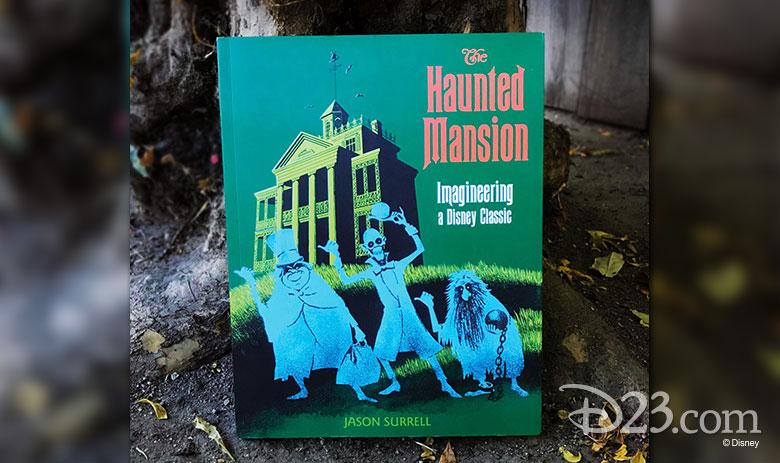

Excerpt #17—The Haunted Mansion: Imagineering a Classic

By Jason Surrell and with Forewords by Disney Legend Marty Sklar and Tom Fitzgerald

THE HAPPIEST PLACE ON EARTH

In 1953, a new home was selected for Disneyland in a 160-acre orange grove at the junction of Harbor Boulevard and the Santa Ana Freeway in Anaheim. The same year, art directors Richard Irvine and Marvin Davis joined [Harper] Goff at WED to collaborate and expand on the design and planning at Disneyland. Walt saw the park as a unique opportunity to tell stories in three dimensions instead of two. The first Imagineers came from the motion-picture industry, and they applied the art and craft of filmmaking to the emerging concept of the theme park. Looking to Disney’s animated features as source material, they storyboarded the new rides and attractions just as they would have a motion picture. Walt even “performed” the rides from start to finish, just as he used to act out the plots of cartoon shorts and features for his artists. A new art form was born.

One of Marvin Davis’s first assignments was to assist with the park’s conceptualization, architectural design, and master planning. In early layouts for Main Street, U.S.A., the land included a small residential area located behind the east side of Main Street. The small, crooked avenue “dead-ended” at a crumbling haunted house on a hill overlooking the turn-of-the-century midwestern town. Harper Goff drew up the concept in a panoramic view entitled “Church, Graveyard, and Haunted House.” The inspirational sketch depicted a ramshackle Victorian on a hill overlooking an overgrown cemetery and a quaint small-town church; it was the very first rendering of a haunted house at Disneyland. The residential area was eventually discarded and replaced by other “lands within a land,” including International Street, Liberty Street, and Edison Square, none of which would make it into the park’s final design.

GO WEST, YOUNG MANSION

Disneyland opened on July 17, 1955, and, after a rocky start, became not only a smash hit but also a cultural institution. It was not long before Walt knew he would have to expand the capacity of The Happiest Place on Earth to allow for ever-increasing crowds.

As part of Disneyland’s expansion, Walt resurrected his Haunted House concept in 1957 and assigned it to Ken Anderson, another top animator who had come over to WED from the studio. Ken had already proved his ability to combine fear with enjoyment as one of the lead designers on the Fantasyland dark rides based on animated features. These included Snow White’s Scary Adventures and Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride.

The old house’s planned site had by now been relocated to the southwest corner of Frontierland on a site already occupied by Magnolia Park, a restful spot filled with shade trees, park benches, and a quaint bandstand, which provided a transition between the Swift Chicken Plantation Restaurant and Adventureland’s Jungle Cruise. Walt planned to transform Magnolia Park and the surrounding area into a New Orleans—themed companion piece for Frontierland.

NEW ORLEANS: QUEEN OF THE DELTA

The Southern influence was nothing new to Frontierland. Aunt Jemima Pancake House (later to become the River Belle Terrace) featured graceful, wrought-iron balconies on its second floor. The Swift Chicken Plantation Restaurant, which sat a lifelike further west on the banks of the Rivers of America, served Southern cuisine and was housed in a plantation-style mansion. Toward the end of the 1950s, Walt decided to make it official by adding a number of new attractions, restaurants, and shops to transform this loose-knit area into a land of its own: New Orleans Square.

Walt went public with New Orleans Square in 1958, when the land first appeared on the Disneyland souvenir map. In addition to the restaurants, guests could expect a wax museum, a Thieves’ Market, and, in the very center, a Haunted House. Walt mentioned the project during an interview with the BBC in London, as he expressed his sympathy for all of the ghosts that had been displaced from their ancestral homes due to the London blitz during World War II and new construction to make way for modern housing. He then announced that he planned to build a sort of retirement home at Disneyland for all of the world’s homeless spirits. “The nature of being a ghost is that they have to perform, and therefore they need an audience,” Walt said. Not even Walt knew it at the time, but the notion of a retirement home for ghosts would become a very important story many years later.

KEN ANDERSON’S FIXER-UPPER

Ken researched the great plantation houses of the Old South, in keeping with the period setting. However, the final design took most of its inspiration from the Shipley-Lydecker House in Baltimore, Maryland, pictured in a book of Victorian-era design found in the Walt Disney Imagineering Research Library. Other design influences likely included Stanton Hall in Natchez, Mississippi, and Evergreen House, a 48-room Baltimore mansion bequeathed to Johns Hopkins University in 1942, and now a public museum.

In 1958, while various story concepts were being considered, Ken drew a rough pencil sketch of a decaying antebellum mansion, complete with an overgrown landscape, sinister-looking trees dripping with Spanish moss, and bats circling in the dark clouds above. Fellow Imagineer Sam McKim took Ken’s sketch and turned it into a painting that would become the attraction’s official portrait. Everyone at WED was thrilled with the Haunted House’s new look—except Walt. Even though the Haunted House had possessed an appropriately menacing appearance since Harper Goff’s very first sketch in 1951, Walt didn’t like the idea of a broken-down, ramshackle plantation house blighting the otherwise pristine look of Disneyland. The rendering led Walt to issue his famous decree: “We’ll take care of the outside and let the ghosts take care of the inside.” Ken wisely decided to table the issue for the time being and focus his attention on the inside of the Mansion. . . .

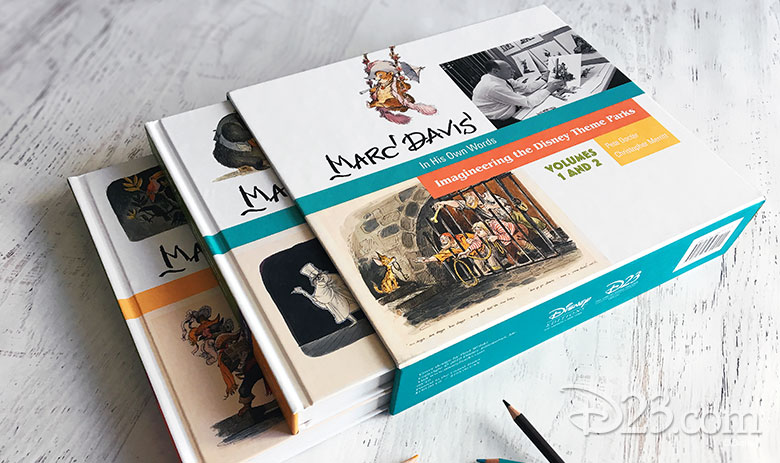

Excerpt #18—Marc Davis in His Own Words: Imagineering the Disney Theme Parks

By Pete Docter and Christopher Merritt and with a Preface by Disney Legend Bob Gurr, a Foreword by Bob Weis, and Illustrations by Disney Legend Marc Davis

“GO TAKE A LOOK”

Marc Davis’s initial work for Disneyland involved mainly improving (or “plussing”) attractions that had already been installed but that Walt wasn’t fully content with for various reasons. Marc’s keen eye for storytelling and his sense of humor would be the hallmarks of his efforts at the Disney parks throughout his career. . . .

SUBMARINE VOYAGE (EARLY 1961 REHAB)

One of the strongest additions to the roster of Disneyland attractions created for the summer 1959 expansion was the Submarine Voyage. Originally featuring art direction by Claude Coats and Bob Sewell, the attraction was loaded with mechanized sea life such as sea turtles, octopuses, a plethora of fish—and a fanciful ending with mermaids and a silly sea serpent. As with Nature’s Wonderland and the Jungle Cruise, Walt decided to upgrade some of the animation and staging. So, in January of 1961, he again asked Marc to “take a look” at what he could do with the new attraction in order to improve it. Many of Marc’s suggestions would be implemented in a rehab during April of the same year.

Marc: “At this one meeting, one of the first things I said was ‘Well, I’ve got an expensive way and a cheap way of doing this.’ And Walt got all the way up from his seat and walked up to the front of the room where I was. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘No. Marc, look, I don’t agree with that. And I do not worry about whether anything is cheap or expensive. We only worry if it’s good. I’ve got a great big building out there full of all kinds of guys who worry about costs and money. You and I just worry about doing a good show.’ And then he said, ‘I have a theory that if it’s good enough, the public will pay you back for it.’ So, since that time I feel that’s my job. If they want to cut something out of it, that’s fine—that’s somebody else’s business. But I try to do the thing the best way I know how. But I think he is absolutely right: when you do something good, and you give the public credit for having brains, then I think the public is going to appreciate what you’ve done for them and pay you back for it. And I think when other people understand that, I think you can do anything. I think that’s the story of the medium at the present time—and probably into the future.”

Joe Potter: “Walt was not a softy. He was a tough, tough guy in the company. He knew what he wanted; people got to know that when he said he wanted something, they’d better do it. Once, I tried to interject something that wasn’t exactly in his train of thought. I told him that something was going to cost a million dollars, and he said, ‘When are you going to learn not to bother with inconsequential things’”

Marc: “There was something about Walt as a personality: when he liked what you were doing, you felt good—you know? You bet on him. He just said to me, ‘Will you do this as long as I pay you?’ I don’t think he ever gave me any choice in doing this!”

Marc: “The most marvelous thing about Walt was that when you spoke to him, you had his total concentration. He was like a child opening up a present at Christmas. You could show him many things . . . but then, if you didn’t have anything else to show, things started to get a little tense. We’re giving you something that is a surprise, and it’s like constantly opening Christmas packages, you know? And that was also a lot like working with Walt, because you had to have a lot of Christmas packages for him. He got very impatient. I found that you didn’t start talking an idea with Walt—you showed him something. And when he could see it, you had his interest. When you didn’t have anything, his first answer was ‘Oh, we don’t want to do that!’ Then you never knew if you could ever try to do it right and show it to him later.”

JUNGLE CRUISE

Walt Disney: “The park is a show, and it must be kept fresh and alive, and kept up to date. Like this year, I rehabbed a lot of things. I went in, and things I put in six years ago, we’ve been just touching up every year. I went in and completely practically rebuilt some of them. It’s the same basic ride, because I found that the ride itself had a basic appeal, but it had to have the excitement. In other words, we plussed this with what we know today against what we knew when we started. I’ve been adding to that as I went along, and I’m going to redo that in about a year. By redoing it, I’ll add a lot of new animals and new areas—and make it more exciting. But it’s still a very good ride.”

The Jungle Cruise opened in 1955 with Disneyland—it was one of the original attractions at the park. Designed by Harper Goff, the attraction was initially extremely popular. In a story related by Randy Bright, Walt was later outside the attraction when, to his dismay, he overheard a guest remark, “We don’t need to go on this ride. We’ve already seen it.” He realized he would need to keep adding new elements to his park, even to attractions he considered finished.

So, Walt talked to Marc Davis. By late 1960, he had sent Marc down to Disneyland to begin to think about new possibilities for the Jungle Cruise.

Marc: “I think Walt asked me to look at this because he knew I would probably give it a pretty good shot. And I think that he liked the kind of entertainment that I was able to do. Walt liked this idea of kind of doing moving tableaux, which he called them, and since you rode by them, the animation would be relatively simple. We had more than you were able to see at any one time, so people would be encouraged to come back and try to catch it on the next time around—this was his reasoning.

“And he always felt that these things were like a three-ring circus. Especially here at Disneyland, as it’s such a tremendous repeat business. If people like the Jungle Cruise, they’ll go on it again. And if the ride is right, they’ll see something they didn’t see before. . . .”

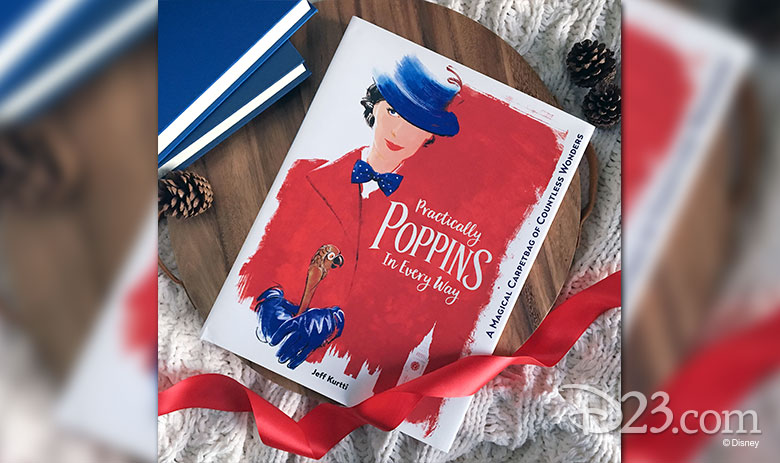

Excerpt #19—Poppins in Every Way: A Magical Carpetbag of Countless Wonders

By Jeff Kurtti and with a Foreword by Thomas Schumacher, an Introduction by Rob Marshall, and Contributions by Craig D. Barton; Brian Sibley; Paula Sigman Lowery; Jim Fanning; Cameron Mackintosh; Fox Carney; Gavin Lee; John Myhre; Marc Shaiman; and Greg Ehrbar

MR. DISNEY OPENS THE DOOR

“One evening in 1939, Walt Disney came home to find his daughter chuckling over a book,” press notes for Mary Poppins at the time of its initial release related. “It was Mary Poppins by P. L. Travers, and this was his first introduction to one of literature’s most beloved and delightful heroines.” Diane Disney Miller recalled the incident exactly, but with one differing detail—the book she was “chuckling over” was a Winnie the Pooh volume by A. A. Milne! “I was only about six in 1939,” Diane recalled.

As with so many creation stories, the meeting of Miss Poppins and Mr. Disney has been told and retold so many times that the facts of the matter have been lost, obscured, or misstated.

Walt’s introduction to Mary Poppins appears to have been in 1934, when Eugene Reynal, of publishing firm Reynal & Hitchcock, sent a copy of a new book to Walt, with the inscription, “To Walt Disney—Not another ‘Mickey’ but I think you should like our Mary.”

After the blockbuster success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the Disney Studio appears to have looked at . . . well, looked at everything. The Studio Library shelves groaned with dozens upon dozens of books—including well-worn and often-borrowed copies of the Travers novels. Walt also purchased film options on dozens of popular children’s and fantasy titles, from Peter Pan to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, to the L. Frank Baum follow-ups to The Wizard of Oz (Walt’s friend, famed producer Samuel Goldwyn, had already snapped up the film rights to the first Oz book).

Not surprisingly, in 1938, the studio looked into the availability of screen rights for Mary Poppins books, but the inquiry was rejected. Meanwhile, some other entertainment luminaries expressed interest in the character and stories. Before Walt’s interest, singer and comedienne Beatrice Little had already begun a decade of ultimately unsuccessful attempts to acquire the right and create a Mary Poppins stage musical.

Then in 1943, the third Poppins book Mary Poppins Opens the Door, was released in the United States. “I was close to eleven years old,” Diane Disney Miller recalled, “and it would have been just my kind of thing.” It appeared to have piqued Walt’s interest again, because in 1944 he dispatched his brother Roy to meet with Travers, who was in New York working for the British Office of War Information. The author remained uninterested in the Disney entreaty. Director Vincente Minnelli and producer Samuel Goldwyn were likewise sent packing by the eccentric author.

According to Disney historian Jim Korkis, “Several months later, Walt phoned [Travers] himself and, by 1946, thought he had an arrangement—but Travers balked at the last minute.”

A breakthrough finally came in 1959, when Walt visited Mrs. Travers in person at her London home. Walt seems to have been able to thoroughly charm her, and at last to explain how the film would be made as a live-action story with only certain fantasy elements being created in animation and special effects. A Travers recalled, “It was as if he were dangling a watch, hypnotically, before the eyes of a child.”

The legalities and negotiations were happily left to the author’s lawyers and the Disney representatives. In an agreement dated June 3, 1960, author and historian Brian Sibley reports, “Travers was not only to receive a $100,000 advance [estimated to be close to $2 million today] against five percent of the film’s gross receipts, but she would also be allowed to write a treatment for the film, have consultation rights on casting and artistic interpretation, and—uniquely—be given script approval. It was something that had never happened before: the Disney studio working with an author on the transition of a book from page to screen. The authors of stories made into Disney films were usually safely dead and beyond consultation and, where they still living, were generally content to leave their books as he thought best.”

Live-action filming of Mary Poppins began at The Walt Disney Studios in May 1963. For everyone involved, it appeared to have been an exceptional professional and personal experience.

“Walt had an infallible gift for spotting talent in people,” Julie Andrews says. “I should add the word ‘decency’ as well. Down to the lowliest gofer in his vast organization, I never met one soul that wasn’t kind, enthusiastic, and generous. The Disney aura touched everyone on the studio lot in those days. . . .”

Disney biographer Bob Thomas, in his authoritative biography Walt Disney: An American Original, reported: “The filming of Mary Poppins, although lengthy, proved to be as smooth and pleasant as had been the making of Dumbo. Some of the sequences were designed for combination live action and cartoon, and Walt instructed Robert Stevenson not to concern himself about the animation; that would be filled in later. ‘Don’t worry,’ Walt said, ‘whatever the action is, my animators will top it.’ He was challenging them, and they knew it.”

Walt made a habit of ‘walking through’ the sets after they had been built, searching for ways to use them. Bill Walsh described a visit by Walt to the Bankses’ living room in search of reaction to the firing of Admiral Boom’s cannon: ‘Walt got vibes off the props. As he walked around the set he said, “How about having the vase falloff and the maid catches it with her toe?” Or, “Let’s have the grand piano roll across the room and the mother catches it as she straightens the picture frame.’”

Dick Van Dyke recalled, “In my opinion, the movie’s unsung hero was the online producer and cowriter, Bill Walsh . . . As with any great film, there’s always someone responsible for the spirit the audience experiences, and as far as I’m concerned, Bill created the lighthearted atmosphere that let us forget we were working and instead feel like we were floating a few feet off the ground through a Hollywood playground, as if we had embarked on a jolly holiday.”

On September 6, 1963, after 105 days of shooting, the live-action production of Mary Poppins wrapped. Elaborate special effects and the complex marriage of animation to live-action scenes, as well as the laborious preparation of a physical prints by Technicolor, would take a further eleven months to complete.

“There have been only two times in my career when I have known that I had a chance to be involved in something special,” Dick Van Dyke says. “The first was The Dick Van Dyke Show, and second was when I read the script for Poppins.”

“In the production of Mary Poppins,” author and historian Christopher Finch wrote, “all of the studio’s resources were pooled to produce a motion picture that probably could not have been made anywhere else.”

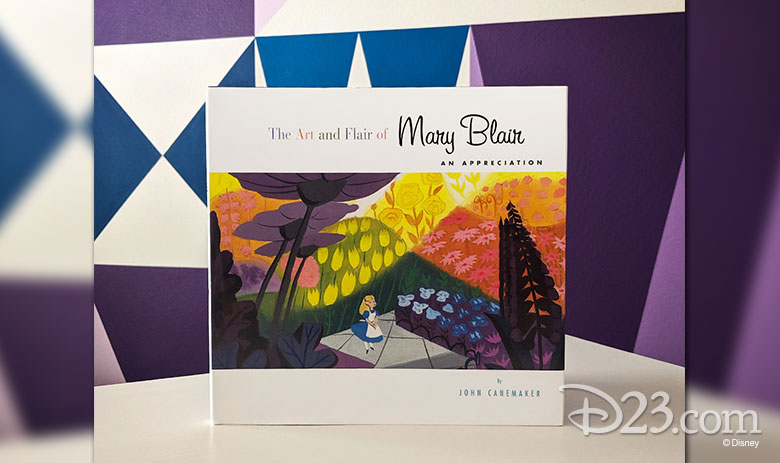

Excerpt #20—The Art and Flair of Mary Blair: An Appreciation

By John Canemaker and Illustrations by Disney Legend Mary Blair

MARY’S WORLD

The 1964 New York World’s Fair arrived a few months after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and a year before America became fully embroiled in Vietnam. It was a last grand utopian dream of international unity and peace, and a paean to progress through corporate technology.

Among the fair’s sponsors were General Electric, Ford, Pepsi-Cola, and the State of Illinois, each of which commissioned large exhibitions from Walt Disney and the artist-technicians he called his “Imagineers.” After months of design and construction in Glendale, California, the exhibits were shipped to the fairgrounds in Queens, New York.

Installation proceeded apace, but the fair’s opening on April 22, 1964, proved to be less than a Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah day.

Although President Lyndon Johnson was the keynote speaker, attendance at the huge exposition was sparse due to cold, rainy weather. There was also a “stall-in” by civil rights demonstrators from the Congress of Racial Equality.

Time magazine dubbed Walt Disney “the fair’s presiding genius,” but on opening day, three of his four exhibitions experienced technical problems. The worst was the Illinois exhibit, which featured a speech by an Audio-Animatronics® Abraham Lincoln. Power surges gave robotic Honest Abe fits so violently unpresidential, Disney temporarily closed the show.

It’s A Small World, a comparatively simple Pepsi-Cola—“sponsored attraction for the United Nations’ Children’s Fund (UNICEF), enjoyed a smoother premiere. In fact, the charming dramatization of the theme, “every child is all children,” became one of the fair’s most memorable exhibits.

In It’s A Small World, boats holding fifteen passengers floated through twenty-six “countries” populated by 250 Audio-Animatronics “toys.” The colorful, stylized settings included onion-shaped Russian domes, Turkish mosques, Japanese arches, a Brazilian carnival, and African grass huts, among other locales; within them diminutive roundheaded dolls dressed in native costumes sang and danced, along with assorted country-appropriate animals such as Belgian geese, an Asian tiger, an Indian cobra, and Chilean penguins.

The puppet’s choreography was synchronized to a simple, repetitious ditty (“It’s a small world after all”); dubbed into twenty-six languages, it stuck in the mind like musical glue.

On a sheltered VIP observation deck above the exhibit, replete with snacks, Pepsi-Cola, and martinis, key Pepsi and Disney personnel and their families celebrated the team who had put together It’s A Small World from scratch in a mere nine months. Participating with quiet pride alongside her husband, Lee, and teenage sons, Donovan and Kevin, was the artist responsible for the overall design and color styling of It’s A Small World: Mary Blair.

Despite overcast skies, the fifty-two-year-old artist wore dark glasses to protect her sensitive green eyes. An ash-blond pageboy hairdo framed the elegant profile of her long face and aquiline nose. She smoked Parliaments, using a white cigarette holder that matched the striking ensemble she herself had designed: a white skirt and jacket with cape, perfectly accented by a black turtleneck sweater. Blair always considered white the most “festive” of colors, and made it the dominant hue in It’s A Small World’s finale.

“This is the most interesting job I’ve ever had,” she later said. “[T]he results are more delightful than anything I’ve tried before.”

The exhibition was, in fact, a three-dimensional culmination of the brilliant art Mary Blair created by the dozens for Disney films. For more than a decade, this unassuming, quiet-spoken woman dominated Disney design.

The stylishness and vibrant color of Disney films in the early 1940s through mid-1950s came primarily from Mary Blair. In her assignments for Disney and other companies, her unique style and distinctive artistic vision pervade every film, children’s book, advertisement, set design, and large-scale mural.

She was born Mary Browne Robinson on October 21, 1911, in McAlester, Oklahoma. The family was poor, the father amiably alcoholic and peripatetic. By age seven, Mary, her parents, and two sisters, including her fraternal twin, had settled in Morgan Hill near San Jose, California.

Her artistic gift manifested itself early. At twenty she won a scholarship to the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles. There she aspired to become an illustrator like her favorite teacher, Pruett Carter (1891–1955).

Her marriage in 1934 to another scholarship student, Lee Blair (1911–1993), led to an interest in fine-art painting. During the Depression, the Blairs became important participants in the regionalist California school of watercolorists. The couple exhibited in galleries nationwide, but reluctantly supported themselves working at several Hollywood cartoon studios.

At Disney’s, Mary Blair first gained attention with exciting conceptual paintings for the South American features Saludos Amigos (1943) and The Three Caballeros (1945); she suggested color and styling for postwar omnibus (or “package”) features Make Mine Music (1946), Melody Time (1948), and The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949); designed sets and costumes for the combination animation-with-live-action films Song of the South (1946) and So Dear to My Heart (1949); and created color concepts for the full-length animated fairy tales Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953), plus the 1952 shorts Susie the Little Blue Coupe and The Little House.

Small gouache-and-watercolor paintings flowed from Blair’s brush suggesting possibilities for staging actions; the mood and emotional content of scenes; and color and design ideas for characters, props, costumes, and backgrounds. She described her job as “working with the writers and helping to create the ideas of the picture graphically right from . . . its basic beginning.” Her inventiveness proved a constant inspiration to story, background, layout, and animation crews.

Walt Disney loved her art and championed it at the studio. This struck some as odd, for Blair’s stylization is the polar opposite of the representational “illusion of life” associated with Disney animated films. Her work is flat, antirealist, and childlike (faux naïf), painted with a wildly unrealistic color palette.

Her work evokes the soft abstraction of Milton Avery and Marguerite Zorach rather than the homely representational style of Norman Rockwell and Gustaf Tenggren, who also influenced Disney design. She is more interested in playing with color and form than developing personalities. Her figures tend to be small and to float surrealistically, as part of the overall textures, interlocking shapes, and patterns in nearly abstract compositional structures.

To Disney, this was a form of modernism that he was comfortable with. . . .

Want more? Be sure to check back here for additional excerpts from this amazing collection!