By Alexander Rannie

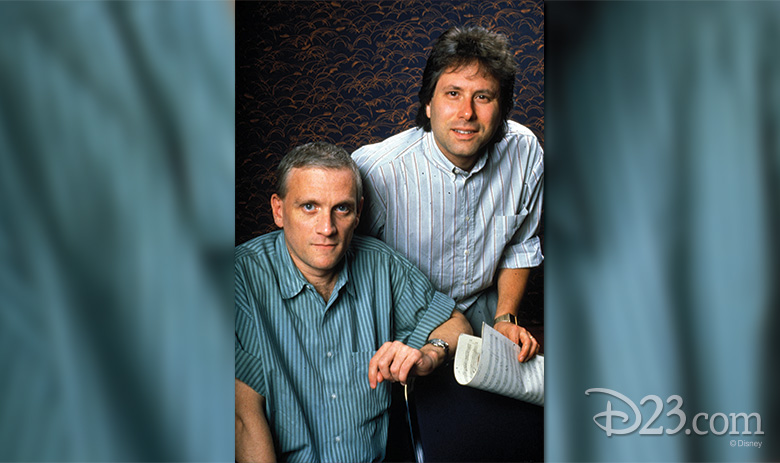

In hindsight it seems a no-brainer that Beauty and the Beast, Disney’s 30th animated feature, would have begun life as a musical. But as many folks know, this wasn’t the case. Songwriters Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, fresh off their success with The Little Mermaid, immediately began working on songs for Aladdin. Beauty and the Beast was being developed for Disney by a British animation director and was intended to be a straight, non-musical feature. When, after viewing early story reels (filmed storyboard drawings, with accompanying temporary dialog (scratch tracks) and music (temp tracks)), the powers-that-be decided to start anew with a different director, and Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenberg approached composer Ashman and lyricist Menken and asked them to become involved in the project. They agreed, setting aside work on Aladdin, with Ashman taking on the additional role of executive producer.

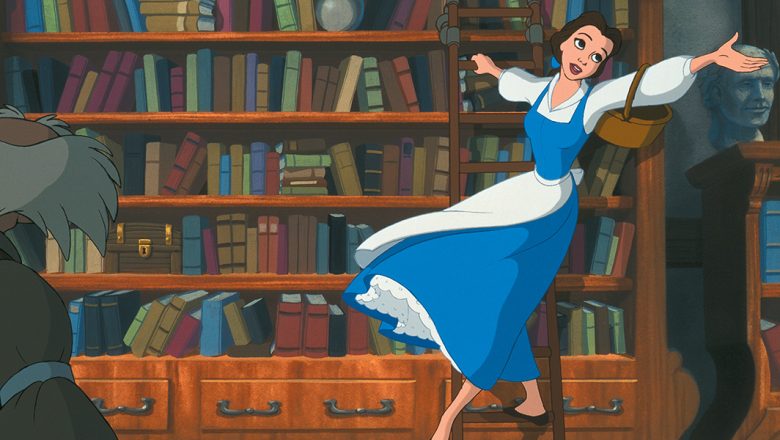

In Ashman’s notebooks, now housed at the Library of Congress, he outlined brief character studies for each of Beauty’s dramatis personae under the heading “The Important Stuff.” In particular his assessment of the relationship between the Beast (“The King”/”Yul Brynner”) and Belle (“[She] tames him. Teaches him table-manners. To dress. To love music. To dance. TO READ.”) provides the framework upon which the story and songs would be placed. As a lyricist, Ashman knew that he had to understand his characters backwards and forwards before he could begin to put words in their mouths.

Working quickly, Ashman and Menken recorded song demos with Howard performing the majority of the vocals while Alan played piano, singing along from the keyboard when a second voice was required. It was principally Ashman who thought out what action was to take place during a song. Just as a choreographer tells a dancer where and when to move, Ashman, working with Menken, figured out when and where a character would speak or sing. The opening number, “Belle,” amply demonstrates this plotting of action. Within a single song we’re introduced to Belle and hear her sing to herself of her wishes (“There must be more than this provincial life…”), we hear her talk to the baker and the bookseller, we hear what the townspeople think of Belle (“She’s different from the rest of us…”), and we’re introduced to Gaston and LeFou and hear the former sing of his desire for Belle (“Right from the moment when I met her, saw her…”). It’s an incredibly compact four minutes of entertaining exposition—and all set to music!

To facilitate the collaboration between the songwriters and artists in further plotting out, or “routining,” the action of the songs, producer Don Hahn, directors Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, story supervisor Roger Allers, several story artists, including Brenda Chapman, Chris Sanders, Kevin Lima, and Sue Nichols, along with art director Brian McEntee, frequently made their way to Fishkill, New York (near to Howard Ashman’s home), or a Disney boardroom in New York City, where they would work out every bar of music in a song and its corresponding on-screen action. Producer Hahn recalls a particular moment toward the end of “Belle” where Roger Allers wanted more back and forth among the townspeople. So, with Menken at an electric piano, and Ashman riding herd, phrases and suggestions of action were tossed back and forth as to what people could sing. The resulting verbal and musical counterpoint as Gaston follows Belle through the crowd (“Bonjour/Pardon!/Good day/Mais oui!/You call this bacon?…”) allowed for a great deal of visual choreography, and a building of energy toward a big finish, while staying focused on the story point of the song.

One tune that didn’t require as much elaborate routining was the title song, “Beauty and the Beast.” When it became readily apparent that the ballroom sequence was going to be something special, Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenberg asked Howard Ashman and Alan Menken if the song “Beauty and the Beast” could be extended. Howard replied, “no,” as he’d used up every rhyme for Beast except for “priest, yeast, creased, and greased.”

As songs were completed and routined, they were arranged by Alan Menken and Danny Troob, orchestrated by Troob, and then recorded under the baton of conductor David Friedman (who also contributed vocal arrangements). Sessions took place in the now long-gone, and much missed, B.M.G. Recordings Studios on West 44th Street in New York City. As with Mermaid, Ashman insisted that the singers be allowed to perform the songs at the same time the orchestra was playing—not as an overdub to a pre-recorded track. The vitality of the live orchestra, Ashman argued, would energize the singers, almost as if they were giving a performance before a live audience.

Producer Don Hahn, and film editor John Carnochan, were eager to have the recorded songs in hand so that storyreels could be put together and scenes handed out to animators. Beauty’s schedule was already a truncated one—down to two years from the usual four—due to the false-start of the non-musical version. And having final recordings of songs meant that no further changes could be made to their respective sequences.

One song that didn’t make it into the original version of the film was “Human Again,” wherein the household objects sing of their imminent hope to be returned to their human forms. It was replaced by “Something There,” in which Belle and the Beast begin to grow fonder of one another. “Something There” is the only song that was recorded in Los Angeles and is also the only time we get to hear the Beast sing.

Once the entire film was edited and locked—meaning, ostensibly, no further changes would be made—the directors, Wise and Trousdale, and producer, Don Hahn, met with composer Alan Menken in a screening room for the music spotting session. It’s at this point that decisions are made as to where musical cues begin and end, and what the nature of each cue should be. For comedic scenes the composer may be asked to “Mickey Mouse” the action. “‘Mickey Mousing’,” in the words of author and critic Mindy Aloff, “does indeed refer to a kind of musical illustration, in which some aspect of the music—the melody, the rhythm, the instrumentation—seems to duplicate (and therefore to reinforce or amplify) an action we see on-screen.” So when a character hops up a staircase, the music hops as well. When a character slides down a bannister, the music descends as well. And so on. For quieter scenes the underscore may be called upon to illuminate the emotional underpinning of a character’s state of mind or mood, rather than specifically mirror on-screen action

In some cues a tune previously heard in the film is reprised, albeit without lyrics. For example, during the battle for the castle (where the household objects defend their home from the mob), the melody for “Be Our Guest”—previously associated with the household objects—accompanies the chaos. And when Belle and the Beast reunite during the climactic battle on the rooftop of the castle, strains of “Something There” can be heard as they extend their arms toward each other.

To underscore the death of the Beast, Menken originally wrote a deeply moving, but very sad cue. (With the recent passing of Alan’s writing partner, executive producer and lyricist Howard Ashman, it would be hard to imagine a more difficult task than writing music for the death of the Beast.) But Disney executive Jeffrey Katzenberg saw something different in the scene. As producer Don Hahn recalled, Jeffrey felt that the cue should play the love between Belle and the Beast, not his death. “The heart [of the scene] is in the love.” Menken rewrote the cue, which was quickly recorded in New York. (Though most of the underscore was recorded in Los Angeles, this last cue was recorded back east in the same studio where the songs had been recorded earlier.) Editor John Carnochan immediately left the recording session, tape in hand, and took a red-eye flight back to Los Angeles so that the music could be speedily incorporated into the already in-progress final mixing sessions.

As with The Little Mermaid, Ashman and Menken took a cue from earlier Disney animated features, and concluded Beauty and the Beast with an off-screen chorus reprising a musical moment of import—in the case of Beauty, the last few lines of the title song:

Certain as the sun

Rising in the east

Tale as old as time

Song as old as rhyme

Beauty and the Beast

At the heart of Beauty and the Beast are the love and self-sacrifice that are finally expressed by the two lead characters. Ashman and Menken’s songs—brought to life by dozens of talented arrangers, orchestrators, and musicians—inspired Disney artists to new heights. Just as with Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs some 54 years earlier, audiences forgot they were watching a cartoon and simply fell in love with Belle and the Beast.

Special thanks to Don Hahn and John Carnochan.