To accomplish this, she created a white gown with silver wings made up of 131 yards of fabric, ten thousand crystals, and four hundred little LED lights, which were stitched throughout the material and lit up when she cast a spell.

“I kind of originally wasn’t going to put wings on because it hadn’t occurred to me that the Fairy Godmother would have wings,” Powell remembers. “I thought it just sort of a figure of speech—the ‘fairy’ Godmother. And [Bonham Carter] actually said to me during one of the fittings, ‘When was the last time you saw a fairy without wings?’ And I had to concede and give her wings—especially after she went to the director also and said, ‘I really want wings.’ We gave her the wings, and I think it was a good idea in the end.”