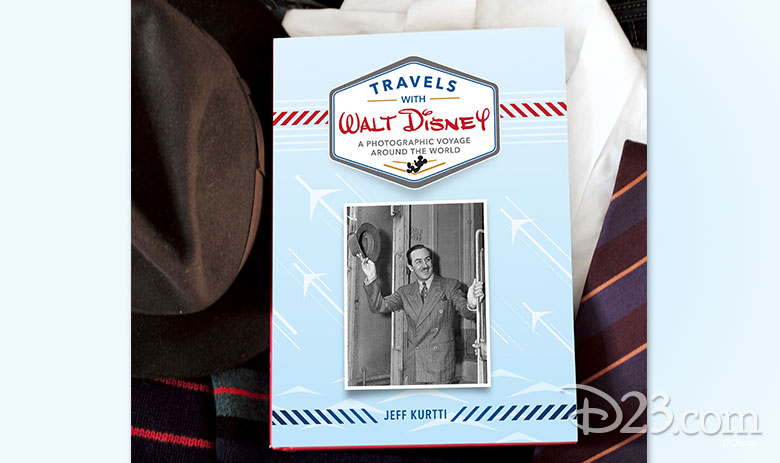

Excerpt #10—Travels with Walt Disney: A Photographic Voyage Around the World

By Jeff Kurtti

“I had a helluva breakdown . . . I got to a point that I couldn’t talk on the telephone. I’d begin to cry.”

—Walt Disney

THE GYPSY JAUNT

In October 1931, on doctor’s orders, Walt and Lilly Disney set out for their first vacation together so that Walt could relax and recuperate from the stresses of running an ever-growing studio operation.

Lilly nicknamed their trip “The Gypsy Jaunt.” She said, “We went first to St. Louis, where he wanted to take a steamboat down the Mississippi. Well, we couldn’t find one, so we had to take the train to Key West [Florida].”

From Key West, the Disneys hopped on another mode of transport that took the pair to Havana, Cuba!

ON THE HIGH SEAS

The notion of “leisure cruising” actually dates back to 1822, and the first ship built solely for “luxury passenger” traffic was completed in 1900.

Walt Disney’s experience as a passenger on oceangoing vessels began by serendipity, but he enjoyed the experience so much that for both work and play, he became a lifelong cruiser.

He wasn’t an elitist about it, though. In fact, Walt reportedly made every effort to escape the luxuries and attentions that were usually lavished on him by well-meaning crew and other passengers. He might have been traveling first class, but his tastes tended toward less formal activities and ostentatious fare than those of the usual luxury passenger. What Walt discovered on the high seas, it seems, was that it was one of the few places he could actually “unwind.”

“I’m not an ulcer type—though maybe I give them,” he chuckled. “But I do find it hard to relax while I am anywhere near my work, which I love. For the first time in years, because I’m on a ship, I get up at nine or ten in the morning. At home I never rise later than 6:30 a.m.”

THE GYPSIES AT SEA

“He was conscious that he was undergoing a breakdown, even though I wasn’t. He was having trouble concentrating on his work and remembering things. And so we decided to take off on a trip.”

—Lillian Disney

“We went to Havana, Cuba, where we stayed at the Nacional Hotel,” Lilly said. “We went out in the country, and it was stimulating to see different things. Then we took a boat trip back through the [Panama] Canal, and that was the best part of the whole trip. It was a good rest for Walt.”

The Disneys departed on that “boat trip” from Havana on November 3, 1931, aboard the luxury cruise ship the SS California, and arrived at the Port of Los Angeles on November 14.

ALOHA AND MAHALO, WALT DISNEY

The lure of the Hawai’ian Islands turned Walt and Lilly into lifetime cruisers.

“The 1930s were the heyday of Waikiki’s appeal,” states the fascinating website HawaiiHistory.org. “A beach boy culture grew up to service visitors and introduce them to the laid-back island lifestyle.” Hollywood movies, according to the site, “featured hula dancers and island settings, and the radio program Hawai’i Calls beamed Hawai’ian music to a national audience every week. Hawai’i became synonymous with an exotic sensuality.”

Walt and Lilly made their first trip to Hawai’i in 1934, sailing on the Matson liner Lurline from Los Angeles on August 10. Their first port was San Francisco the next day, and they arrived in Honolulu the morning of Thursday, August 16.

“Walt’s arrival in the islands was big news, rating a headline at the top of the [Honolulu] Advertiser’s August 17 front page, accompanied by photos of both Walt and Lilly,” reports Disney scholar and biographer Michael Barrier.

The Advertiser reported that “He had no sooner set foot ashore than he was besieged with invitations to go here, go there; to meet this one and do that for someone else.”

Walt was coy in reply, saying, “I don’t want to do anything except to lie on the beach in the sun and wiggle my toes in the sand.”

The Disneys departed Honolulu on Saturday, August 25, 1934.

ENGLAND ABOARD THE NORMANDIE, 1935

On June 12, 1935, Walt and Lilly (along with his brother Roy and his wife, Edna) arrived in Plymouth, England, after a voyage on board the French liner Normandie, which had departed New York on June 7. That voyage was the first crossing for the Normandie from the United States to England, having arrived in New York Harbor June 3. The Normandie was a record-setter: it was the first liner that was more than a thousand feet long, and faster than any other liner of its day—the crossing from Plymouth to New York had taken only 4 days, 11 hours, and 42 minutes.

From England, the Disneys journeyed to Scotland, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. A definitive account of this remarkable trip can be found in Didier Ghez’s book, Disney’s Grand Tour.

HEADING HOME, 1935

Six weeks later, on July 24, 1935, the Disneys headed for home from Naples, Italy, this time on board the elegant Italian liner Rex, arriving in New York City on August 1. Walt’s first European tour had certainly influenced him enormously. He told a reporter, “When you think about it, it is a little surprising to think that Mickey has become such a personage. They seem to know him just as well in Paris, London, Rome, and Berlin as they do in Hollywood and New York.”

Their tour finally ended at the Santa Fe Railroad Station in Pasadena, California, on Monday, August 5. . . .

“EL GRUPO” AFLOAT

In 1941 Walt was offered an unusual opportunity by the U.S. State Department to travel with artists and other talent from his studio and gather material to make animated cartoons about South American culture so United States citizens would have a better appreciation of their neighbors south of the border.

A studio press release stated that this entourage would research concepts and projects that would “utilize properly, in the medium of animation, some of the vast wealth of South American literature, music[,] and customs.” This Latin American adventure resulted in two “package features” (Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros) and the short cartoons Pluto and the Armadillo (1943), The Pelican and the Snipe (1944), and Blame It on the Samba (originally a segment of 1948’s full-length Melody Time and reissued as a stand-alone short in 1955).

Walt handpicked his traveling companions, who became known as “El Grupo.” Although El Grupo’s flight to South America was well-documented, the return portion of their visit is less well-known: “I was so worn out by the time we reached Chile that the boat trip home was the only way I could get any rest,” claimed Walt about the seventeen-day sea voyage home on the Grace Line’s Santa Clara.

“I was asked by the government to go to South America. . . . I went down with a staff to see if I couldn’t make some films about the ‘ABC’ countries down there . . . Argentine, Brazil, and Chile. And they first wanted me to go on a handshaking goodwill tour, and I said, ‘I don’t go for that—I’m not a good handshaker.’ . . . Then they came back and said, ‘Will you go down and make some films about these countries?’ I said, ‘Well, that’s—that’s my business. I can do that.’”

—Walt Disney, in an interview with Flether Markle, 1963

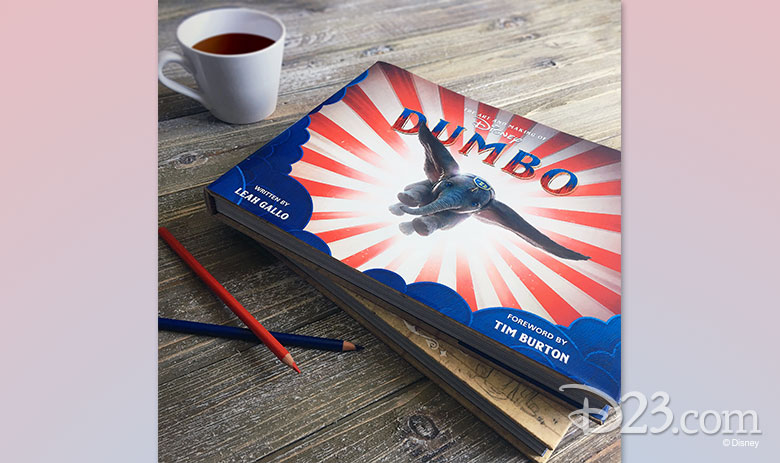

Excerpt #11—The Art and Making of Dumbo

By Leah Gallo and with a Foreword by Tim Burton

FIRST FLIGHT

Dumbo is one of The Walt Disney Studios’ most lauded animated features, collecting rave reviews when it was first released in 1941 and praise from animators in the field ever since. It’s been rereleased in theaters four times. It was one of the first Disney films ever to be released on VHS (soon followed by laser disc, then DVD, Blu-ray, and now digital download). With each release, whether in the theater or via rental or purchase, people willingly opened their hearts to watch the fantasy of a baby elephant that could fly.

Considering all of its eventual fame, Dumbo started its life rather innocuously in 1939—as a planned novelty item called a Roll-A-Book. It was a box with a window that displayed the story, and readers scrolled vertically through it by turning little knobs. Co-authorship credit is given to both Helen Aberson and Harold Pearl, a couple married just long enough to jointly author the book, titled Dumbo the Flying Elephant. Still, there are many mysteries surrounding it, such as the historical ambiguity as to whether a version of the Dumbo Roll-A-Book was ever officially published. If it was, very few copies were made, and none exist nowadays in any collections, including the historical collections of The Walt Disney Company. The search for one has become a mythical journey for collectors. Disney company historians and archivists, stumped at never having located one, are always on the lookout for this “holy grail” find.

The Dumbo story and concept first made its way to the Disney studios in 1939, when Herman “Kay” Kaymen (who entered into an agreement in 1932 with the studio to become the sole product licensing representative for Disney) showed John Clarke Rose, a Story Department manager at the studio, Dumbo the Flying Elephant as a demonstration of the new literary invention. “And there it was, a beautiful story with a beginning, a middle, and an end,” reminisced Rose in an interview with animator and director Milton Gray in 1978. “I probably told Kay that the Roll-A-Book per se was beyond my province, but that I damned well was going to propose [the story] to Walt.”

Walt Disney bought the story rights, which included an agreement to publish at least a thousand copies of a regular Dumbo the Flying Elephant book. The Disney-released book was published by Whitman Publishing Company in 1941, with some changes from the original story, utilizing the text as revised by Aberson. In the Roll-A-Book galleys, the preliminary text version meant for proofreading, (which do still exist—and are held at Syracuse University’s Bird Library) Dumbo is not a baby, but a tiny elephant with large, pink ears. He is ostracized at the circus for tripping, falling, and generally ruining an elephant act because of his clumsiness. However, the story does not include the disastrous scene of a tumbling elephant pyramid, nor does this Dumbo become a clown. His friend is a robin instead of a mouse, and an owl instead of a flock of crows teaches him to fly using his ears.

The 1941 Disney book with Aberson’s text revisions is a compromise between the original Aberson and Pearl story and the eventual film. Dumbo is now a baby elephant, and the story follows his difficult time in the circus, similar to the film. However, the robin and the owl characters remain. Approximately 1,430 copies were sold, which fulfilled Disney’s responsibilities to Aberson and Pearl and accordingly wrapped up the initial partnership on the little elephant that was to become a huge success.

The fact that Dumbo turned into any theatrical release at all is a bit of a miracle. In 1937, Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs became the first full-length animated feature film to ever be released, as well as a smashing success. Snow White had been a big investment for Walt and Roy O. Disney—both in faith and money. It cost the studio about $1.5 million to create, which was roughly as much revenue as the studio was making in a year at that time. It was an unheard-of amount for animation in the 1930s. But that faith was justified: audiences loved it, and the artists at the Disney studios were able to continue their great feature animation experiment. . . .

Dumbo‘s jump from a thirty-minute cartoon into a full-fledged feature occurred in early 1940. Joe Grant headed the Character Model Department, which was responsible for creating and refining the concept for a film’s characters and producing character reference. He had also become a source for project research and development. He and his friend in the department, Dick Huemer, who was a longtime animator and director, had supervised the story direction on Fantasia. They began to put together a treatment for Dumbo.

“I didn’t work on it at first,” remarked Huemer in the late 1970s, reflecting upon the time that Dumbo was in development and it was intended to be a short film. “Neither did Joe Grant. Then it was put aside for some reason. Walt wasn’t satisfied with it. Joe Grant and I decided we would do something. You could do things like that in those days. You could make up things and try to goose Walt along.” This “goosing” occurred by distributing the treatment to Walt chapter by chapter, in the hopes that such suspense would inspire enthusiasm and excitement. They would even dramatize their cliff-hangers, Huemer disclosed, by writing things on the page such as, “Read no further unless you are of strong character and can take it, because what

We’re going to tell you, you won’t believe—see you tomorrow!” . . .

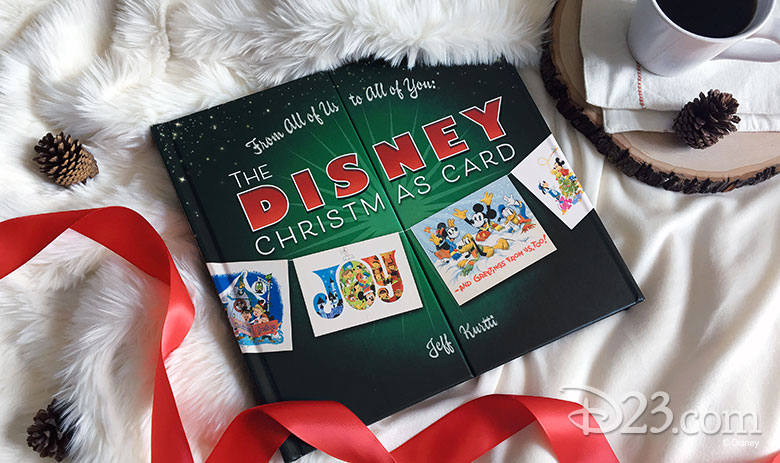

Excerpt #12—From All of Us to All of You: The Disney Christmas Card

By Jeff Kurtti

THE 1940s

Both the releases of the ambitious and expensive Pinocchio and Fantasia in 1940 proved financially disappointing, in large part because the war in Europe had cut off vital markets overseas. A contentious and disruptive animators’ strike in the spring of 1941 divided the studio and wounded Walt in a deeply personal way that ever after tempered his relationships with his staff. In the interest of escaping that conflict and promoting relations closer to home, in August 1941, Walt and a group of his artists went on a U.S. State Department–sponsored goodwill trip to South America.

Dumbo was released that October, and was a smash success. But just a few weeks later, the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. The very next morning—December 8, 1941—the U.S. Army moved onto the Disney studio lot.

Although work was finished on Bambi, which was released in August of 1942, the primary business of Disney became the war: military insignia, training films, and morale-boosting propaganda. It’s no surprise that this wasn’t a very profitable business, and as the Disney bank accounts dwindled, Walt and his brother Roy began to feel a little panicked.

A 1944 reissue of Snow White provided an enormous financial boost, and began a decades-long tradition of classic film theatrical rereleases to greet new generations about every seven years.

After the war, Walt was at a crossroads. The studio was not prepared to release another expensive and risky animated feature, but ultimately, he decided not to close down or cease production entirely. Walt took the lessons of wartime work and evaluated his assets and liabilities. If animation was to continue as a primary effort, Walt knew that the Disney studio would need to reclaim the crown; but efficiencies learned during the war would be incorporated.

Waste was trimmed; unprofitable, risky, or labor-intensive ventures were shelved or scrapped. A new Disney emerged from the 1940s, with a seemingly contradictory combination of nostalgia, innovation, versatility, and focus that would continue to represent Disney for decades to come.

THE 1950s

Walt Disney and his studio had survived the war years, and Walt continued to move an ever-varied slate of projects forward in his expansion of the definition of “Disney.” The year 1950, for instance, saw the release of Treasure Island, Disney’s first fully live-action feature.

That year also marked Disney’s debut in the new medium of television, with One Hour in Wonderland, the studio’s first television special—which aired on Christmas Day 1950 and featured a fanciful holiday party at the Walt Disney Studios hosted by Walt himself, with appearances by ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummies, Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd.

The success of his first TV special encouraged Walt to make a big commitment to the new medium, and on October 27, 1954, viewers saw the first airing of an anthology program called Disneyland. This wasn’t just a TV program—it was a showcase, specially designed to highlight the great Disney entertainment product, and to acquaint the public with an exciting new project that Walt was cooking up—a destination theme park, also called Disneyland, which had its grand opening in the summer of 1955.

Walt’s adventures into the new medium of television repeatedly caused popular national sensations. One of the great hits spawned by the Disneyland TV show was the tale of a stalwart pioneer named Davy Crockett, and original children’s television saw its greatest progress and innovation with the October 3, 1955, debut of the Mickey Mouse Club. A few years later, in October of 1957, the debut of the Zorro TV series caused a similar, if somewhat smaller, commotion.

Walt hadn’t turned his back on the movies, though. Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Lady and the Tramp continued the Disney tradition of animated storytelling throughout the decade, and rereleases of past classics proved enduringly popular. Disney also introduced audiences to the nature film with the True-Life Adventures documentary series—an idea so revolutionary that Disney ultimately set up its own company to distribute the films.

The year 1954 also saw the debut of the spectacular 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Walt’s first and only true science fiction feature film. As the decade wound down, production was being completed on another ambitious animated feature, Sleeping Beauty, as well as the live-action The Shaggy Dog, the first in a series of a new kind of comedy that would become a staple of the studio for the next two decades.

The Christmas Show Parade debuted in Disneyland on Thanksgiving 1955 and ran through New Year’s Day 1956. The following year, the parade was called Christmas in Many Lands. In

1957, the Candlelight Ceremony and Processional began, and over the years has featured celebrities such as Cary Grant, John Wayne, Dick Van Dyke, and many others narrating a musical retelling of the Christmas story.

On December 19, 1958, From All of Us to All of You, a new television Christmas special, was presented as part of the ABC Walt Disney Presents anthology series. Hosted by Jiminy Cricket, the special combined newly produced animation with clips from classic Disney shorts and feature films, presented to the viewer as “Christmas cards” from the various characters.

It had been a decade of reinvention and rebuilding after the instability and uncertainty of the 1940s. Walt himself was a familiar and beloved presence in households around the world. His stories and characters had earned the admiration and trust of generations. Disney approached the beginning of the 1960s with a renewed strength—creatively, financially, and culturally. A new slogan that began to appear on movie promotional material neatly summarized the status of this revitalized Walt Disney Productions: “Look to the name Walt Disney for the finest in family entertainment.”

Want more? Be sure to check back here for additional excerpts from this amazing collection!