Tchaikovsky’s 1892 ballet The Nutcracker has become a holiday favorite. To celebrate this enduring classic and seasonal hallmark, Disney historian and author Alexander Rannie takes a fond look back at the stunningly beautiful Nutcracker Suite sequence from Fantasia.

1. Americans had never seen the complete Nutcracker ballet when Fantasia premiered in 1940

It wouldn’t seem like Christmas without the melodic strains of Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s 1892 ballet The Nutcracker floating up from the orchestra pit, or wafting forth from the TV screen, or gliding along the grocery store aisle. But when Walt Disney’s animated interpretation of The Nutcracker Suite made its debut in 1940 as one of Fantasia’s eight musical episodes, there had yet to be a complete production of The Nutcracker in the United States. It wasn’t until Christmas Eve of 1944 that the San Francisco Ballet produced the work in its entirety. And in 1954—the same year as the first full-length recording of The Nutcracker was released on vinyl—famed choreographer George Balanchine mounted his version for The New York City Ballet. Balanchine wisely included several dozen children in the cast, knowing that their parents, extended family, and friends, would all purchase tickets. the New York City Ballet production has proved such a success that it now averages almost 50 performances every year!

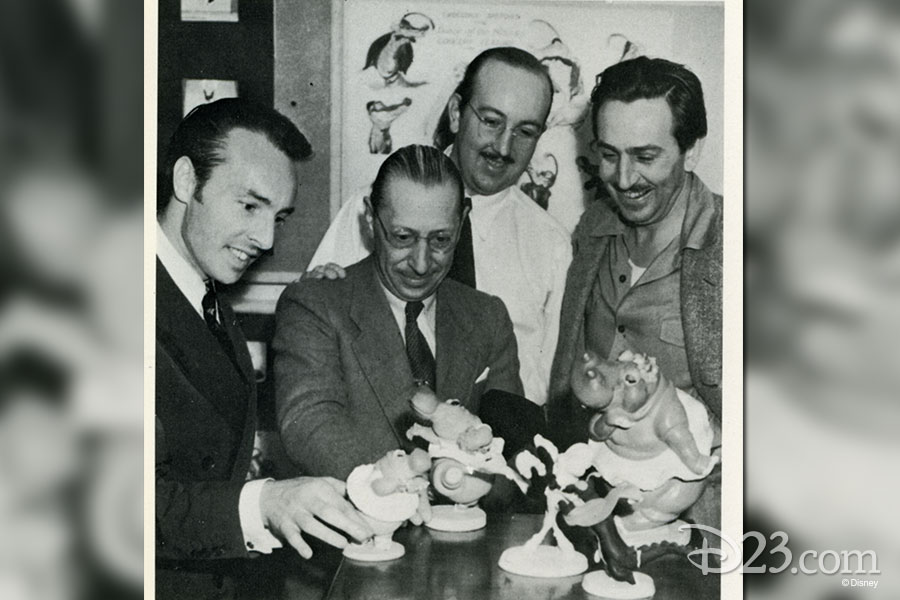

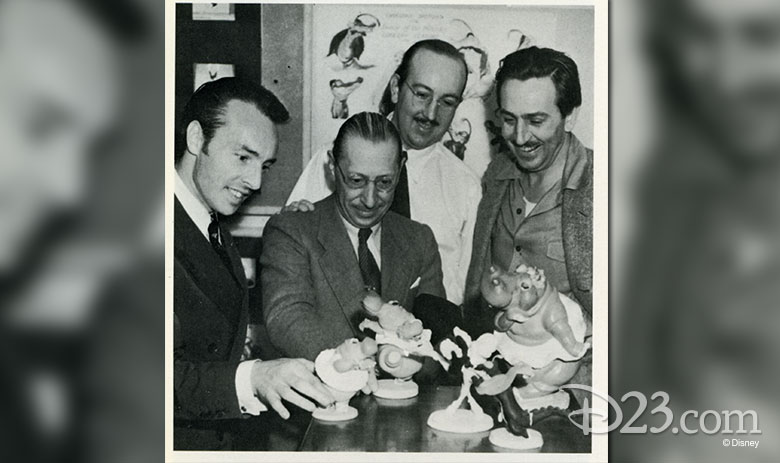

George Balanchine visited the Disney Studios in 1939, along with composer Igor Stravinsky (whose Rite of Spring makes a memorable appearance in Fantasia). Both were quite taken with the hippos, alligators, ostriches, and elephants in Fantasia’s send-up of classical ballet in Dance of the Hours. Stravinsky and Balanchine collaborated on numerous ballets, including one based on the music of Tchaikovsky, Le baiser de la fée. When he was 11, Stravinsky briefly saw his musical hero in the foyer of Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre. “A glimpse of Tchaikovsky,” Stravinsky said, “was to become one of my most treasured memories.”

2. Walt’s interpretation of The Nutcracker Suite has its origins in the Silly Symphonies

It’s often said that Fantasia is the ultimate Silly Symphony, with music, rather than story or character, as its driving force. But of all the segments in Fantasia, The Nutcracker Suite, with its frolicking flowers and fairies, harkens back most strongly to the earliest Silly Symphonies. Springtime (1929) was touted by the Studio as, “The first animated picture in which flowers were used to interpret a ballet.” (It was quickly followed by Summer, Autumn, and Winter in 1930). Flowers and Trees (1932) was the first commercially released three-strip Technicolor cartoon and featured a chorus of dancing daisies. But Walt was always thinking bigger, and the idea of a grander floral ballet was discussed in story meetings as early as May of 1935. The title of this opus was to be Ballet des Fleurs, and, though it was never made, many of its elements were eventually incorporated into the version of The Nutcracker Suite that we know today.

3. Women played a major role in the creation of The Nutcracker Suite

Women have always played a large, if not readily visible, part in the creation of Walt Disney’s animated cartoons. In The Nutcracker Suite, more than any other segment, talented women were called upon to create some of Fantasia’s most beautiful moments. Story artists Sylvia Moberly-Holland, Bianca Majolie, and Ethel Kulsar transformed the blossoms and weeds they found on the hillsides around the Hyperion Studio into the floral soloists, corps de ballet, Cossacks, and orchid girls that populate Tchaikovsky’s Suite. Their use of pastels in storyboard drawings prompted the women in the Ink & Paint department to develop new ways of painting cels. (More on this in a moment!) In order to create the sinuous and mysterious movements of the Arabian fish, Joyce Coles of the Belcher School of Dancing was brought on board to choreograph an appropriate dance. Cole’s cohort and live-action reference model for Snow White, Marjorie Belcher (later known as Marge Champion) provided reference for the endless pirouettes of the prima ballerina in the Blossom Ballet. And Assistant Music Cutter Louisa Field made sure that conductor Leopold Stokowski’s recordings with The Philadelphia Orchestra perfectly matched the movement of the onscreen animation.

4. New Ink & Paint techniques were developed to bring The Nutcracker Suite to the screen

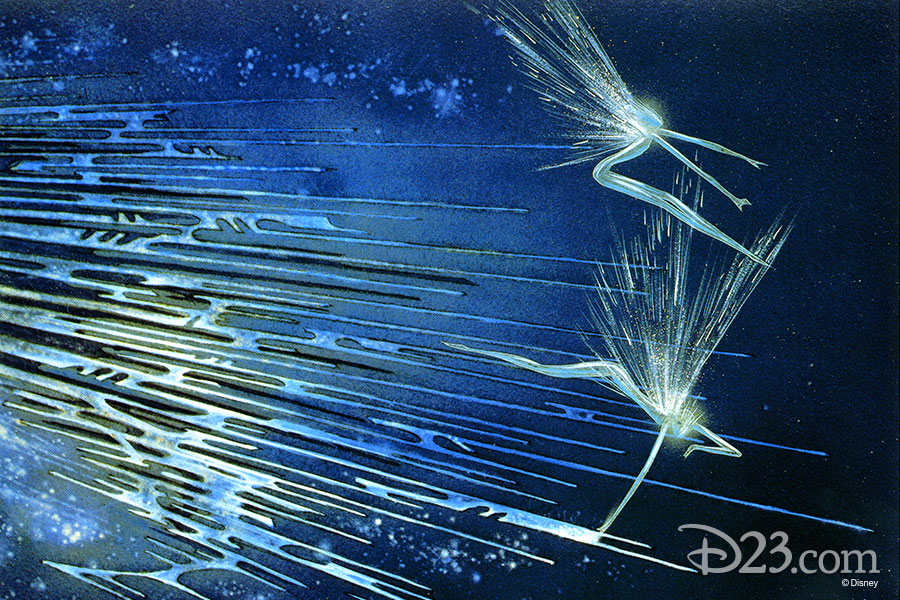

Walt was so impressed by the look and mood of the story sketches for The Nutcracker Suite that he asked his staff to find ways to avoid hard ink outlines and more closely mimic the pastel and painterly look of the inspirational artwork. For example, the windblown seeds in the milkweed ballet in “Waltz of the Flowers” required delicate inking, drybrush work (done with a brush whose bristles are dry, but can still hold paint), and airbrushing (similar to the effect of spray paint, and which required creating a mask (for each individual cel!) to keep certain areas free of paint). Other painting techniques employed in The Nutcracker Suite involved stippling and the use of transparent paint. It could take hours to complete a single cel, but the visually stunning end result made it all worthwhile. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston wrote of the exotic lead Arabian fish, “Never has an object on celluloid looked so diaphanous and delicate.”

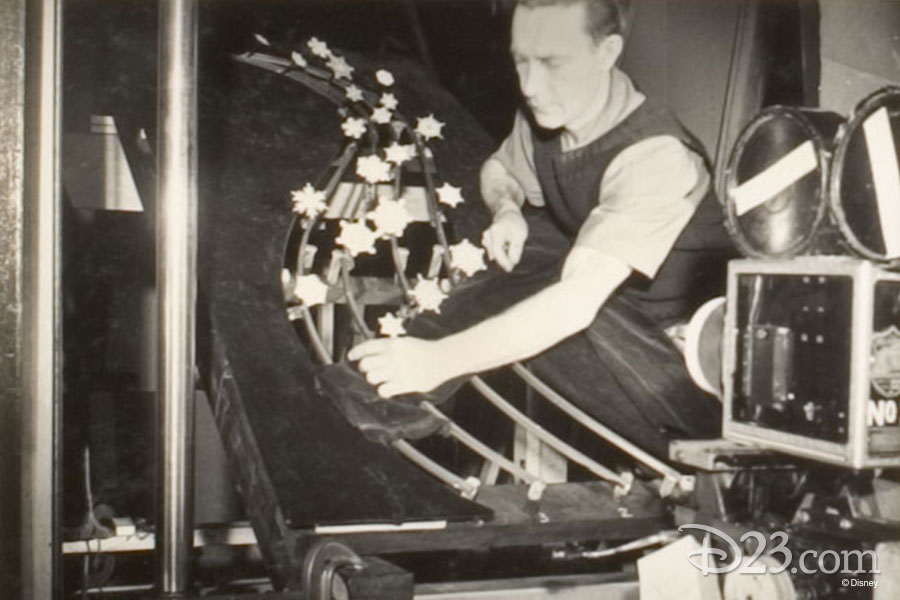

5. The Nutcracker Suite contains stop motion animation

Animation at the Studio during Walt’s lifetime was almost exclusively hand drawn, so it’s interesting to note that The Nutcracker Suite contains animation created using stop motion, i.e., animation created by physically manipulating an object in front of the camera. In the case of The Nutcracker Suite, Walt’s animators found themselves flummoxed at how best to create the Snowflake Fairies at the end of the “Waltz of the Flowers.” Hand drawing elaborate snowflakes would not only take an enormous amount of time, but they would inevitably wobble and flop about, unable to maintain the rigid structure of frozen water.

In his book Herman Schultheis and the Secrets of Walt Disney’s Movie Magic, Academy Award®-winning animator and historian John Canemaker reveals the solution. “To create this scene, Leonard Pickley, an inventive fellow in the Special Effects Department, started by suggesting that the Ink and Paint Department trace scientific diagrams of real snowflakes onto a material slightly heavier that regular cels and paint them in translucent white. Once cut out, each of the dozen or so snowflakes was secured atop revolving spools attached to small steel rails, like those used for Lionel toy trains. Black velvet covered the mechanics of the setup, and the three-dimensional snowflake models were hand-animated as the camera recorded the frame-by-frame progress down the hidden tracks.” Additional hand drawn animation of the fairies was added later. “The result,” Canemaker writes, “is a dozen scenes, each timed to the music at a progressively faster pace, that bring a snowstorm of enchanting creatures to the screen in a luminous climax to the ‘Nutcracker Suite,’ one of Disney’s most beautiful film masterpieces.”

To discover more about the Inking and Painting process, keep an eye out for author and historian Mindy Johnson’s upcoming book, Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, available from Disney Editions in 2017.