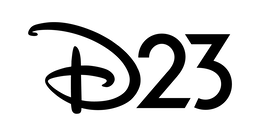

Excerpt #5— Walt Disney Animation Studios—The Archive Series: Walt Disney’s Nine More Old Men—The Flipbooks

By Pete Docter and the staff of the Walt Disney Animation Research Library and with Illustrations by Disney Legend Ub Iwerks; Disney Legend Norman Ferguson; Disney Legend Hamilton Luske; Disney Legend Art Babbitt; Grim Natwick; Disney Legend Vladimir (Bill) Tytla; John Sibley; Hal King; and Disney Legend Fred Moore

It was only nine years between Ub Iwerks’s Plain Crazy (1928) and Grim Natwick’s scene for Snow White (1937), and only eight years more from that full-length animation breakthrough to the release of The Three Caballeros (1945).

In many ways, Ub is the father of Disney animation. Walt was clearly the front man and story mind, but Ub’s sense of design and incredible speed was critical to Walt’s early success.

Born March 24, 1901, as Ubbe Iwwerks, Ub was nineteen and working for a commercial art firm in Kansas City, Missouri, when he met Walt Disney. The two collaborated at Disney’s Laugh-O-grams before its bankruptcy; Disney subsequently asked Iwerks to join him in Hollywood a few years later.

Ub and Walt partnered in creating several early short films. Wilfred Jackson, who later went on to direct at the studio, describes what happened after Ub and Walt talked through a story:

Ub would make a bund of little thumbnail sketches and usually do a sketch for each scene. Each scene cut—close up, long shot. And if it were a long scene, there might be a half dozen sketches of key business in the scene. This was the whole thing, this was the storyboard, these were the layouts, this was what pictured the thing.

Iwerks was also the sole animator of Plane Crazy, the first Mickey Mouse cartoon. Because it was made long before there was a concerted effort to preserve this kind of work, few complete scenes survive from the film. For this book, four missing drawings were re-created: they are 10, 22, 83, and 106.

Though the style of these early film is not subtle in its approach, Ub’s work is beautiful in its simplicity and boldness. Ub’s expressions for Mickey are clear, quirky, and funny. Using just a few lines, Ub flips Mickey head over tail and the horseshoe rotates in space; Iwerks was clearly thinking in three dimensions, not just the two-dimensional graphic shorthand of many other animators of the time.

Unlike later work that was cleaned up and in-betweened by assistants, these drawings are all Ub’s, and he produced them at a breakneck speed. As Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston put it, “Anyone who can turn out six hundred drawings a day, stage a whole picture for both layout and attitude, contribute gags, train the new help, and keep the company car moving is an asset to any studio!”

Iwerks was quiet and focused, determined in his approach. More comfortable doing the work himself, Ub was nevertheless very patient toward new artists. According to Johnston and Thomas, Ub was usually “the only animator who would stop his own work to encourage others. He was gentle and gentlemanly and always absorbed with what he was doing or some idea that was bouncing around in his head.”

By 1930 personal tensions between Iwerks and Disney prompted Ub to try his hand at running his own studio. Despite a contract with MGM to distribute his short films, the Iwerks studio was not successful, and U rejoined Disney in 1940. By this time Ub’s interests in animating had waned, and though he did animate and direct again on occasion (mainly on films for the war effort), his primary focus was in the studio’s Special Process Laboratory. Ub received an Academy Award in 1959 for the design of an optical printer, and then another in 1965 for his work on the traveling matte system.

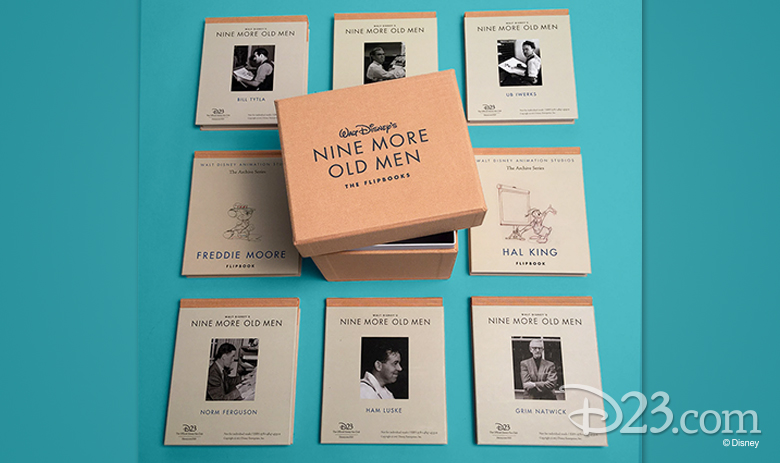

Excerpt #6— Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation

By Mindy Johnson and with a Foreword by June Foray

THE “SILLYS”

The advent of sound opened up new possibilities to the film industry, expanding the roles of dialogue and score. Studios began aligning their slates with musically driven narratives, and for animation, the impact was inevitable. The idea originated with Walt’s new musical director, Carl Stalling: a series of cartoon shorts with music as the focus with action animated to fit the score. The format provided the perfect platform for every facet of the Disney cartoon factory to grow. Story, Animation, Tracing & Opaquing, and Camera—every division of the little studio was called upon to rise to the demands required for this new approach to the medium.

The first of this series was to feature a band of choreographed skeletons. (The idea originated from Stalling’s youth, when he saw an intriguing ad that featured a dancing skeleton.) Though quick and crude in execution, the detail and animation were groundbreaking. Beginning January 1, 1929, Ub Iwerks animated the entire sequence, with some assistance from Les Clark and Wilfred Jackson.

Stalling’s score was infused with Edvard Grieg’s “March of the Dwarfs.” Working in a style of eccentric movement popular in vaudeville and with early films stars of the day, including Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, Iwerks’s masterpiece features a quartet of skeletal figures comically dancing around a graveyard with bone-chilling antics, intricately timed to Stalling’s score.

Matching Iwerks’s style for every grinning ghoul, Mary Tebb, one of the young Tracers and Opaquers at the studio, brought each skeletal frame to celluloid life. Joining the studio in 1927, Tebb single-handedly inked the thousands of cels required for this inaugural short. The new style of this series commanded a higher level of line uniformity to achieve a seamless flow to every dancing vertebra and skull. “How did I do it? I don’t know,” said Tebb. “I was young. I see it now and I’m amazed.”

Tebb later echoed the commitment she felt in her work. “That dedication was the greatest thing in the world—our dedication to Walt and the product, our unquestioning attitude. No one ever said to Walt, ‘Aw[,] that’s too much work, I don’t want to do it.’ Oh no. You’d take it home and spend all night if you had to. Walt had something, that power. It was just his personality, his genius, I guess.”

By late 1929, twenty-five employees were on staff at the small but growing studio. With the continued demand for Mickey Mouse, as well as the range of possibilities he envisioned with the Silly Symphony series, Walt began to institute a division of labor. Iwerks would oversee the Silly Symphonies unit, while director Burt Gillett took charge of the Mickey Mouse cartoons. A separate artist, Carlos Manriquez, was brought in to focus fully on layout, which freed up the Animators to focus on their work. In addition to teaching animation classes in the evening at the studio, Iwerks concentrated on key sketches for others to animate in between.

The women’s roles at the studio expanded as well.

TRACING & OPAQUING

Utilizing more than one piece of celluloid to a frame of film increased the visual sophistication of storytelling. Two to four basic cel levels relayed the overall animated action against the black, white, and gray backgrounds. As an early studio handout clarified, “In the beginning, all action was painted on a single piece, whereas, now the actions are broken down and there are used from two to five pieces of celluloid to each frame of film. The second cel is the main action position or the Key Cel.”

Thus, if only one cel were required, that cel would be shot on the second level with a blank cel on top of it. “Animators make all drawings to be painted for the second cel only,” the memo continued, “regardless of the cel position or exposure sheet, as the second cel gives you the color as it will appear on the scene after it is photographed.”

To ensure clarity of communication for specific details throughout this new production pipeline, an exposure sheet or X-sheet was created for the entire film. Each X-sheet carefully detailed the timing of each individual drawing, movement, and cue (as well as designated the particular cel layer it was to occur on). Miscellaneous notes and directives were also added for each department. This detailed sheet would travel with the artwork as it progressed down the line, charting details, notations, and adjustments each artist might contribute.

With two separate production units functioning at Disney studios, the pipeline of work flowing into Hazel Sewell’s department increased exponentially. More staff was hired to trace and paint, including six women and two men (who worked briefly to meet the demands). Sewell identified the distinct skills required for each discipline and divided her artists into two separate areas based on their talents and abilities. To head her Tracing Department, she assigned Marie Henderson, while Grace Christianson ran the Opaquing Department.

Initially, the Tracers would uniformly outline a character; but with the new Silly Symphony series, the fine art of Inking began to develop. As a studio write-up declared, “Now, all lines have accents and naturally all accents have to fall in the same place for the same character.” The Tracers worked from the Animators’ drawings to transfer the lines to celluloid, translating each character’s form. Once a scene was completed and dried, Tracers sent their scenes over to the Opaquers, or women who painted within the designated areas, ensuring the black, white, and gray paint was thoroughly applied to avoid light leaks once in camera.

The detail demanded by the Silly Symphony series required new approaches. Speed and accuracy were the goal. Lines were simple and functional, but a new level of quality was required for these visual tone poems, from concepts to characters and backgrounds. New shades of white and gray were introduced for opaquing, giving a distinctly different dimension to the Sillys.

To achieve clean lines, painting was introduced to the B-side of the cel. Black, white, and four shades of gray paint lined the shelves of the little studio. When a woman needed paint for her work, she stepped up to the shelves and helped herself. This monochromatic range constituted the entire palette of the early black-and-white Silly Symphonies. Black was the only cel color that did not change when viewed through the nitrate cels, so it could be utilized on any cel level. White, however, and the limited range of grays, required adjustments based on the level of cel they appeared on. Blue or red pencil notations occasionally made by the Animator on the drawings indicated which shade and level each color appeared on. Once a scene was shot and processed for final assemblage, cels were carefully washed and laid flat to dry for another round of use.

Noting the development of the early Silly Symphonies, Roy Disney stated, “They were a stepping-stone, and really Walt had longer pictures in mind. But he had to have better artistry, better results, so those Silly Symphonies were really little vignettes in training and developing for better work later on.”

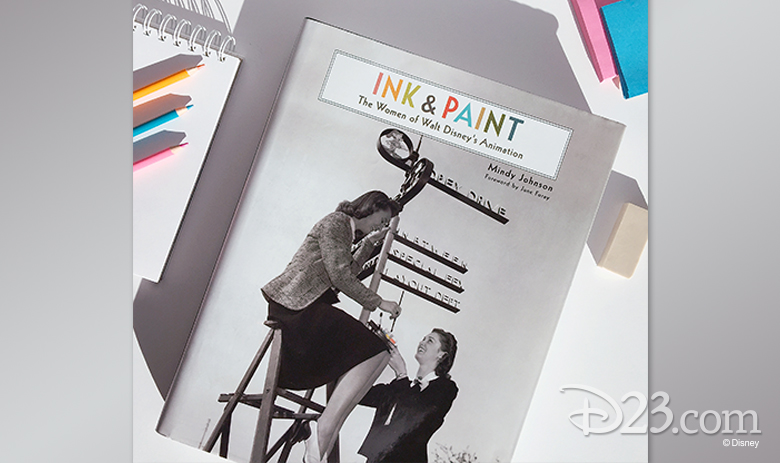

Excerpt #7— Before Ever After: The Lost Lectures of Walt Disney’s Animation Studio

By Don Hahn and Tracey Miller-Zarneke

Artists flocked to the Disney studio in the 1930s looking not only for a job during the Great Depression, but also for a chance to work in the film business with Walt Disney, creator of the enormously popular Mickey Mouse cartoons. Walt himself was gearing up to make his first animated feature—a herculean task, requiring invention, patents, training, and unbounded passion, which fed the nascent art form.

To get his artistic staff to rise to the highest level of performance, Walt quite literally built an inhouse art school. His instructors came from nearby Chouinard School of Art and later featured the best artists, painters, actors, and technicians of that era, who all paraded onto the Disney lot then on Hyperion Avenue to be part of this grand experiment in animated entertainment. . . .

CHOUINARD

“The first thing I did when I got a little money to experiment, I put all my artists back in school.”

—Walt Disney

While the Disney brothers were only dreaming of a cartoon studio, an Irish woman from Montevideo, Minnesota, was already on the path to becoming a key player in their studio’s success story.

She was born Nelbertina Murphy in 1879, later deciding to go by the name Nelbert after being warned by her older brother, Lloyd, that the name Nellie Murphy was already attached to a saucy Chicago showgirl with whom she may not wish to be confused. Nelbert was hungry to study art, so she left home and lied about her age to get into the Pratt Institute in New York, where she focused on painting. There she studied under the guidance of Arthur Wesley Dow, who had been a student at the French Académie Julian and had crossed paths with the likes of Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin during his time in France. Dow impressed Nelbert with two new books he had just finished writing: one was on composition and the other was on arts education, both of which she devoured. It was an invigorating era for painters: Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Mary Cassatt were in their fifties and still painting; and Nelbert was passionate about absorbing it all.

Nelbert’s passion for art never wavered, even in the face of tragic circumstances. When her husband of two years, Horace “Bert” Chouinard, died of cancer at a young age, Nelbert was devastated. She uprooted her life and moved to Southern California for a fresh start. The young widow became part of a vibrant group of landscape painters in Pasadena, a Los Angeles suburb where she taught art at Throop Polytechnic (later known as the California Institute of Technology, or Caltech), Hollywood High School, and eventually the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Art and Design). During her time at Otis, she saw an opportunity in the popular but overcrowded school: a student revolt that prompted Nelbert, then the first art history teacher at Otis, to start her own school.

In 1921, Nelbert opened the Chouinard School of Art in a two-story house on West Eighth Street in downtown Los Angeles. The curriculum she established drew the brightest and best to her school, and in 1929, despite the Depression, Nelbert raised enough money to build a new fifteen-thousand-square-foot campus structure on Grandview Street in Los Angeles. The design of the building fostered communication and was a creative campus so groundbreaking that it appeared in a 1930 edition of Architectural Forum.

While the Chouinard curriculum included graphic arts, illustration, fashion design, painting, sculpture, and pottery, it was Nelbert’s appreciation of drawing as the foundation to art education that caught the attention of a young Walt Disney. It was 1929 and Walt’s newly launched Silly Symphony series would need a higher level of artistry from his studio. He was so motivated by her teaching that he himself would drive his artists to her Friday-night class so they could learn to draw. The studio could not afford the tuition in those early days, so Nelbert generously gave the Disney animators scholarships on a pay-it-back-when-you-can basis so that money was never an obstacle to talent development.

For the young animators, Nelbert’s class in “memory drawing” was a favorite and required study. It was a revolutionary way of learning the human form, not in a stiff, academic way as had been the tradition, but in a kinetic environment where students would study the model for a few minutes and then go into the next room and draw the essence of the action from memory.

The teaching technique was ideal for animators who had to study a performance and quickly sketch the essence of the model on paper without being precious about the drawing. It was fast and bred confidence. Eric Larson recalled being instructed to draw with a pen so that they could only move forward and not erase. Walt was effusive about memory drawing, later fully embracing its practice in-house. “I set up a whole new thing [which is] having its effect now among the artists,” Disney said, borrowing heavily from Chouinard’s approach to teaching. “We think of action. We think of drawing for action. We call it action analysis.”

By 1930, the Chouinard School of Art had twenty-three instructors. Student enrollment rose to 450, with Disney’s animation trainees dominating the night classes. “I remember that you moved into a tremendously exciting atmosphere when you walked into the school,” alumnus artist Millard Sheets recalled. “The students were all business. . . . I think one of the reasons that Chouinard was strong during those years is that Mrs. Chouinard never once backed away from the demand of a tremendous amount of drawing, painting, and design, no matter what the students were going to do. . . . Her whole staff reflected that. It had a great spirit, and they really believed in these things.”

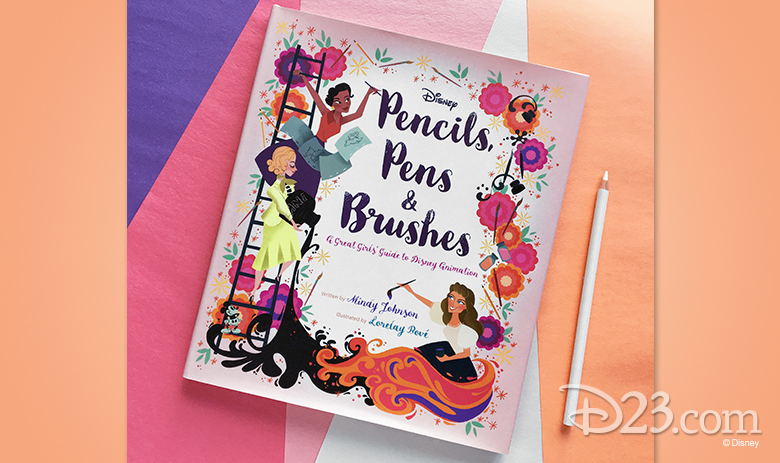

Excerpt #8— Pencils, Pens & Brushes: A Great Girls’ Guide to Disney Animation

By Mindy Johnson and Illustrated by Lorelay Bové

AN ANIMATED DANCE LEGEND

How do you express yourself? When Great Girl Marge Champion danced, she was one of the first to express movement to help Animators understand their subjects.

As a young girl, Marge often assisted her father in his dance studio. Every dancer in Hollywood studied at her father’s studio—even the most popular screen star of the day, Shirley Temple. Marge worked hard and demonstrated dances in each one of her father’s classes. One day, Walt Disney called her father, looking for a dancer who could help his artists understand movement and improve their animation. Marge went with several of her father’s top dancers to audition. And thanks to her hard work, she got the part!

Marge regularly went to Walt Disney’s studio and worked with the artist. She wore a costume and acted out each scene in the film they were creating, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. As a dancer, Marge understood the movements the Animators were looking for—hand gestures, reactions, dancing, quick steps—and she brought these ideas to life. Marge’s action helped the Animators understand what it looked like to call into a wishing well, run through a freighting forest, or joyfully dance as one of the Seven Dwarfs.

After Snow White was a success, Marge returned to Walt Disney’s studio to create the movements for the Blue Fairy from Pinocchio. Her choreography also inspired the artists to animate a chorus of dancing hippos, ostriches, and alligators in Fantasia.

Marge continued to express herself through dance all her life. After her work in animation, she had a successful career dancing with her husband, Gower Champion. They starred in movie musicals, had their own television show, danced on Broadway, and toured across the country in the 1940s and 1950s. Marge and Gower included the talented performer Harry Belafonte in their tours and challenged race barriers by featuring this remarkable African American entertainer.

Together, they toured throughout the segregated South during the mid-1950s and helped bridge differences for their audiences when they saw these three friends sing and perform together.

Performing and breaking barriers remained a large part of Marge’s life. After her husband passed away, Marge continued to perform on Broadway and won an Emmy Award for her choreography on television. After many stage performances, Marge continued dancing and being honored well into her nineties!

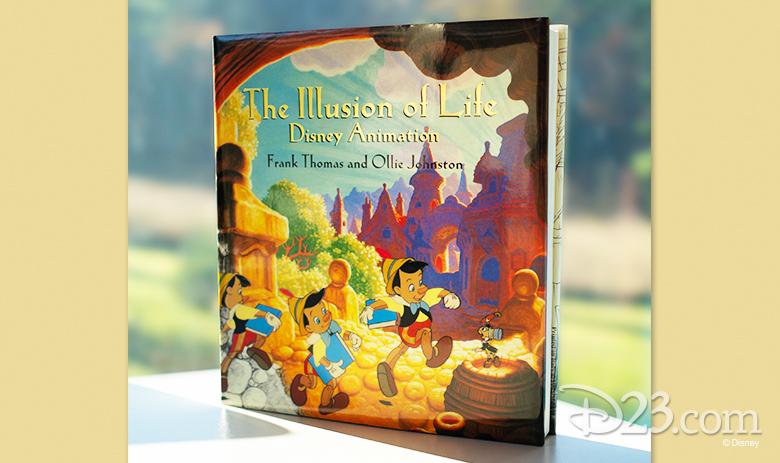

Excerpt #9— The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation

By Disney Legends Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston and with Contributions by Disney Legend Hamilton Luske; V Disney Legend ladimir (Bill) Tytla; Disney Legend Fred Moore; Fred Spencer; Disney Legend Norman Ferguson; and Disney Legend Art Babbitt

THE USE OF LIVE ACTION IN DRAWING HUMANS AND ANIMALS

“This is a very important thing. There are so many people starting in on this, and they might go hay-wire if they don’t know how to use this live action in animating.”

—Walt Disney

Our term “live action” refers here to the filming of actors (or animals) performing scenes planned for cartoon characters before animation begins, as compared to “regular animation,” which develops entirely from an artist’s imagination. The direct use of live action film has been part of the animation industry for years—as an aid to animation, a companion to animation, and even as a replacement for animation. From time to time, almost every studio has fallen back on a strip of live film to perfect a specific action animators were not able to capture. At the Disney studio, filmed action of humans and animals was used in many ways to do many jobs, and it led to some important discoveries. Live action could dominate the animator, or it could teach [them]. It could stifle imagination, or inspire great new ideas. It all depends on how the live action was conceived and shot and use.

In the early 1930s, animators drew from the model regularly, but as the necessity grew for more intricate movement and convincing action in our films, this type of static study quickly became inadequate. We had to know more, and we had to draw better to accomplish what Walt Disney wanted. Some new way had to be found for an artist to study forms in movement, and for this to be useful it had to relate to the work on our drawing boards. Running film at half-speed in our action analysis classes was helpful for a general understanding of weight and thrusts and counter thrusts, but the principles were not directly applicable to animation. Our instructor Don Graham had chosen certain film segments as clear, isolated examples of movements he could use in his lectures, but, while they gave us insight into articulation, they were still essentially classroom exercises.

One day, during a discussion of how Snow White dwarf Dopey should act in a particular situation, someone suggested that his actions might be similar to those of burlesque comedian Eddie Collins. This led to everyone’s going down to the theater to see the exceptional Mr. Collins perform. We invited him to the studio, and a film was shot of his innovative interpretations of Dopey’s reactions—a completely new concept that began to breathe life into the little cartoon character. Dopey had been the “leftover” dwarf, with no particular personality and not even a voice; so, now, to see the possibility of his becoming someone special, and, particularly, someone entertaining, was an exciting moment! And best of all, everything Collins had suggested was on film.

There was nothing in the film that could be copied or used just the way it was, but as source material it was a gold mine. Freddie Moore had the assignment of doing the experimental animation on Dopey, and he ran that Collins film over and over on his Moviola, searching not so much for specifics as for the overall concept of a character. They he sat down at his desk and animated a couple of scenes that fairly sparkled with fresh ideas. Walt turned to the men gathered in the sweatbox and said, “Why don’t we do more of this?”

Immediately other comics were brought in—entertainers from vaudeville, men who had done voices for the other dwarfs; all were put before the camera. No routines were filmed, just miscellaneous activities and expressions that might help delineate a character. Our own storymen who had a special talent for acting were dragged to the sound stage, and animators even photographed each other. As Bill Cottrell said years later, “It all seems so amateurish now—but it was fun! It was fun!” And that spirit of fun and discovery was probably the most important element of that period.

Now we had film that had been shot just for us, directly related to the characters we were drawing, and even though the acting was crude, we all picked up ideas to enrich our scenes. We quickly found that there were two distinctly different ways this film could be used. As resource material, it gave an overall idea of a character, with gestures and attitudes, an idea that could be caricatured. As a model for the figure in movement, it could be studied frame by frame to reveal the intricacies of a living form’s actions.

At that time, the only way of studying live action frame by frame was to trace the film on our rotoscope machine. This was simply a projector converted to focus one image at a time, from below, onto a square of clear glass mounted in a drawing board. When drawing paper was placed over the glass, tracing after tracing could be made, each sheet kept in register by pegs at the bottom of the glass. It was tedious work and time-consuming, but it was the way it had been done for twenty years.

Naturally, Walt changed that situation in a hurry. He had the film processing lab*work out a system of printing each frame of the film onto photographic paper the same size as our drawing paper. These sheets, which we called photostats, were then punched to fit the pegs of an animation desk, and the animator could now study the action by flipping “frames of film” backward and forward, just as he did his drawings. Here could be seen every tiny detail of changing shapes and relationships in the movements. At last, the animators could study all of the mysteries that had intrigued them so long.

*Editor’s note: That’s Ub Iwerks’s Special Process Laboratory!

Want more? Be sure to check back here for additional excerpts from this amazing collection!