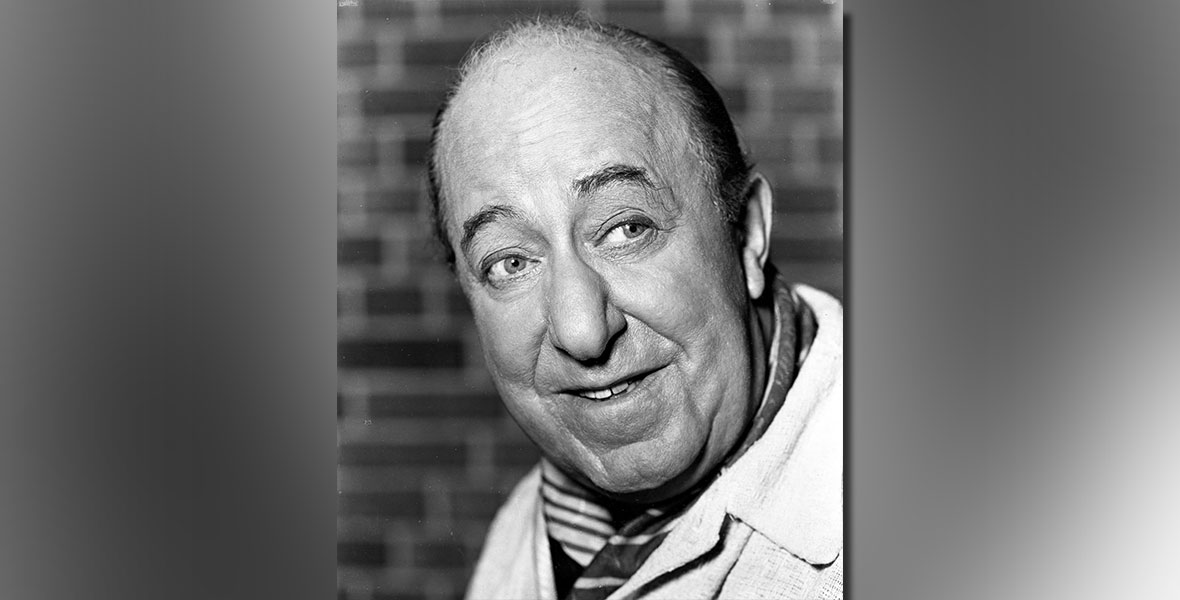

“A comedian,” Ed Wynn once said, “is a man who doesn’t do funny things but who does things funny.” Ed did just that in a long and distinguished career that led from the vaudeville stage to Broadway, radio, television, and the silver screen—a career that defied the maxim that there are no second acts in American life. In the process, he became a familiar face to generations of viewers and found a fan in Walt Disney, who called Ed “our good luck charm.”

Quiet and self-effacing offstage, Ed used oversized shoes, an outrageous wardrobe, and silly hats to create a zany persona, the “Perfect Fool,” known for his squeaky giggle and fluttering hands.

“I don’t care what my calendar age tells people,” he once remarked. “I pay no attention to it.”

Born Isaiah Edwin Leopold in Philadelphia on November 9, 1886, Ed was the son of immigrants. A youthful preoccupation with vaudeville led him to run away from home at age 15 to join the Thurber-Nasher Repertoire Company, but the company soon folded and Ed found himself back home selling hats for his father. Within weeks he hit the road again, headed for Broadway. Dropping the name Leopold out of respect for his father, who disapproved of show business, he split his middle name in two and became “Ed Wynn.”

Success came first alongside fellow comedian Jack Lewis, and then in solo skits including “The Boy With the Funny Hats”—a routine he would reprise decades later on an episode of Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. By age 19, Ed had become a vaudeville headliner.

With his own money, he put on Ed Wynn’s Carnival, which proved a major hit in 1920. Other shows followed, including his most famous role in 1921’s The Perfect Fool. Ed wrote, produced, and starred in the show, which enjoyed a long Broadway run and introduced material that he would revisit for the rest of his career. It was said that Ed used 300 ill-fitting coats and 800 funny hats in his act, alongside a slew of absurd inventions such as an 11-foot pole (for people you wouldn’t touch with a 10-foot pole), a typewriter device for eating corn on the cob, and a piano mounted to a bicycle.

Radio fame came, too, when he starred as Texaco’s The Fire Chief from 1932–35. During both World Wars, Ed contributed by entertaining troops and selling war bonds, and in 1949 he took to the airwaves with The Ed Wynn Show, one of the first televised variety shows. The program earned him an Emmy Award in 1950.

At the encouragement of his son, Keenan, Ed began tackling dramatic roles. The two appeared in the 1956 telecast Requiem for a Heavyweight, which put Ed back in demand as a character actor. Father and son continued to act together in projects both serious and comedic. Ed’s new career reached its zenith when he received a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination for 1959’s The Diary of Anne Frank.

It was with 1951’s Alice in Wonderland that Ed first joined the Disney family, providing the manic voice of the Mad Hatter. Ed returned to his comedic roots as the Toymaker in Disney’s Babes in Toyland (1961); it was a role he said combined his Perfect Fool and Fire Chief characters. During production, the cast and crew threw him a party on the Disney lot to celebrate his 60th year in show business. Son Keenan and grandson Ned, both of whom appeared alongside Ed in The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) and Son of Flubber (1963), were on hand, and Ed was presented a coveted “Mousecar” award to mark the occasion.

Other Disney projects in which Ed appeared include That Darn Cat! (1965), Those Calloways (1965), and The Gnome-Mobile (his final, posthumous, appearance in 1967). He even appeared on Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color series in 1961’s Backstage Party, 1962’s The Golden Horseshoe Revue (wherein he revived many of his classic vaudeville routines), and 1964’s For the Love of Willadean. But it is Mary Poppins (1964) that cemented him in cinematic history as the hilarious, lighter-than-air Uncle Albert who “loved to laugh.”

Ed Wynn passed away on June 19, 1966, in Beverly Hills. Walt Disney, who had wanted to cast Ed for a role in the under-development The Jungle Book, attended his funeral. In an interview before his passing, the vaudevillian said he had warned his son Keenan, who continued to appear in Disney films, that “he won’t inherit much money, but he’ll get a lot of jokes.”