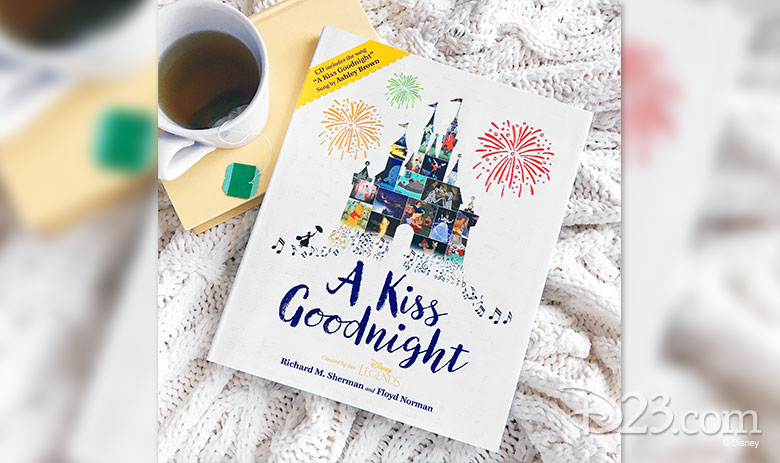

Excerpt #1— A Kiss Goodnight

By Disney Legend Richard M. Sherman and Illustrated by Disney Legend Floyd Norman

THE BIRTH OF A SONG

The question I have been asked most frequently throughout the six decades of my songwriting career is “What comes first, the words or the music?” The answer invariably is “Neither.” The mark of a good song is most definitely born from a third ingredient: the idea.

Ideas are formed from everyday life. Loss, love, doubt, regret, funny or sad situations, flashes of wit or wisdom—all can trigger song ideas. But many of the best song ideas are derived from the inspiration a good story can evoke. In the case of the Sherman brothers, many of our best songs were sparked by the characters and adventures we found in The Jungle Book, Tom Sawyer, Charlotte’s Web, Winnie the Pooh, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and, of course, Mary Poppins. However, each of those songs is part of a larger entity, a song score, created to help tell a particular story.

The independent or popular song is an orphan, derived from and related to nothing but itself. Songwriters are always on the alert for a good idea or a “hook” to inspire their music and lyrics. Sometimes a hook just drops into your lap. But sometimes that great idea can take half a century to emerge.

I vividly recall a lovely spring evening in 1963. At that time, my brother Robert and I were enjoying our third year as Walt Disney’s staff songwriters. My wife, Elizabeth, and I had spent the entire day taking in the fabulous sights, sounds, and experiences of Disneyland. We had lingered long after most of the day’s guests had departed when I noticed a lone figure slowly strolling down Main Street, looking in the storefront windows. That lone figure was Walt Disney.

I told my wife I wanted to let the boss know how much we loved our day at his park. Walt approached us with a smile, saying, “Hello, Richard. Shouldn’t you be on your way home by now?” I said, “Walt, we just had to thank you for the most wonderful time today. In fact, when the fireworks started and the music was playing and Tinker Bell flew across the sky, I was so overcome with happy emotions that I was crying.” Walt looked me straight in the eye and with a little smile said, “You know, I do that every time. . . . Now drive home carefully.” With a fond wink, Walt headed for his apartment above the fire station.

Over half a century later, I was asked to participate in the Diamond Jubilee, a project for Disneyland’s sixtieth anniversary. It was then I learned the little-known story about the park fireworks that have been enchanting millions of Disneyland guests for decades.

As a little boy in Marceline, Missouri, Walt rarely, if ever, had money for toys or amusements. But every Fourth of July, he’d burst with joy, because he could see free fireworks shows all over town. The brilliant colors and patterns of the explosions always triggered his fertile imagination and inspired his boundless creativity. Years later, when Walt and his Imagineers were completing Disneyland, he wanted to say thank you to all his guests when they left the park. His gratitude would come in the form of free fireworks (with the added touches of music and a flying Tinker Bell). He referred to this as “a kiss goodnight.”

Now, there’s an idea for a song! And what a hook! I immediately pictured that little boy who became the greatest entrepreneur of the twentieth century, that same great man who winked at me one night at Disneyland. I just had to write this song. I had to express how I imagined a young Walt was feeling as he watched magic dancing in the sky.

Walt Disney’s limitless ambition, his incredible storytelling talents, and, above all, his love for all mankind continue to inspire, entertain, and educate millions upon millions of people throughout the world. I’m certain his great legacy will live on throughout time. But I think it’s especially wonderful to remember that a poor little boy in Missouri, one century ago, dreamed big dreams. And when one of his greatest dreams, Disneyland, became a reality, he simply wished to thank all his guests for coming with “a kiss goodnight.”

THE STORY

Long ago, there was

a farm in Missouri . . .

where there were always chores to be done.

There was a six-year-old boy who

saw what others didn’t see.

He was a poor boy who waited for one

special evening every year, when his magical

dreams seemed to ignite the sky—in the

Fourth of July fireworks.

To him, it was the perfect kiss goodnight. . . .

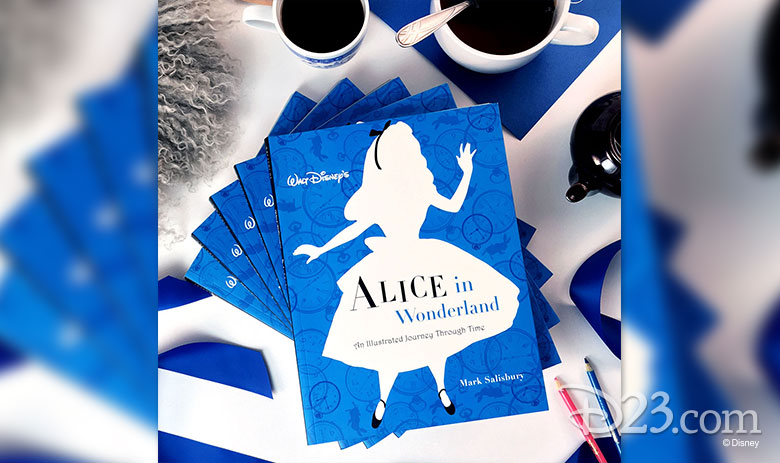

Excerpt #2— Walt Disney’s Alice in Wonderland: An Illustrated Journey Through Time

By Mark Salisbury and with a Foreword by Disney Legend Kathryn Beaumont, as told to Mindy Johnson, and an Introduction by James Bobin

START AT THE BEGINNING: THE ALICE COMEDIES

Walter Elias Disney, better known as Walt, was like so many children of his generation, and countless since. He was enchanted by Lewis Carroll’s book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass (two children’s classics now more commonly presented as one under the combined title of Alice in Wonderland).

“No story in English literature has intrigued me more,” Walt revealed later in life. “It fascinated me the first time I read it as a schoolboy, and as soon as I possibly could, after I started making animated cartoons, I acquired the film rights to it.” . . .

Born in Chicago in 1901, Walt lived in Kansas City, Missouri, from ages nine to fifteen.

A short time later, after a year working as a Red Cross ambulance driver in France following the end of World War I, he returned to the United States with aspirations of becoming an actor, artist, or cartoonist before eventually finding employment with Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio at Grays Advertising in Kansas City, where he drew ads for newspapers and movie theaters. It was here that Walt, now eighteen, met fellow artist Ubbe Iwwerks (later known as Ub Iwerks) with whom he would form, in 1920, a commercial arts business called Iwerks-Disney Studio. It was only open for a month, but it led Walt and Iwerks to join the Kansas City Film Ad Company, where they learned to animate, with the pair writing and directing ads.

Walt was hooked on what was then still a nascent medium. “The trick of making things move on film is what got me,” he recalled later.

In 1921, Walt set up shop in his father’s tiny garage and, with the help of his older brother Roy, began making experimental cartoons of his own. That fall, while still working at Film Ad, he started Kaycee Studios, producing a series of animated one-reelers, contemporary spins on traditional fairy tales. Included among them were Red Riding Hood and The Four Musicians of Bremen. The Kaycee venture lasted just a year before Walt decided to go into business as a producer of animated cartoon comedies and formed a new company, Laugh-O-gram Films, with a staff of ten, including Iwerks, who in November 1922 started as his chief animator.

Still, while only twenty years old, Walt animated, operated the camera, and continued the fairy-tales series with Jack and the Beanstalk, Goldie Locks and the Three Bears, and Puss in Boots. But Walt, not for the last time, began to overstretch himself, and Laugh-O-gram Films soon ran into financial trouble, particularly when a long-promised distribution deal failed to materialize. Walt moonlighted as a newsreel cameraman and baby photographer to keep the company afloat, but his efforts weren’t enough: Laugh-O-gram was quickly heading toward bankruptcy.

By then, however, Walt had had an idea for a new cartoon series. With the talented Iwerks by his side, Walt proposed a series of shorts that would combine live-action with animation. While the idea itself wasn’t new—animated characters interacting with the real world was familiar from Max and Dave Fleischer’s cartoon series Out of the Inkwell—Walt’s twist was that a real character would enter an animated world and intermingle with cartoon characters, specifically a girl called Alice, so named after Lewis Carroll’s singular creation.

Alice’s Cartoonland, as the test film was initially titled, would prove to be pivotal to not only Walt’s future as an animation producer, but also the medium in general. To find his Alice, Walt remembered a young girl who’d appeared in an advertisement playing at the local theater, “eating,” as he recalled, “this piece of Warneker’s Bread with a lot of jam on it.” With her blond ringlet curls and winning smile, the four-year-old Virginia Davis was deemed a miniature Mary Pickford. Walt approached her parents with an offer of 5 percent of the receipts for Davis to star in his short. Both sides signed the contract on April 13, 1923, with work beginning immediately despite the studio’s financial concerns.

Alice’s Wonderland, as the short would come to be known, ran for twelve and a half minutes, with the opening credits announcing produced by a Laugh-O-gram Process and scenario and direction by Walt Disney. The film began with Alice (played by Davis) arriving at the Laugh-O-gram Films animation studio. “I would like to watch you draw some funnies,” she tells Walt who asks her to be seated at his drawing desk where he has already sketched a doghouse on a sheet of paper. Suddenly, a cartoon cat runs out, having gotten into a fight with the doghouse’s canine occupant.

On a nearby drawing board, soon after, two cats dance to a feline band, while, at another drawing station, an animated cat and a dog engage in a boxing match, cheered on by Laugh-O-gram staffers Rudolph “Rudy” Ising, Hugh Harman, Iwerks, and two others. Retrospectively viewed as perhaps a sign of things to come, the studio’s real-life cat is shown harassed by a cartoon mouse that’s armed with a sword and has a pointy tail.

That night, at home, Alice dreams of an animated world that’s populated by cartoon characters. In her dream, she arrives in Cartoonland by train—its “over the mountains” journey presaging the train sequence in Dumbo—where she’s greeted by a cartoon welcoming committee, before riding an elephant in a parade through the city. . . .

Walt filmed Davis at Laugh-O-gram’s studio and in her own bedroom with her Aunt Louise playing her mother. For the Cartoonland sequences, Davis was photographed against a white backdrop onto which the cartoon characters were later added; Walt animated these scenes mostly by himself. The result was primitive but wonderfully effective: moviegoers saw Davis’s bubbly persona balanced by the crude but fun cartoon characters and simplistic animation.

In May 1923, several months before the film was completed, Walt fired off letters to all potential distributors, keen to secure a deal for Alice which, he hoped, would turn around the company’s fortunes. “We have just discovered something new and clever in animated cartoons,” he wrote to New York-based film distributor Margaret J. Winkler. . . .

Winkler, or Peggy as she was better known, was the first woman to produce and distribute animation in the United States and was the distributor of Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat cartoons and the Fleischer brothers’ Out of the Inkwell series; her releasing Alice would, Walt reasoned, guarantee its success. On receiving Walt’s letter, Winkler dispatched a swift, enthusiastic reply, writing, “If it is what you say, I shall be interested in contracting for a series of them.” Walt took heart in Winkler’s interest and, despite his and the company’s worsening financial position—he’d been kicked out of his apartment and had taken to sleeping at the studio—pushed on to complete Alice’s Wonderland.

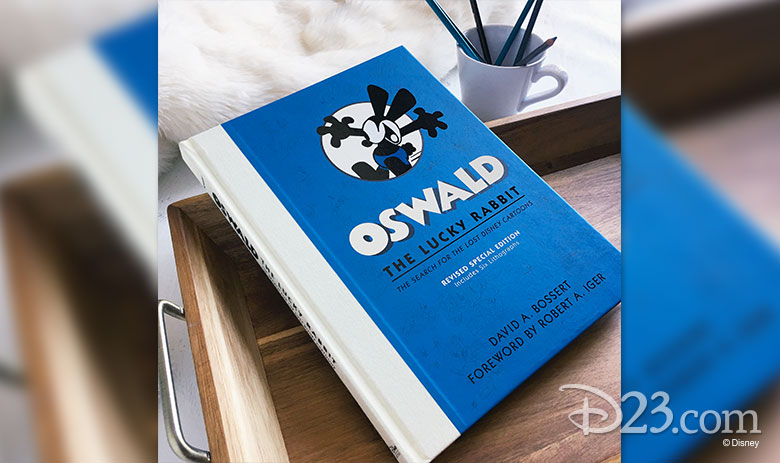

Excerpt #3— Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons, Revised Special Edition

By David A. Bossert and with Contributions by David Gerstein, a Foreword by Bob Iger, and an Introduction by J.B. Kaufman

THE ORIGINS OF OSWALD THE LUCKY RABBIT

. . . During the Alice Comedies production period—from 1923 through 1927—the Disney brothers produced fifty-six Alice short subjects, as their studio continually expanded in size with new staffers being brought aboard. Rollin “Ham” Hamilton was the first animator that Walt hired, on February 11, 1924, to work on the Alice Comedies. By June of that year, Walt was convincing Ub Iwerks to leave his job in Kansas City—where Iwerks was working at the Kansas City Film Ad Company—and join him in Hollywood. Walt had first met Ub in 1919 when they both worked at Pesmen-Rubin, an advertising agency. Iwerks ultimately agreed to join Walt as an animator. Once Ub—an artist of legendary speed and skill—arrived on staff in July 1924, there was a noticeable uptick in quality in the Alice Comedies, with more, and stronger, animation and less live action (but with technical improvements in how the two were combined).

The Disney brothers made a down payment on a property for a new studio building on Hyperion Avenue to accommodate both their continued expansion and the increasing pressure to strengthen the quality and pace of production. By 1926, the studio had about ten employees, which included support staff. (The Hyperion Disney lot, over time, would grow into a formidable studio complex employing hundreds of artists and technicians.)

But by 1927, the popularity of the Alice Comedies began to wane. Walt himself was beginning to feel that the series was in a creative rut and losing its novelty; it had run its course. The live-action Alice was becoming less important to the story lines, and the series’ lead animated character, Julius the cat, had evolved into a derivative of the famous Felix; Walt had resisted the urge to imitate Felix, but Mintz and Winkler had insisted. The pressure to produce a short every two to two-and-half weeks was taking its toll on Walt and the studio staff.

At the same time, Mintz was already looking for an all-new animation series featuring a new character without a live-action component and was in discussions with Universal to supply it. However, the executives at Universal felt that there were too many cat characters in the marketplace; Felix the Cat, Krazy Kat, and of course Julius in the Alice Comedies contributed to the reasons why Universal wanted something new. Mintz, true to form, pushed Walt to deliver “what they wanted.”

Walt and his top animator, Iwerks, created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in early 1927 in response. Mintz went to Hollywood to sign a contract with Universal to provide twenty-six cartoons featuring the new character. In turn, Walt signed a contract on March 19, 1927, with the Winkler Film Corporation to complete production on “twenty-six (26) one (1) reel motion pictures of animated cartoons, featuring a rabbit character . . .”

. . . Mintz, upon returning to New York, wired Walt on March 28: Arrived safely and find everyone enthusiastic about Oswald . . . Universal wants Oswald sketches . . . I requested soon as possible. Walt sent over the drawings and sketches of Oswald, but the enthusiasm was short-lived; for when Walt sent over the first Oswald cartoon, Poor Papa, a little over two weeks later, it received a disappointing response from both Universal and Mintz.

On April 15, 1927, Mintz sent Walt a telegram at the 2719 Hyperion Avenue studio: Oswald arrived today and am disappointed. . . Universal and Mintz felt that there were too many ancillary characters—specifically, a swarm of babies and storks—causing Oswald to get lost in the action. They also thought that Oswald was too elderly and “sloppy and fat,” and they wanted him to be “young and snappy looking.” Mintz even suggested that the character have a monocle, which later Walt declined to do.

Mintz followed his telegram with a letter, which he accompanied with a copy of the letter he had received from Universal, giving a point-by-point critique of the Poor Papa short. The letter from Hal Hodes, sales director of the Short Product & Complete Service Departments, began by stating that, “the committee is keenly disappointed in [Poor Papa].” Hodes went on to describe the “faults we found with it”:

(1) Approximately 100 feet of the opening is jerky in action due to poor animation.

(2) There is entirely too much repetition of action. Scenes are dragged out to such an extent that the cartoon is materially slowed down.

(3) The Oswald shown in this picture is far from being a funny character. He has no outstanding trait. Nothing would eventually become characteristic insofar as Oswald is concerned.

(4) The picture is merely a succession of unrelated gags, there being not even a thread of a story throughout its length.

Walt took the criticism in a professional manner, at least in his response to Mintz. But he still must have been frustrated and disappointed. Responding on April 21, Walt sent Mintz a letter acknowledging the criticism and discussing each point made in Hodes’s assessment of Poor Papa. “First of all, I want to say that the spirit of criticism shown by Mr. Hodes is constructive and very much appreciated, and that I hope it will continue.” Putting as good a face on the situation as he could, Walt continued, “I am sorry that the first ‘OSWALD’ was such a keen disappointment to everyone, but I am not exactly surprised, as I was disappointed in it myself. This was not thru [sic] a result of any indifference or slackness on my part, but seemingly a wrong slant on it.”

He then went on to discuss each point laid out in Hodes’s letter and offer up solutions and corrective action going forward. Disney did push back on the first point—regarding the jerkiness of the animation—by suggesting that the Universal committee may not have looked at the film at the correct speed. Regardless, Poor Papa was shelved for the time being and not released until 1928.

Walt went on at length about Hodes’s letter in a four-page response to Mintz, vowing “to make Oswald peculiarly and typically Oswald, and not merely a rabbit character animated and shown in the same light as the commonly known cat characters.” Over the shorts that followed Poor Papa, Disney and his animators would continue to make refinements and adjustments to Oswald’s design. And there is a vast difference in Oswald’s look from the roly-poly image on the standard title card to how Oswald looks in the later shorts at the end of the Disney production year.

In response to the Universal claim that Oswald “has no outstanding trait,” Walt said, “It was our idea tho [sic], to make characteristics, his [entire] style and manner of doing things, rather than to give him merely a specific trait or habit.” Walt wanted to give Oswald a distinctive personality all his own, which transcended any superficial habit or visual tic: one that would be recognizable by the public as purely Oswald. Over several cartoons, this persona—an emotive, fast-moving wise guy, alternately ebullient and grouchy—would come into focus.

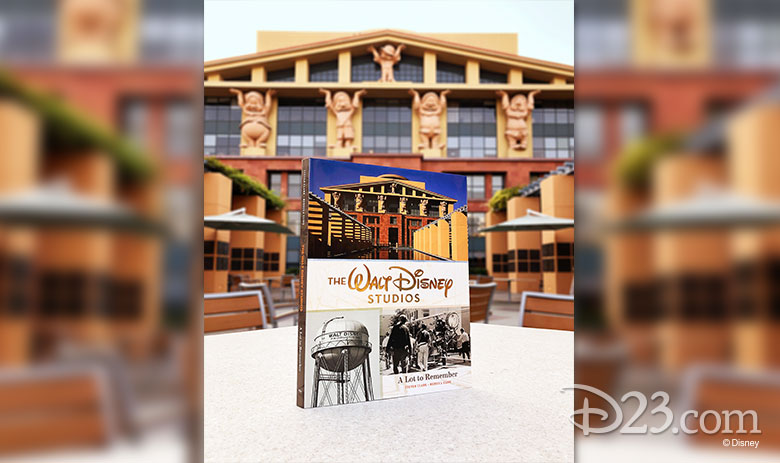

Excerpt #4— The Walt Disney Studios: A Lot to Remember

By Rebecca Cline and Steven B. Clark

THE FLEDGLING STUDIOS

Walt and Roy scouted the surrounding neighborhoods, and on July 6, 1925, they finally placed a $400 deposit on a small parcel of land at 2719 Hyperion Avenue in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles. Construction of the new onestory studio began shortly afterwards in July of 1925 and was completed the following February. Walt and Roy claimed the two partitioned offices, but the bulk of the space was left open for the animation, background, and inking and painting departments.

Over the next three years, the Disney brothers and their team of artists produced fifty-six Alice Comedies at the Hyperion studio before signing another contract with Winkler in 1927 for a cartoon series with a brand-new star: Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. He was charming, mischievous, and soon to be immensely popular. Walt and company produced twenty-six Oswald cartoons in the first year, and Walt hoped to secure additional funding from their distributor to improve the animation quality as he headed east to adjust the contract Disney had with Winkler and her new husband and partner, Charles Mintz.

But upon arriving in New York, he discovered that Winkler and Mintz had their own plans for Oswald—ones that didn’t include Walt and Roy. The distributor, who owned the rights to the character, planned to drastically reduce the Disney brothers’ management role and make the Oswald cartoons in their own studios at what they argued would be a substantially lower cost. And that wasn’t the worst of it: Mintz had already hired most of Walt’s staff out from under him.

Never one to dwell on setbacks, Walt spent the long train ride heading back west after losing Oswald brainstorming and thinking of a new character. He met with Roy and a few remaining loyal staff members upon his return to map out a plan for the future. With the help of his chief animator and friend, Ub Iwerks, Walt went to work creating what would soon become the world’s most famous mouse. Unfortunately, the new character also boasted just about the world’s worst name—Mortimer—before Walt’s wife, Lillian, persuaded him to change it to Mickey. The new name stuck, thankfully, though Walt would go on to use the name Mortimer as one of Mickey Mouse’s rivals.

Iwerks animated two silent Mickey Mouse cartoons, Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho, but Walt was unable to find a distributor. Though only a few years removed from the success of the Alice Comedies and Oswald shorts, much had changed in the entertainment world. The Jazz Singer, the first motion picture with sound, had premiered in 1927, entrancing theater audiences everywhere. And so it was to be a third cartoon, Steamboat Willie, the first animated film to feature fully synchronized sound, that would end up serving as Mickey Mouse’s “official” debut. Steamboat Willie opened on November 18, 1928, at the Colony Theater in New York. The plucky and playful star of the movie was suddenly an overnight sensation.

Want more? Be sure to check back here for additional excerpts from this amazing collection!